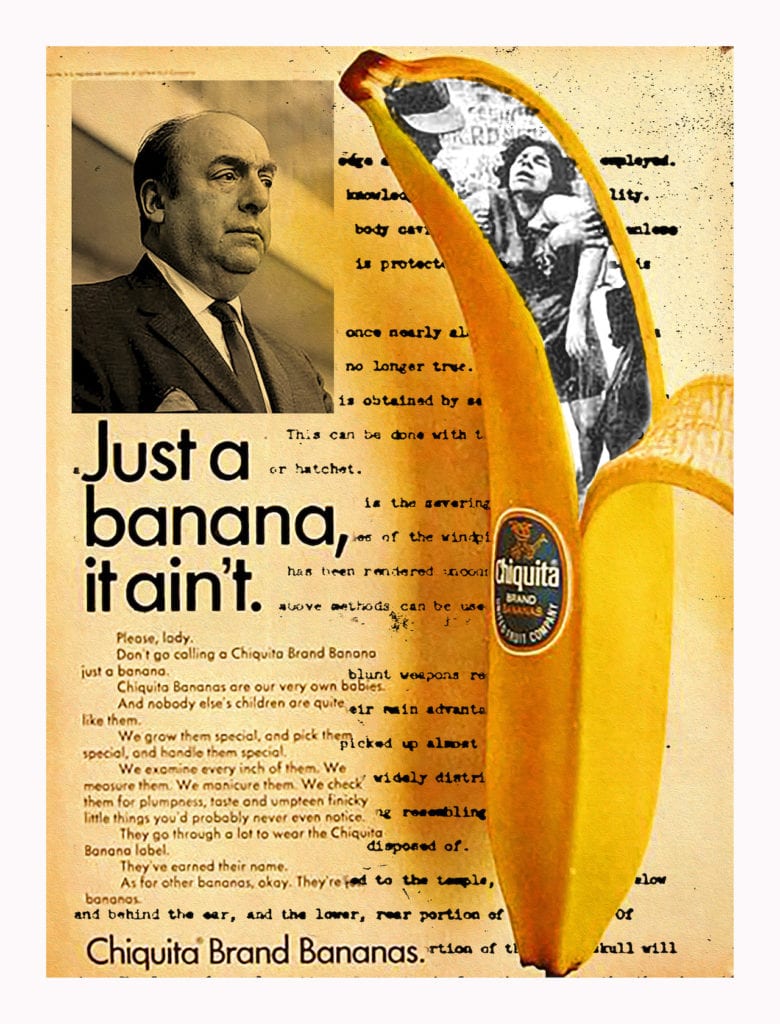

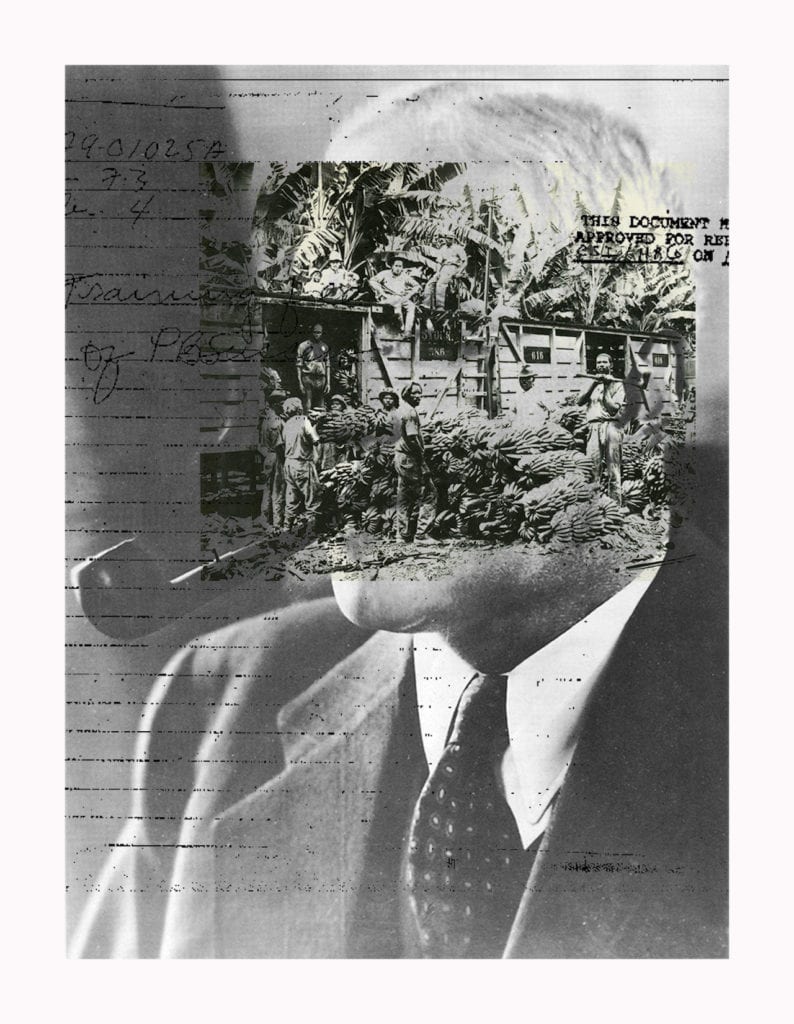

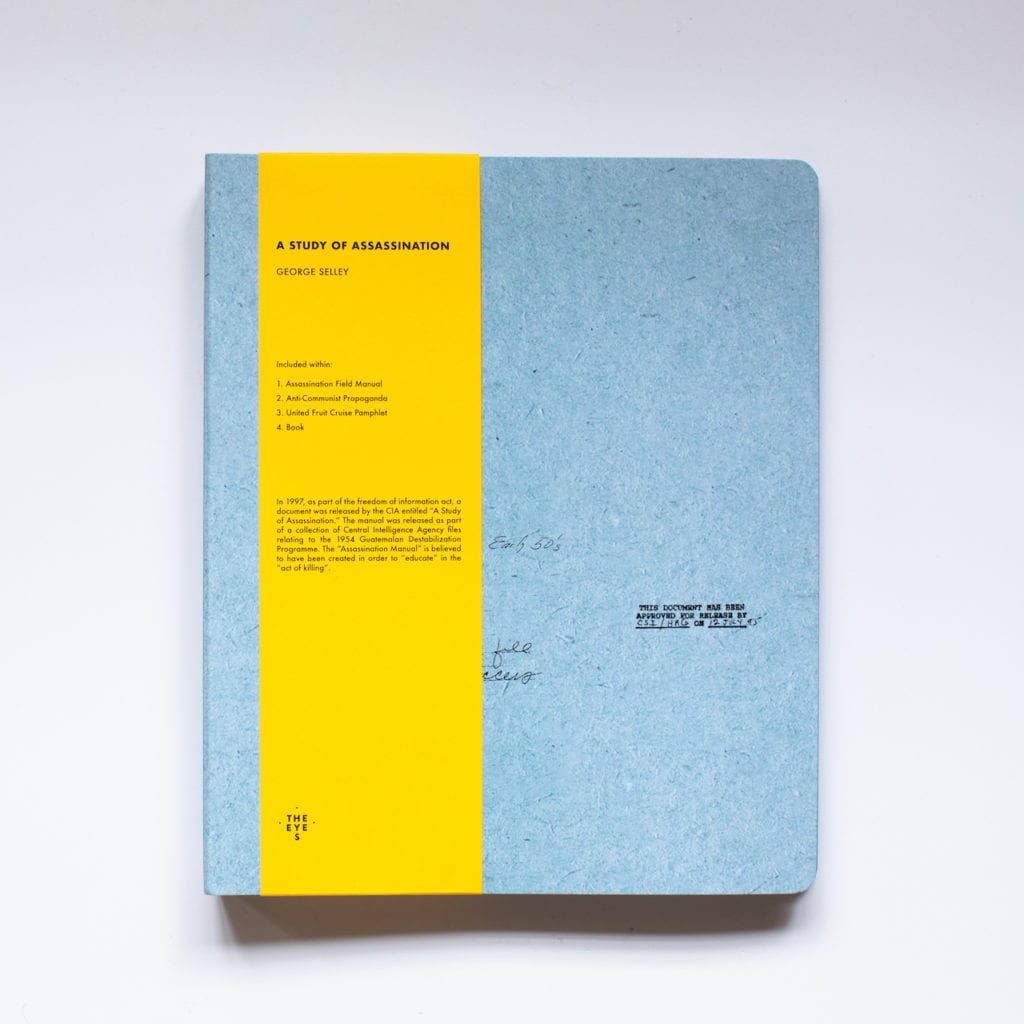

When BJP-online first met George Selley, a London-based photographer who employs photomontage to create research-intensive and