In his latest project and soon-to-be book, George Georgiou finds anonymity and intimacy along the roadside of American parades.

This article was originally published in issue #7883 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

At the beginning of 2016, the United States was gearing up for one of the most divisive elections in its history. Donald Trump had not yet been selected as the Republican candidate, but the cycle was already in full swing. At the same time, George Georgiou was travelling along the West Coast, shooting the first pictures of his new project, the idea of which had been brewing quietly for several years, and which would eventually become In the Company of Strangers: Americans Parade.

“Is it possible to make an interesting body of work in the US, knowing what’s been before?” Georgiou asks. Making work in the States had been an aspiration for him since his student days at London’s Royal Polytechnic Institution. America, with its incomparably rich photographic precedent, presented a challenge common to all aspiring photographers brought up admiring the work of Evans and Adams and Frank: ‘Is there something I can find here? Is there something I can see? Is there a commentary I want to make, is there something I can understand?’ The route to Americans Parade was, however, circuitous.

In 2011, Georgiou was part of the New Photography show at MoMA in New York, the same year his partner, Vanessa Winship, won the Henri Cartier-Bresson Award, funding her proposal for a new body of work in the United States. It was their moment; but Georgiou stopped shooting. “I felt that Vanessa needed to kind of make her own way. She had a deadline. I didn’t have a deadline,” he explains.

They travelled the length and breadth of the country together, Georgiou assisting her in making the work that eventually became She Dances on Jackson. But despite putting the camera down himself, ideas were beginning to percolate and impressions beginning to form. “I stopped shooting, but I didn’t stop looking and trying to find out what was interesting to me.” Four years after the beginning of Winship’s project, Georgiou began his own American work in earnest.

“At the beginning of 2016, I thought, right: it’s now or never. I’ve got to go out and start this work or forget about it,” Georgiou recalls. He flew to LA to follow the thread of a project he’d been ruminating on – about “the politics of the road, how the road has shaped America, how it’s created a lot of separation and segregation” – leading him to a Martin Luther King Day parade, which he photographed.

A couple of days later in Long Beach, at the second parade he went to, the aesthetic of the work, his whole approach, suddenly emerged fully formed. “I parked the car, got to the parade and instantly started shooting like this,” he remembers. The pulled-back, all-encompassing, teeming vistas that now populate his eventual project were all he shot that day, with not a single false start, not a single frame that deviated from the form. “I just instinctively knew what I was going to do,” he says.

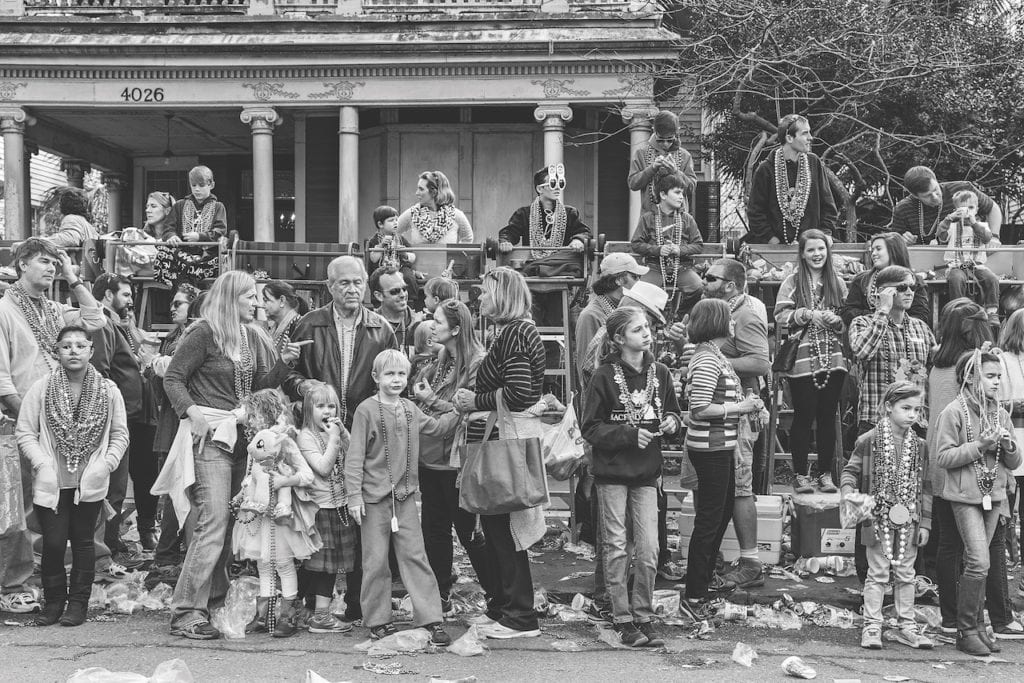

American Parade, the resulting incarnation, is a series of tableaux. The viewpoint is at a remove, taking in a sweeping section of a crowd. At times – at the larger parades – it is held back behind barriers, at times just showing a few figures or a few family groupings looking around on an American sidewalk, presumably taking in the flourishes and celebrations of a parade that occurs out of shot.

