This article was published in issue #7892 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

In the winter of 1942, readers of popular monthly magazine Lilliput opened their December issues to find a special feature on London’s air raid shelters, with drawings by Henry Moore side by side with photographs by Bill Brandt. The sculptor and the photojournalist had worked independently, so the meeting of minds occurred only, as it were, in print.

But the pairing proved an enlightened editorial choice, with both men’s images closely attuned to the strange and claustrophobic monotony of this subterranean world. On adjacent pages, we see Brandt’s Tube Shelter and Moore’s Four Grey Sleepers, their subjects asleep, nestled in ranks, like sandbags. Brandt’s deep, suffocating blacks – the outcome of refinements in the darkroom – find their counterpart in Moore’s concentrated strokes and shadowy liquid washes. The bodies are caught up close, in cropped compositions, trapped by the perimeters of the page.

The artistic encounter in Lilliput provides the starting point for a new book and exhibition exploring the pair’s work in tandem, demonstrating, as its editors Martina Droth and Paul Messier write, how their “distinct expressive goals came together through photography and the printed page”. The parallels multiply outwards from the wartime story, leading to an evaluation of the ways in which two artists – one working in two dimensions, the other largely in three – might be found working in sympathy with one another across disciplines.

When that edition of Lilliput hit newsstands, both Brandt and Moore were working for the Ministry of Information, their primary channel being newspaper reproductions of their work. It is through these means that each reached audiences numbering in the millions on a routine basis. Indeed, their images of shell-shocked Britain became synonymous with the nation’s memory of these years, inked indelibly on its collective psyche.

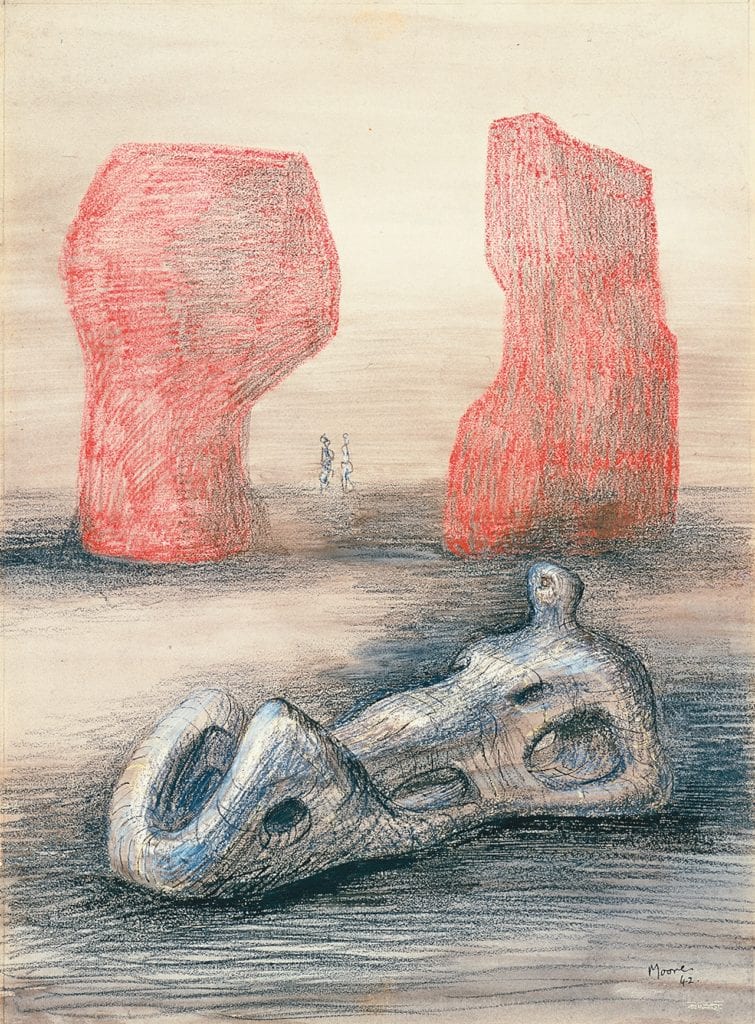

Given this, perhaps it is little wonder that both were careful to craft their images with this end in mind, studiously deploying effects with an eye to how they might translate on the flattened printed page. Brandt’s prints bear witness to his precise interventions, brushing on dyes and incising surfaces with a blade – painter, sculptor and photographer alike. Moore too, produced not just sculptures but striking, large-scale images of them, each one “a powerful spectral offshoot… [to] magnify his sculpture’s presence”.

