Alfredo Jaar has never been a studio artist; “I respond to the context in which I live,” he says. The artist devours the daily news, dividing current affairs into categories, which provides him with an overview of events worldwide. Jaar observes as situations and conflicts develop, but there comes a certain point at which he feels compelled to act, and this was the case with Rwanda.

The Rwandan genocide began on 06 April 1994 following the gunning down of an aeroplane transporting the Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana and the Hutu president of Burundi, Cyprien Ntaryamira, near Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Tensions between Rwanda’s Hutu ethnic majority and Tutsi minority had intensified during the end of the 20th century. This was the turning point. The incident sparked a nationwide massacre: Over 100 days, the Hutus, encouraged by local officials and the Hutu Power government, collectively murdered an estimated one million people – the majority were Tutsi along with moderate Hutus.

“I started following the genocide from April and I was shocked by the indifference of the world community,” recounts Jaar when I meet him at his exhibition 25 Years Later on show at Goodman Gallery, London, to mark the 25th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. The US, led by President Bill Clinton, refused to involve itself in the conflict. It withdrew the majority of UN peacekeepers and shunned the term “genocide” to avoid having to intervene.

“I am trying to do something that is impossible to do. How do you convey the magnitude of this event? You do not. You barely scratch the surface”

The international media was similarly indifferent. The New York Times took over a month to report on Rwanda, and, even then, the article was relegated to the sixth page. The piece begins: “As many as 10,000 bodies from Rwanda’s massacres have washed down the Kagera River into Lake Victoria in Uganda in the last few weeks, creating an acute health hazard, a senior Ugandan official says.” It was the apathy of the media, politicians, and society at large that incited Jaar to travel to the country in the aftermath of the brutal unrest. “I had to go to express my solidarity and to witness,” he says.

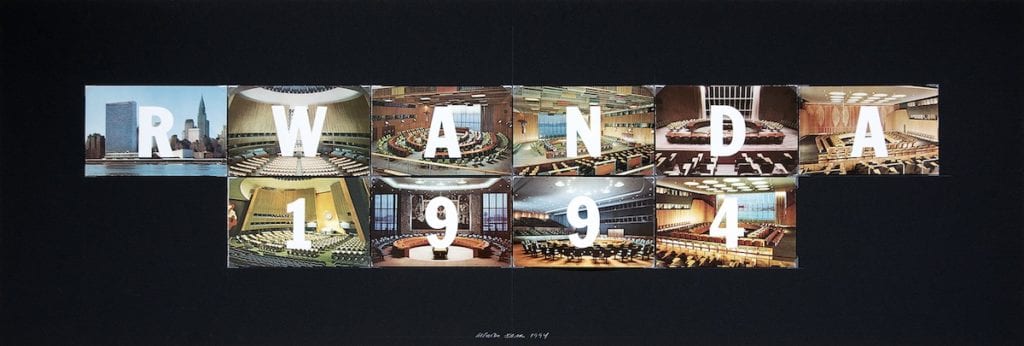

Jaar entered into the situation as a witness, but his work does not reflect the approach that this term may immediately imply. The series, titled The Rwanda Project, comprising over 20 different pieces, six of which are included in the exhibition, is devoid of documentary-style images depicting the death and destruction of the genocide. Jaar took those kinds of photographs but he has kept them hidden. “I did not need to show the horror to talk about horror,” he explains. “That is the logic of the work.”

The artist encountered incomprehensible pain and suffering – he remembers the doctors who left. They could heal patients but they could not comprehend how to speak to children who had witnessed their parents’ murders. He also observed the international community’s immunity to the few images that surfaced in the mainstream press, which depicted the horror of what had occurred. “That is when I thought I have to create a new strategy and language to speak about this,” he explains, “and that is why it became such a long project, with all these distinct works — a futile attempt to tell the story”.

The artist spent just three weeks in the country but worked on The Rwanda Project for the next six years. “I would say that it is impossible to represent the genocide,” he says, “so the project became a series of exercises where I tried one strategy of representation, it failed, then I moved on, I would do another exercise in representation, that would fail, and I would move on”. Jaar explains that each work should provide a different model for understanding the massacre — distinct approaches to comprehending facets of such an incomprehensible tragedy. “I am trying to do something that is impossible to do,” he continues. “How do you convey the magnitude of this event? You do not. You barely scratch the surface.”