Georgiou photographed at Mardi Gras, Fourth of July, St Patrick’s Day, and Martin Luther King Day celebrations. He also photographed on enormous metropolitan boulevards closed down for the festivities, and in tiny communities in small-town America. The context is constant, but the particulars change. With Georgiou, we are witness to an act of witnessing, the detritus of a public celebration gathering in the trash at people’s feet.

At times – at the larger parades – it is held back behind barriers, at times just showing a few figures or a few family groupings looking around on an American sidewalk, presumably taking in the flourishes and celebrations of a parade that occurs out of shot. Georgiou photographed at Mardi Gras, Fourth of July, St Patrick’s Day, and Martin Luther King Day celebrations. He also photographed on enormous metropolitan boulevards closed down for the festivities, and in tiny communities in small-town America. The context is constant, but the particulars change. With Georgiou, we are witness to an act of witnessing, the detritus of a public celebration gathering in the trash at people’s feet.

Georgiou photographed at Mardi Gras, Fourth of July, St Patrick’s Day, and Martin Luther King Day celebrations. He also photographed on enormous metropolitan boulevards closed down for the festivities, and in tiny communities in small-town America. The context is constant, but the particulars change. With Georgiou, we are witness to an act of witnessing, the detritus of a public celebration gathering in the trash at people’s feet.

At times – at the larger parades – it is held back behind barriers, at times just showing a few figures or a few family groupings looking around on an American sidewalk, presumably taking in the flourishes and celebrations of a parade that occurs out of shot. Georgiou photographed at Mardi Gras, Fourth of July, St Patrick’s Day, and Martin Luther King Day celebrations. He also photographed on enormous metropolitan boulevards closed down for the festivities, and in tiny communities in small-town America. The context is constant, but the particulars change. With Georgiou, we are witness to an act of witnessing, the detritus of a public celebration gathering in the trash at people’s feet.

In Algiers, the beads are far fewer, and there are no high chairs, just a sea of African-American faces, blank sky and telephone wires behind them. Like a traditional portrait, each one tells a story of the environment and the people in it, the economic and racial context of the parade. Then again, the anonymity and sheer volume of the different faces blur into a kind of abstract familiarity; in each picture we find ourselves searching, inadvertently, for somebody we know. “It’s kind of like we’re looking at ourselves. We could be in these pictures,” the photographer observes. Georgiou is ever-conscious of the sense of recognition and connection that is inherent to the work, the way that even a crowd, when repeatedly portrayed, can come to feel personal.

“When you’re making a portrait, there’s a performance to an extent. It’s a stage that’s created between the two people.”

Throughout the project, Georgiou maintained a near-invisible presence. There are almost no images in which any of the crowd look in the direction of the camera, their attention elsewhere: on family members, or their phones, or the commotion around them. Even in the case of small groupings of just a few people, his subjects remain impassive, unbothered by the documentarian’s presence. Georgiou credits his absence from the work to his blending into the background, both due to being surrounded by a spectacle more absorbing than him, and to his unassuming mien: “I think if there’s any advantages to getting older, it’s that you become less threatening to people,” he laughs.

In this way, Georgiou was able to access a surprising kind of intimacy with his multiple subjects: the intimacy of unguarded self- presentation, the purity of revelation that emanates from a person who is unaware of being looked at. This way of engaging is in stark contrast to the more formalised work of a directed portrait sitting. “When you’re making a portrait, there’s a performance to an extent,” Georgiou explains. “It’s a stage that’s created between the two people. I don’t know who influences that stage the most, I don’t know who reveals the most. If you look at the portrait, is it revealing more about the photographer, or is it revealing more about the subject?”

By contrast, the images in Americans Parade are guileless, without motive. Georgiou withholds judgement: he seems to be as invisible to the viewers of his images as he is to his subjects. “That’s the beauty of it,” he says, when I ask about the work’s impression of motivelessness. “It has that feeling of detachment.” In any one frame, there was so much of which Georgiou was unaware, and this element of chance is important to the photographer, allowing him to operate at a remove, for the photograph to create itself and to construct its own narrative.

The conclusions can be drawn from any one image and made by the viewer rather than being proffered by the didactic hand of the artist. “That’s the good thing about photography,” he iterates. “I know that things are not black-and-white. I know they’re complicated, everything’s complex. And I like to understand the world with that nuance.” This is particularly true of Americans Parade.

While Georgiou was shooting the project, Trump was elected, and North America’s sociocultural landscape shifted seismically. But much of the approach for Georgiou’s work came to him during his travels with Winship – that period when he wasn’t working at all, and when Trump was still a distant spectre on the horizon. “That time allowed me to deal with my own anger with the States,” he says. “It’s very easy to attack the States, but then I don’t think you necessarily make anything interesting. You have to have some kind of empathy.”

In the eventual project, both empathy and anger are barely visible, veiled behind the mass of the crowds. The scenes play out with their own logic, Georgiou their witness, and us their audience, a crowd witnessing a crowd. Georgiou’s next projects will undoubtedly continue with some kind of social commentary, though for the moment he is in no rush, enjoying the process of thinking, of observing. “I like the theatre of life,” he says.