politically-charged works, he highlighted political artist Peter Kennard as an important inspiration for his first photobook, A Study of Assasination.

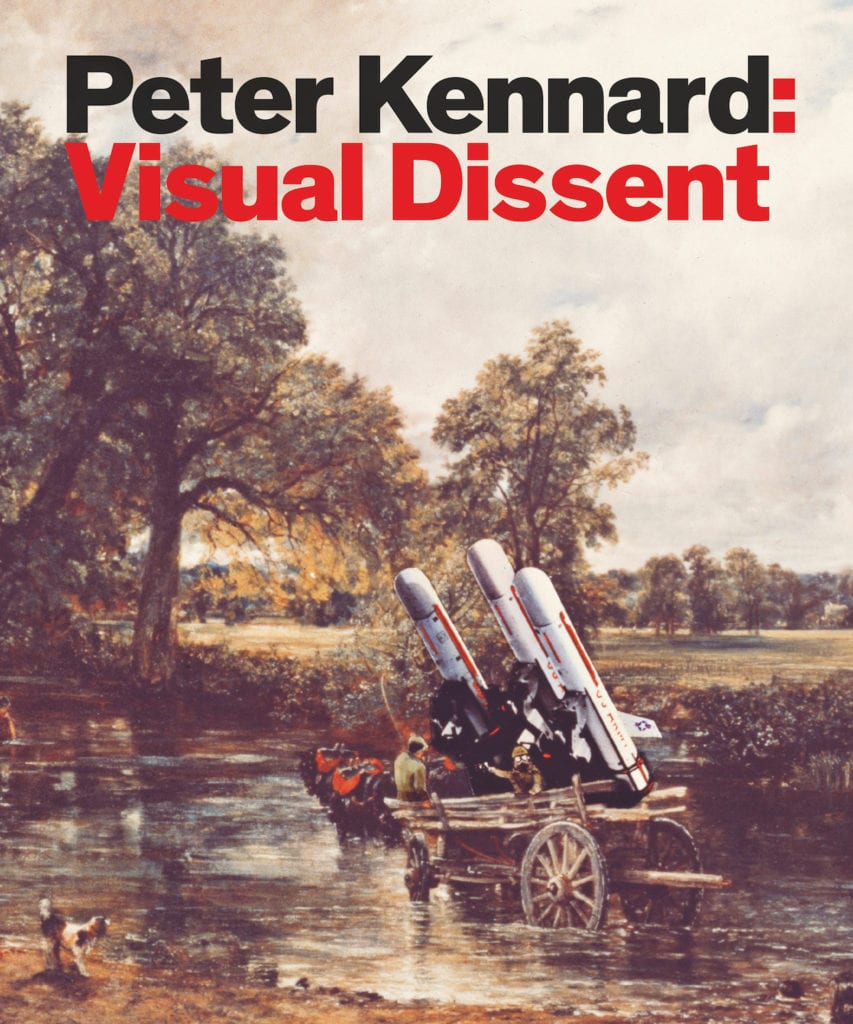

Kennard, who is best known for his work for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in the 1970s and 80s, studied at The Slade School of Fine Art in the late-1960s, during which he became involved with the anti-Vietnam War protests. He currently works as professor of political art at the Royal College of Art.

