This article was originally published in issue #7892 of British Journal of Photography. As a free gift to our community during the coronavirus lockdown, we are offering it as a free digital edition here.

When he was a child, Adi Nes’ mother would sing songs that she had composed just for him. He remembers thinking how markedly idealised and heroic these songs were, evoking the early settlers who had fought to found Israel – strong, determined, powerful men.

“My mother made Aliyah [the migration of Jews from the diaspora to the Land of Israel] when she was five years old,” Nes says over the phone from a small town to the north of Tel Aviv, where he now lives with his partner and four surrogate children. “She married very young. She was very childlike. In her poetry, she expressed a repressed emotional world, her love for nature and the land we farmed. Remembering it now, I can see her poetry discloses, at times, a sense of anxiety. The protagonists of the childhood songs she sung to me were usually men – a soldier, or a father, or both. They were usually stereotypically depicted: the father the strong breadwinner who left for work every morning; the mother sensitive, caring and anxious.”

Nevertheless, his mother – who worked as a librarian – was a true adopted Israeli, who taught Nes to believe wholly in the courage and bravery of the founding fathers of the new Jewish state. Men who, in the years immediately after the Holocaust and in a febrile climate of globalised antisemitism, had established in the Holy Lands written of in the Torah a country that the Jewish people – regardless of wherever they were born – could finally call their own. “She stifled her own Mizrahi Jewish tradition and raised us in light of the Israeli ethos that had formulated by then.”

“I saw myself as a queer, weak, Mizrahi boy from the periphery, different from everyone else.”

However, Nes always felt like something of an outsider. He remembers himself to be a “fragile and sensitive boy” whose dark skin served to visually separate him from the more common and culturally dominant Ashkenazi-Israeli Jews of Eastern European descent. Idylls of masculinity had a particular historical resonance in Kiryat Gat, the small city close to the Gaza Strip where he grew up. Founded by 18 Moroccan-Jewish families in 1954 as a ma’abarot (a Hebrew term for the Israeli immigrant and refugee absorption camps that were formed to welcome Jews fleeing their native countries for a life in Israel), today Kiryat Gat is a frequent target of rockets fired from Gaza.

The idealism of its founding came hand-in-hand with violence. The city lies just to the west of the ruins of the Palestinian village of Iraq al-Manshiyya, which was crushed during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. It has a biblical significance too: Kiryat Gat received its name from the adjacent archaeological site of Gat where – theocratic scholars believe – the biblical Philistines lived. Nes remembers riding his bike through the city’s margins to get to the mountainous place where – it was once thought – David and Goliath fought each other in the Book of Samuel, the biblical history of the founding of Israel.

Nes was born in 1966, a year before the Six-Day War, a central event in Israel’s history – the swift victory over its neighbours fuelling Jewish pride at home and abroad, leading to a new wave of migration, and establishing the ongoing occupation of the Palestinian territories. Nes himself is Sephardic Jewish, his parents having escaped a life of antisemitic marginalisation in Iran. “My mother grew up in a small town in the countryside, in the formative years of Israeli identity,” Nes says. “As a child, many of her neighbours [came] from Kurdistan, but my mother attended the Hebrew school system, and so she experienced the tension between the Zionist ethos and her parents’ cultural heritage.”

“As children, we would call that incredibly tall mound ‘Goliath’s mountain’. I remember riding my bicycle there, picking prickly pears off cacti and eating them while overlooking the city from a distance.” The David and Goliath story assumed a very personal symbolic significance for the young Nes. For, as he hit puberty, he began to realise that something else separated him from this Jewish brethren. “Sitting in my mother’s library, I remember reading references to the homosexual world, and something stirred inside me, nameless,” he recalls. So, as he began to realise that he was gay, so Nes came to associate himself with the young shepherd, armed only with a sling. “As I stood on that mountain, I felt I was David, and Goliath was all the demons I had to battle to overcome.”

One of the many stereotypes that have followed the global diaspora of Jewish men through the ages is that of weakness. From the Crusades through to the current day, they have been depicted as physically inferior – men whom, unable to compete with other men in atavistic fashion, resort to cunning and trickery in order to assert their power. In response, the need to be seen as virile and powerful like the Philistine giant Goliath – became a cultural trope of the new Jewish state. “When Israel was established, the pioneers wanted to create an image of a man that is very different to the weak Jew from the diaspora,” Nes says. “In the early days of Zionism, many voices stressed the need for ‘muscular Judaism’, a new type of Jew of mental and physical strength, to fulfil the goals of the movement.”

It was only as a young man, when he was conscripted to military service, that Nes felt truly part of Israeli society for the first time, a feeling that came from the sense of intense camaraderie amongst his fellow soldiers, as they patrolled the former Palestinian territories. He trusted his life with them, and their life was entrusted to him. “For many years the IDF [Israel Defense Force] was referred to as the melting pot of Israeli society,” Nes says. “Military service is mandatory in Israel. We are an immigrant society, so for many, the army service was a seal of approval for their Israeliness. My father made Aliyah from Iran and fabricated his age so that he would be recruited. By the time he was discharged, he was a different man.

