This article was published in issue #7890 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

“The winter of 2015 in Connecticut was particularly terrible,” recalls Eli Durst, “and I was struggling to find people to photograph. My photographs seemed static, both in the way they were made and in the lack of life they depicted.” Accustomed to photographing suburban living, in colour and on large format, the one-time assistant to Joel Meyerowitz decided to move indoors. “Church basements seemed like the perfect jumping-off point because they embody a certain paradox,” he says.

The basements are host to a panoply of differing group activities, from Boy Scout meetings to psychic readings to corporate team building exercises. The photographer describes them as, “A quintessentially American space that is simultaneously completely mundane and generic, but also deeply charged psychologically as a point of ideological production.” These scenes are presented together without caption or explanation in his first book, The Community, published by Mörel Books, forming an offbeat narrative of sign and symbol wrested from their original context.

The change of subject matter – moving inside, underground, to fixed, windowless spaces and fluorescent lighting – required a radical change of approach. “Given the lack of available light and my desire to capture movement and activity, I began to use strobes to freeze motion,” Durst explains. Shooting digital images in black-and-white, he soon found a novel way of seeing and approaching his subject matter.

Though Durst has always had an eye for the off-kilter, the prevailing effect of the images in The Community is one of particularly unbridled strangeness. The pictures are strange not only in their central subject matter, but in the way that they continually prick you with additional oddness – mundane details that seem unresolved, or provoke further questions that go unanswered.

In one, a man holds a card above a woman’s face as she lies on a table, his other arm held limply in a cast. Often the images melt into one another, finding a rhyme in the one that follows. One picture, of a man wearing a tousled wig, is mirrored overleaf by that of a little boy, his longish hair wet, fixed into a shape not unlike the wig from the preceding page. “I was intrigued by the figurative space that exists between the photographs,” says Durst, “the moment when one activity bleeds into another.” The images seem to carry their own peculiar vernacular, a kind of dream logic that opens up between them that is difficult to parse beyond the immediacy of the visual.

At a surface level, the images document different constellations of people engaged in a “search for purpose or meaning” (as Durst describes in the project introduction). After all, these are citizens taking part in voluntary, unpaid activities, outside their working hours, and away from their families. The benefits they receive within this bland environment are personal, or spiritual. “Many need a secular sense of purpose or identity,” he explains, and this comes from shared activity, or a kind of adult play dislocated from the bounds of real life and responsibility.

Despite the often secular context of these activities, however, the images can cleave to Christian iconography, perhaps unsurprisingly given their location. The opening image depicts a perfect apple, centred on a table, gleaming and inviting. In another, a man holds a note to his head, declaring himself “a white dove”. One image shows the figurines of a nativity scene. Christian principles are writ through American culture, and Durst underscores a traditionalism that these groups find themselves near, even if not actively participating in it.

The photographs were in fact made during a very particular time in America’s history: the years between 2015 and 2018 that saw the end of Obama’s presidency and the beginning of Trump’s election. The sense of community and shared purpose documented within the photographs are in stark contrast to the divisions that have flared up across this period. “As hyper-partisan and divided as the country seems,” he says, “I think there’s something optimistic in the premise of the photographs: people coming together in search of some form of communal self-improvement or self-realisation”.

The political context of the time is largely absent from the work, however. In fact, one of the most singular features of the project at large is its purposeful dislocation from the contemporary. The basement spaces themselves are anonymous, their furnishings basic, inoffensive abstract pictures of sunrises on the wall. “While there are some hints of contemporary technology, most images are temporally pretty ambiguous,” Durst agrees.