Three months ago, Selley sent Kennard a copy of his photobook. The pair have never met, but during the current lock down, they were able to connect over video-call. Here, we present their conversation, in which they discuss the importance of making accessible art, and the role of photomontage in protest and times of crisis.

George Selley: Hi Peter.

Peter Kennard: Hi George, how are you keeping?

GS: I’m okay. I’m one of the lucky ones, I suppose. And you?

PK: Me too, I’m at home in Stoke Newington in Hackney. I haven’t managed to get to my studio, so I’ve been here, but I feel very aware of what people are doing out there. It’s so weird, isn’t it? It’s quiet where I am, there’s no one around, and yet everyone is aware of what is going on in the hospitals. Where are you?

GS: I’m just down in Peckham. It’s strange how drastically different people’s experiences of this will be. I remind myself of that all the time, that it’s not the same for everybody. I wanted to ask how you see the crisis, from a larger perspective. Some people see it quite negatively — that it could become a catalyst for more authoritarianism and increased nationalism — but some people see it as an opportunity for positive change.

PK: It depends what side of the bed I get out of. One day I think it opens up the possibilities for a different world — a better world. The next day I wake up and think, “Fucking hell, we’ve got Trump, Johnson, all these characters — they could get stronger out of this and dictatorships could actually embed themselves even more”. Other days, I think people will become more aware. There’s lots of different possibilities that come out of it, some very negative and some positive. I think in terms of the climate, it could be positive. We’ve realised we’re not all-conquering humans — we can be slayed by a virus.

“Getting the message out to the people who are engaged in the struggles I’m addressing has always been important”

Peter Kennard

GS: Photomontage as a medium emerged as a reaction to a crisis — a pretty big one in the form of the First World War. You abandoned painting in the 1970s, in search of new forms of expression, which could bring art and politics together. Why were you interested in merging those two things?

PK: It was because of what was going on in the late-1960s. I got involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement in London, and through that I saw how the police acted during demonstrations — I was at the 1968 anti-war demonstration at Grosvenor Square. When I found out about the atrocities that were actually taking place in Vietnam, I wanted to find a way to make work that related to that. That’s when I started using photography, because photographs of what was going on were in all the newspapers. It was a way to make something that could be used outside of the art realm. I wanted to get away from work that had to be in the gallery, and I saw the leftist magazines and newspapers of that time as a good way to get my work out there.

GS: That’s one of the things that really resonates with me about your work, it’s accessible, and it makes direct statements. Thinking of Photo Op — the image of Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of a burning oil field — almost anybody can engage with it. Is accessibility something that you place importance on?

PK: That was one of the images that came out of a collaboration with Cat Phillips. Something that I’ve always been concerned with is the audience. If you want to actually engage with people in a real way, politically, making work for a small elite art audience doesn’t work. I’m aware that in making work accessible, sometimes it loses its subtlety, but if I’m doing posters for the street, they’re up against corporate media so you have to do something that gets through to people in a few seconds. That’s always been really important, getting the message out to the people who are engaged in the struggles that I’m addressing.

George Selley

Do you feel that you are treading the line between being an artist in the art world, and being an activist?

GS: When I was studying photojournalism I went to a talk at the Frontline Club about Tim Hetherington. The host was explaining an approach that he called the ‘Trojan horse theory’, where he would frame a story as if it was about something universal, like football, but it was really addressing something much deeper, like war. In doing so, he could get people to think about things without them realising that they were there, like the trojan horse — slipping the message in through the back door. Your work is quite direct, but it is similar in approach, particularly through your use of humor and satire. You conceal a darker or deeper statement using a universal language — the visual language of humor.