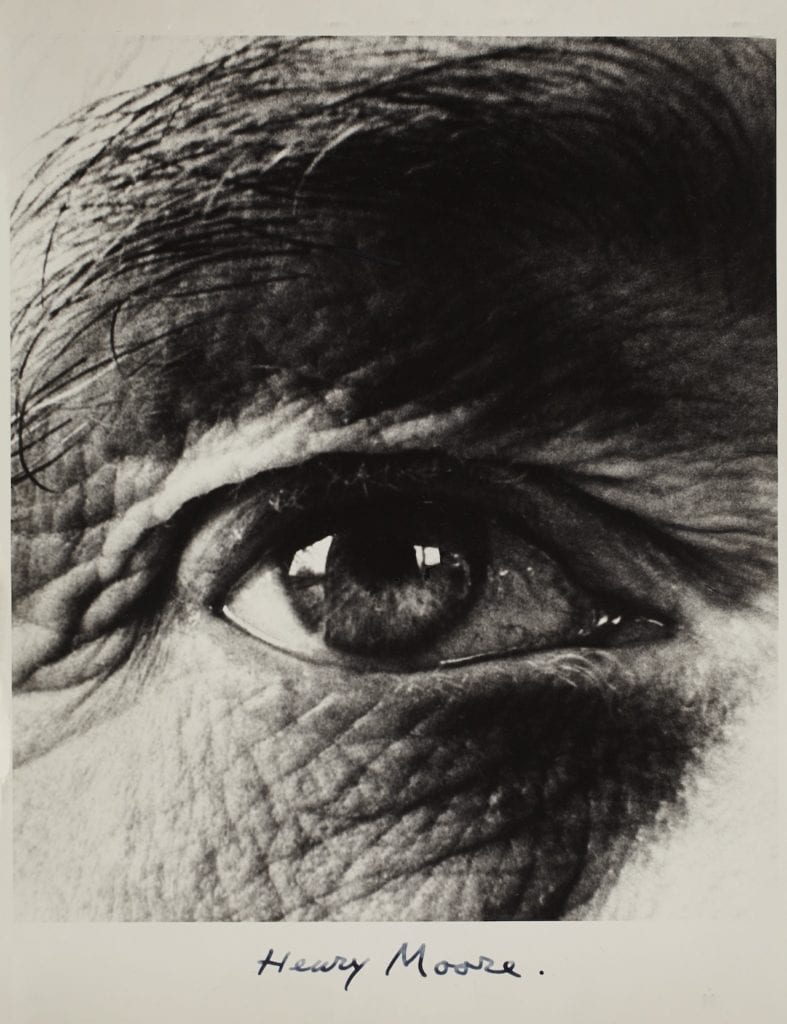

After the war, Brandt began a period of lyrical experimentation, which saw him depart from the conventions of documentary photography. As well as establishing himself as a leading portraitist for titles such as Harper’s Bazaar (for which he photographed Moore), his greatest aesthetic satisfaction appears to have come from Britain’s ancient, uninhabited landscapes. Likewise, Moore emerged from the rubble to discover afresh the rugged beauty of his homeland, scarred in places, but otherwise reassuringly unchanged.

Thanks to their incursions into the land, both men found subject matter that would yield inspiration for the duration of their careers. In Britain’s megalithic sites, geological formations and prehistoric man-made structures, they were to alight on the spare and monumental drama that would provide the keynotes to their work. Stonehenge in particular, had an elemental importance, and both returned to it time and again, as if to siphon from it the expression of something essential about shape and form.

The human – often female – body became an enduring theme too, its taut curvature eliding with the landscape in both men’s postwar work. Through dedicated chapters, we learn of the two artists as beachcombers, collecting fragments of rock, pebbles and driftwood in order to make relief sculptures, at times reminiscent of the human form.

