This article was originally published in issue #7894 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

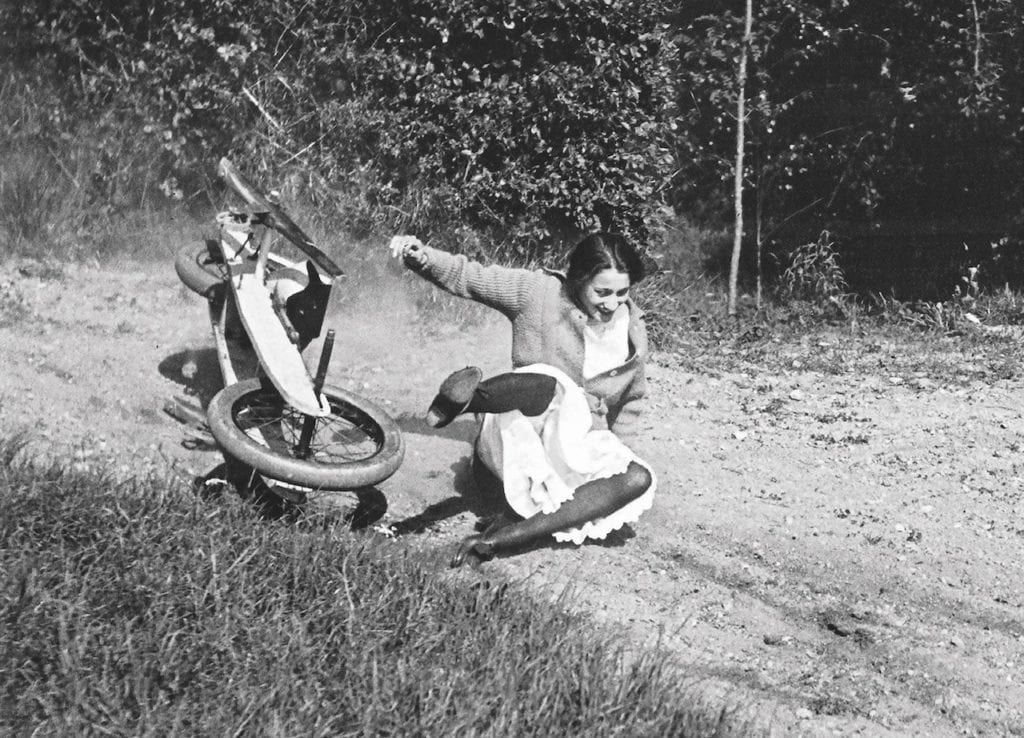

Model airplanes, high-speed Peugeots, kites, winter sports, silk dresses and ostrich-feather hats — these shiny pastimes and fixtures comprise the mosaic of elaborate subject matter associated with Jacques Henri Lartigue, a boy raised in the gilded era of France’s Belle Époque. Aside from his knack for capturing quirky and fashionable moments amongst family, friends and passers-by, what makes the decorated childhood of Lartigue so enchanting is his artistic evolution alongside the rapid ascendancy of the photographic medium itself.

