Amsterdam — Agency is part of a wider series, The Docklands Project, which documents the transition of former harbour areas in different cities, particularly at a time when such locations are highly sought after. The project also explores Red Hook in Brooklyn and waterfront developments across London.

The first time Langendijk visited the ADM community he was introduced by someone he knew. “I stayed for almost two weeks during winter because they were away and I could stay in their caravan,” he says. “By being present and engaging with their way of life, I broke down a few barriers. And then, a couple of years later when I returned, people still recalled me being there a few years earlier.”

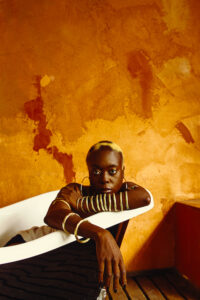

Familiarity was not the only factor that enabled Langendijk to make the portraits he did. Finding common ground with his subjects and taking the time to speak with them allowed him to create a bond. “For a brief moment, you just connect with somebody,” he says. “I think that is the beauty of portrait photography.” By the end of the project, Langendijk was able to come and go as he wished.