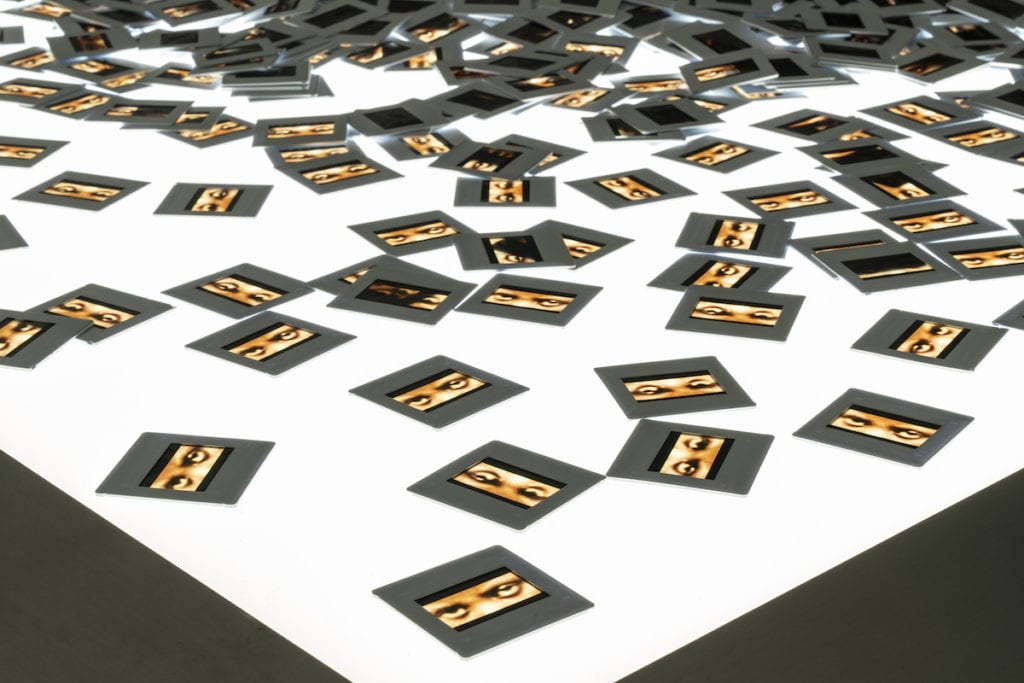

The Silence of Nduwayezu (1997) represents an attempt to reduce the genocide to an identifiable scale. The work comprises one million slides atop an illuminated light table, all of which depict the eyes of Nduwayezu — a five-year-old Tutsi boy who witnessed the murder of his parents. The eyes, which exude a deep sense of anguish, stare out at us. They embody the horror of the genocide as experienced by one child, while symbolically representing the magnitude of the suffering through the number of slides contained. The piece is also emblematic of the international community’s silence. “When we look deep into his eyes, we are finally seeing what he saw,” continues Jaar, “and what the world refused to see, in its criminal indifference and silence”.

In other works that focus on individuals, the subjects turn away. Six Seconds comprises a blurred image of the back of a young girl wearing a bright blue dress. Jaar encountered the girl in the Nyagazambu refugee camp. He was with her for just six seconds as she discovered that Hutu militia had murdered her parents. The cloudy quality of the image is central to the piece. It symbolises Jaar’s inability to communicate his subject’s inconceivable reality. “When we try to communicate the reality of someone else … we never really have adequate language because we are trying to explain something that happened to someone else,” he says. “So, in a way, everything we do is out of focus.”

“When we try to communicate the reality of someone else … we never really have adequate language because we are trying to explain something that happened to someone else. “So, in a way, everything we do is out of focus”

The work operates on two levels: it is both informative and evocative. The pieces should equip us with an understanding of aspects of the genocide, but they should also make an emotional impression. “If you affect a few people, maybe next time a similar thing happens they might have the intellectual and the political tools to react on time.”

The series is also significant in other ways. Today our visual landscape is awash with billions upon billions of images. Jaar warns against their seeming innocence. “As kids, we are taught how to read and write, but no one teaches us how to perceive images,” he explains. “This is a fundamental issue that we face as a society.” Without a critical eye, we consume photographs without question; they affect how we think and perceive things. The Rwanda Project endeavours to challenge this. The work isn’t straightforward; it encourages us to question what it depicts. It forces us to think critically about the subjects at hand.

Alfredo Jaar: 25 years later is on show at Goodman Gallery, London, until 11 January 2020.