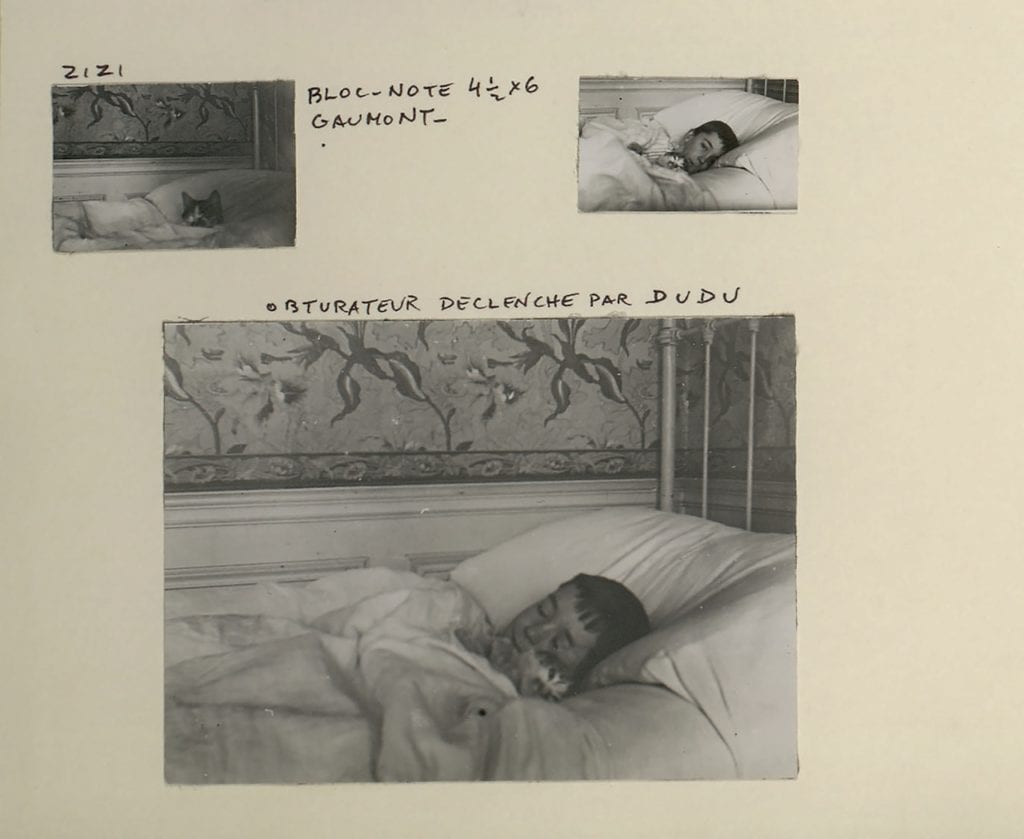

Born in Paris in 1894, Lartigue was given his first camera around the age of eight, and soon after began developing his own photographs. Isolated in the small bubble of the Parisian noble elite, Lartigue’s father was a successful businessman who encouraged his son’s pursuit of the scientific hobby. And as the consumption of photography swelled, so too did innovations in the medium, resulting in quicker exposure times and advanced equipment capable of recording movement.

Based between Paris and his family’s summer home in Normandy, the young Lartigue photographed his brother Zissou’s automotive and aviary creations together with the playful antics of extended family members drifting through a bourgeoisie dreamworld sequestered from the surrounding social and political reality. Even after the invention of the widely accessible Kodak Brownie, Lartigue continued working with large and medium format cameras, prioritising sharp precision over instantaneous flatness. Mastering the more challenging technology, he created detailed photographs of everything from beach-goers to indoor still lifes, candidly recording famous figures dripping in the latest fashion trends one day, and photographing race cars whipping past him the next.

But after years of immense richness, the Lartigue family experienced a financial hit in the wake of the First World War, and their fortune was ultimately decimated in 1929 in the Wall Street Crash. The freedom and access Lartigue had grown up with was no more, and he started painting to support himself, never again reaching the status and wealth he was so accustomed to in his youth. His previous life frozen in time through his photographs, Lartigue spent the following decades resequencing his images into countless volumes, embodying a real-life Peter Pan who never quite figured out how to grow up.

When John Szarkowski, director of the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, was introduced to the 69-year- old Lartigue in 1963, he was immediately enchanted by the childhood photographs. He organised a show of Lartigue’s work, defining him as a child prodigy of technology and aesthetic sensibility, framing his luminous, frenetic visuals as a testament to his innate artistic eye. In 2004, Kevin Moore revisited this hagiographical approach in Jacques Henri Lartigue: The Invention of an Artist, instead situating Lartigue as one member of a larger community of amateur photographers, fortified by a culture of countless manuals, clubs and resources. Under Moore, Lartigue’s narrative shifted from child genius to privileged member of a cultural elite who had easy access to the tricks of wielding a camera.

Even though Moore effectively shed light on the understudied culture of amateur photography in France’s lost class of aviation enthusiasts, winter athletes and scientific hobbyists, Lartigue’s playful photographs continue to captivate audiences to this day. This perpetual allure suggests that the once-forgotten photographer’s legacy is less aligned with the extremes of child prodigy and mundane amateur, and instead lays somewhere in between.

In her new book, published by Thames & Hudson, titled Lartigue: The Boy and the Belle Époque, art historian Louise Baring balances these narratives by socially contextualising the first 20 years of Lartigue’s life. Discussing

the evolution of the photographic medium alongside the photographer’s own growth, Baring presents Lartigue’s biography in the context of the art and culture of his time, weaving his history into the greater framework of his artistic, social, and technologically innovative surroundings.

Having scoured the Lartigue archives in Paris, Baring includes plenty of excerpts from the photographer’s diaries, incorporating sketches that demonstrate his impeccable memory for the construction of visuals, even before he developed his images. Outlining the sources of Lartigue’s excitement about and inspiration for his photographs, Baring fleshes out his brother Zissou’s adjacent obsession with technology, their father’s interest in cinema, and their mother’s attention to fashion, bringing the Belle Époque to life through external source material and anecdotes. In Baring’s retelling, Lartigue’s naivete about his surroundings is laid bare, shaping a character best described as a privileged boy nonetheless imbued with artistic innovation – a balance between previous interpretations.

Lartigue: The Boy and the Belle Époque is published by Thames & Hudson.

—