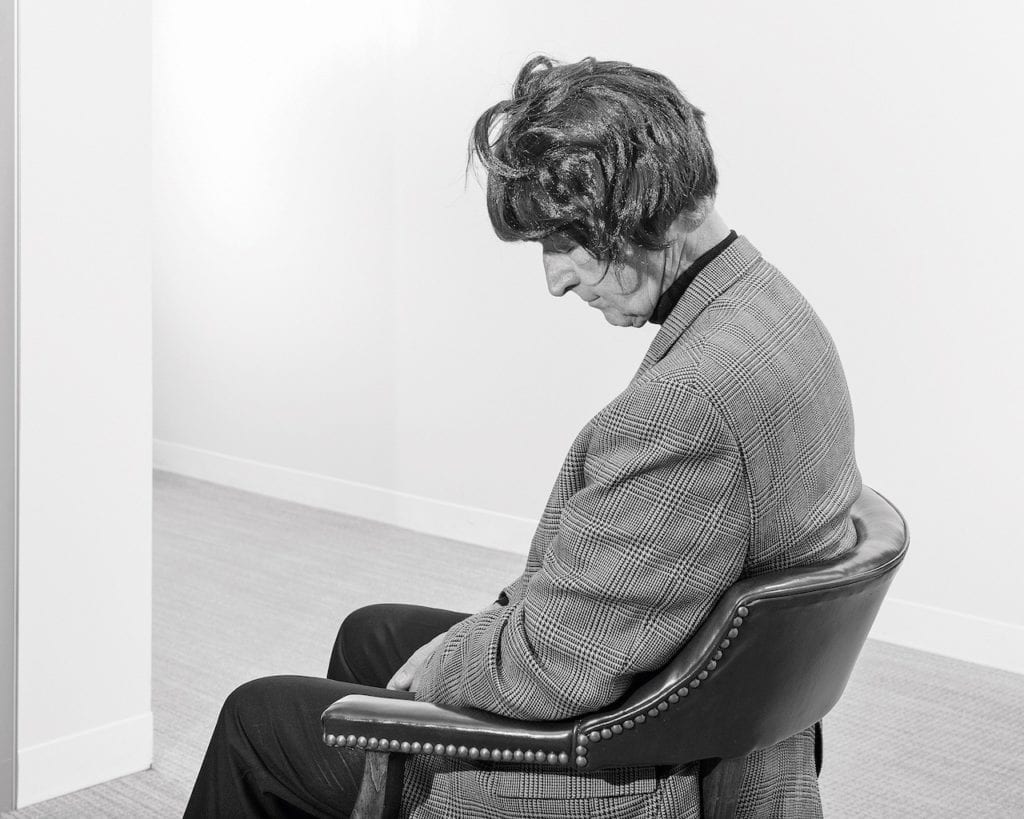

Indeed, when these hints are included, they’re often muddled or muddling. “I hope the images feel as connected to previous decades as to our own,” he suggests. His creation of this temporal ambiguity carries through even to the people in the photographs. They are shown in such a way that none seems particular, no idiosyncratic feature or expression closely attended to; diverse at the level of age, gender and ethnicity, Durst’s subjects seem as anonymous, as outside time, as the decor that surrounds them.

Even moving, their gestures seem somehow inanimate and unnatural, frozen out of believability. The seemingly bizarre nature of the activities these people are engaged in, as well as Durst’s careful editing, framing, and use of strobes, all seem to have stoppered the meaning from their motion. They seem like actors in service of the internal narrative of the photographs, whose own understanding is purposefully unclear.

Throughout his career, Durst has been inspired by documentary film-makers such as Errol Morris and Werner Herzog, particularly in their questioning of the boundary between truth and fiction, their calling attention to the manipulation inherent to any creative narrativising. This questioning is alive in his own work too.