PK: Humor is a way to get people to look at stuff. I suppose I was influenced by work from the 1930s, like the theories of Walter Benjamin and this idea of a rupture in an image: you break an image open to show what’s actually going on, or what you think is actually going on. That involves humour, because you’re showing that beneath the exterior of politics, there is something completely different. If one can find a way to show it, that in itself is humorous, or darkly humorous, one could say. I think Photo Op, the piece with Tony Blair, works because people find it funny, but in a bleak sort of way. Nowadays it’s difficult to make an image that actually lasts for very long. Billions of images being created every five minutes, so one’s got to find some way of making an image that will last. You can’t really legislate for that, it just happens.

GS: I wanted to ask your advice on something. Often what gets me into a project is a moralistic drive, something that appalls me, or an injustice. But once I start researching abuses of power, it leads me to quite an angry place sometimes, because you come to see how blatant it is and you can’t figure out why it’s not represented in the way that it should be. I find that this anger can alienate the viewer, because in a way, I’ve created a reverse propaganda. Something I’m trying to do more of is to provide the tools for the viewer to deduce for themselves why something is unjust, but then I feel like I’m in a constant battle between telling it straight with passion, albeit in a highly subjective way, and being a little bit more subtle and nuanced.

PK: I relate strongly to that, because I have another way of working which involves a more subjective use of paint and photography — work that doesn’t reveal itself immediately to the viewer, but has a different sort of depth to it, in comparison to work that is very direct. I used to think I could merge the two, but now I realise I can’t, it’s just different ways of working. I don’t think one is better than the other. When I’m looking at the work in your book, it’s totally of you, it’s not something you’ve imposed on yourself, because you think you should, it’s totally integrated into your thinking. I think there is a subtlety in that.

GS: Do you feel that you are treading the line between being an artist in the art world, and being an activist?

PK: I come from a generation that’s ended up creating all this shit for young people now. I’ve been very privileged because I started working as a telephone operator for many years while I was squatting, and then managed to get into teaching. I also got money from doing commissioned work, which enabled me to have a certain freedom to make art that I didn’t have to sell in galleries. That is not possible for young people now, because teaching has become incredibly tough. I’ve always tried to find a way to make political work because I was aware that I wasn’t going to be able to make a living out of it. It’s a sort of scattergun approach, which I think a lot of artists have. You’ve got to keep all the plates spinning at once so you can make it work.

“Right back to The Wasteland in poetry, or Eisenstein in film — the 20th century was very much about the culture of fragmentation”

Peter Kennard

GS: There seems to be a long history of photomontage being present at physical protests — the placard as a symbol is featured in your work. What do you think it is about photomontage that makes it such a staple communicator in a protest?

PK: When you combine two images, a new meaning comes through. And that meaning is related to people’s actions in terms of dissent, and protest. If you have those sorts of images on placards, it has a strong, active effect. The work I did for CND, which is still used on placards, shows an action. The idea was that we should never show these missiles unless they are being broken. One of the things about images of nuclear weapons is that they seem inextricable, like they’re part of nature, and this image shows that they can be broken, they can be destroyed, and something else can come through them. That’s the same with all different forms of montage, which I think is the main tool of art of the 20th century. You go right back to The Wasteland in poetry, or Eisenstein in film, and music and the use of sampling. The 20th century was very much about the culture of fragmentation.

GS: Are you working on anything at the moment?

PK: I did a book called Visual Dissent last year for Pluto Press, which was looking into my 50 years of making work. Now I’m just working with images and seeing what will come from them. I think the way the world is at the moment I’ve got to keep going on in the trajectory of trying to do something quite direct. Especially after the coronavirus, the world’s not going to go back to being the same as it was before. The new normal is not the old normal.

—

A Study of Assasination by George Selley is published by The Eyes.

Peter Kennard: Visual Dissentis published by Pluto Press.

—

—

If you are an emerging photographer interested in interviewing an artist who has influenced your practice, please reach out to editorial@1854.media.

—