Brandt would pocket flotsam to organise into careful assemblages, fixing these in Perspex boxes as three-dimensional artworks, or photographing them in black-and-white. More surprising is this unfamiliar facet of Moore’s practice, with the sculptor using stones, shells and bones to make temporary sculptures that he would photograph and then disassemble. In turn, these prints would provide him material for collages, with the sculptor cutting and pasting his images into new and inventive creations.

Showing the two men’s unique visions develop in step, the narrative of the book, Bill Brandt/Henry Moore – which accompanies an exhibition at The Hepworth Wakefield (07 February to 31 May), which then tours

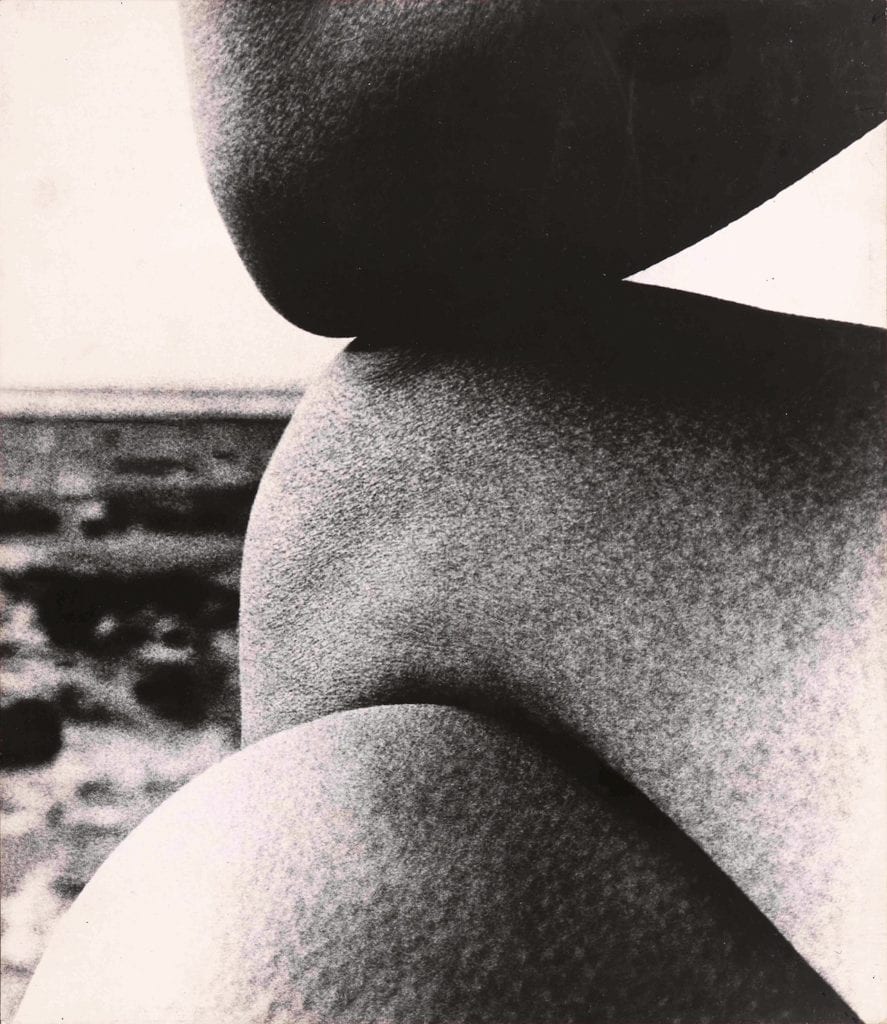

to Yale Center for British Art in Connecticut (25 June to 13 September), who published the book in association with Yale University Press, and then to Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich (22 November to 28 February 2021) – elucidates how both probed the possibilities of photographic technology, exploring the ways in which it could and could not transmit the tactile truths of the organic world. This reaches an apotheosis in Brandt’s series of nudes, published in 1961.

Indebted in part to Moore’s own studies of the body, Perspective of Nudes pares the human figure down to a suggestion of pure form, distilled into abstraction against a shoreline, as if smoothed by tides. As Moore did with his famous figures, Brandt reaches calm clarity in these images which elevates his work to the iconic, an object lesson in taking solid mass, and melting it into shapes of lasting wonder.

Bill Brandt/Henry Moore will be on show at The Hepworth Wakefield from 07 February until 31 May 2020. The accompanying book is published by Yale University Press.

—