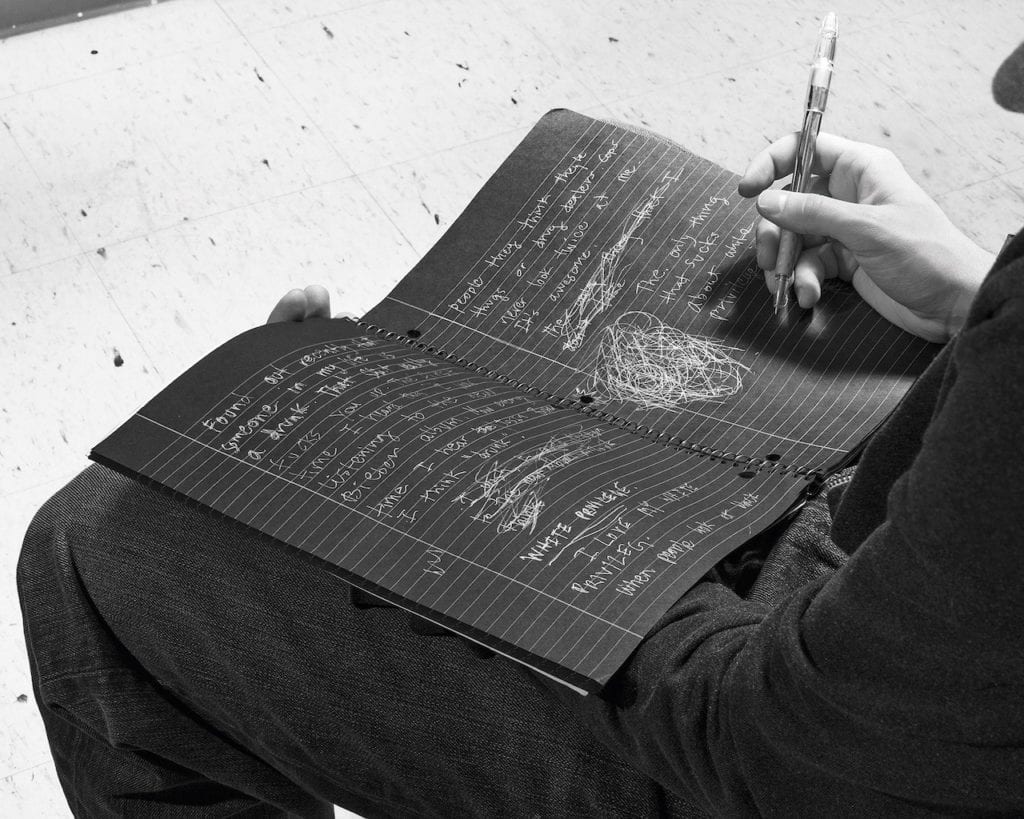

“I believe that every photograph is, in some sense, a fiction, and that simply the presence of a photographer exerts a sort of gravitational pull on the people being photographed,” he says. The photographer was unable to be a fly-on-the-wall, but nor did he want to. “Some of the photographs were made from pure observation, but I also intervened constantly, asking people to redo or reimagine certain things or moving them around to create more compelling photographs,” he describes, hence the wooden quality of some of the gestures, their incongruity suggesting that these images cannot be read using usual codes of comprehension. “I’m interested in using the language of documentary, but only in so far as I can subvert or contort it,” he says.

At a deeper level, then, in their jumble of signifiers, their dizzying internal logic, the images speak to the circularity of any search for meaning, how ultimately difficult this search is to resolve. “It’s human and absolutely necessary to seek answers to existential questions about death and morality and purpose. At the same time, it’s an impossible task,” says Durst. “I think this paradox is reflected in the photographic endeavour itself, attempting to represent one’s interiority – desire, grief, longing, joy – while only depicting the surface of things.”

Durst’s images encourage us away from the appealingly neat and definitive views encouraged by mainstream media, and the contemporary context that requires us to constantly announce ourselves and delimit our values. In their lack of easy understanding, the photographs open a space of nuance in a particular time where everything seems to need to be made digestible. The Community can be read as a kind of refusal, an alternative reality where gesture does not have to be significant, but can simply reflect a different gesture that came before, can point to nothing but a loaf of bread.

The Community by Eli Durst is published by Mörel Books.

—