“I was also very proud to serve in the IDF. I saw myself as a queer, weak, sensitive Mizrahi boy from the periphery, different from everyone else. But very quickly, already during basic training, I felt that I was part of this great power. The IDF uniform worked like a magic cloak. I was part of an ultra-masculine unit – we were completely devoted to one, and one to all. The long distance and time away from home and the intensive stay with my friends made me feel that they were my new family, the military ethos binding us together. I felt we were one.”

But Nes did not totally sign up to the militarist jingoism of the Israeli state. He remembers being drafted as a reserve to guard a Palestinian detention house. Bit by bit, he began to share details of his life during long conversations with one of the prisoners he was guarding. Nes carried a loaded rifle, and would lock the man in his cell each evening, but soon realised he considered the prisoner to be his friend – a man to whom he was not capable of bestowing violence. If the prisoner launched an escape, Nes realised he would behave treacherously; he would not be able to shoot his Palestinian friend.

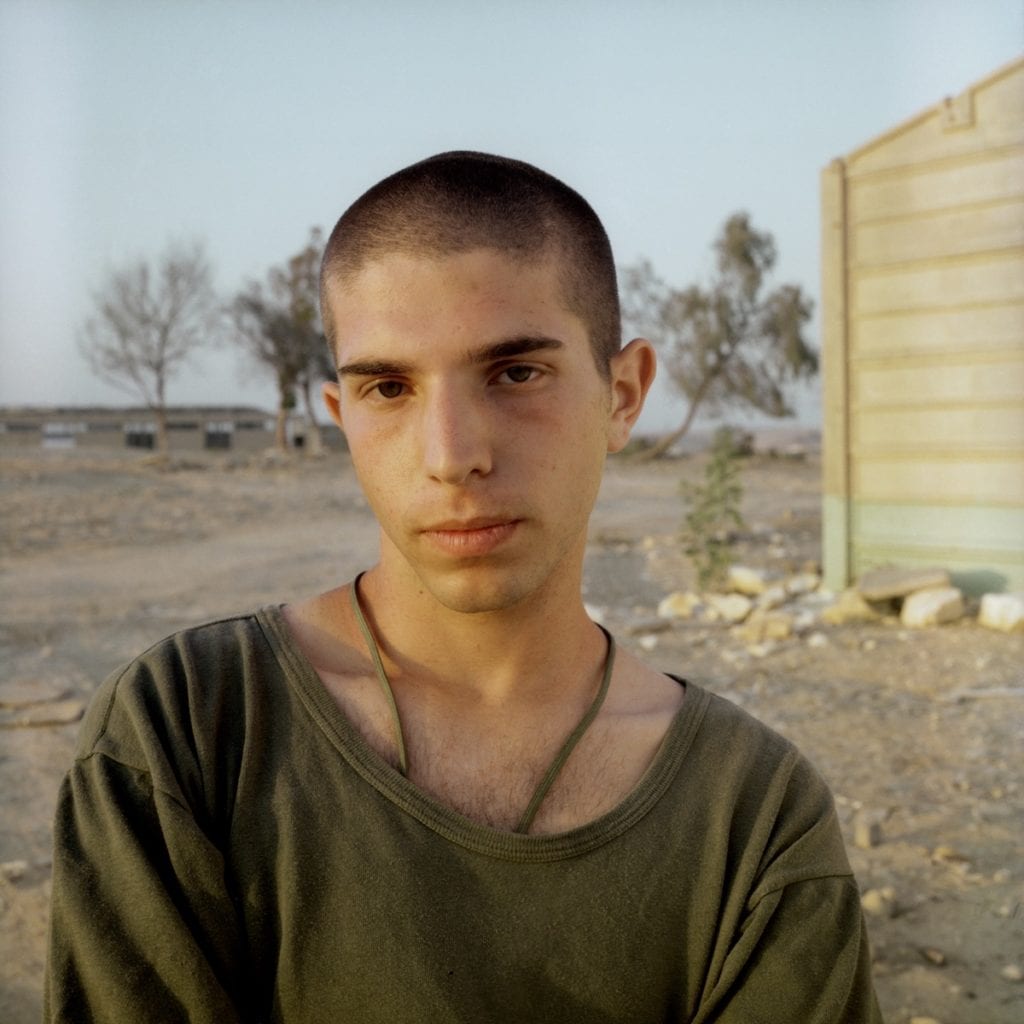

While studying at the photography department of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem in the early 1990s, Nes became absorbed in the artworks that depicted the stories he had read in his mother’s library. He became an avowed student of the history of Renaissance and Baroque paintings, and the Greek, biblical and Roman parables of sin and innocence, hubris and tragedy that those paintings tell through tableaux and gesture. And now comfortable in his sexuality, he started to photograph masculine beauty. He has described his favoured subjects as “men who look you straight in the eyes with their blue eyes, even though their lives are strewn with tragedy”.

Soon after, in 1994, Nes began working on a series that he would continue to develop, on and off, through to 2000, and is part of the Barbican Art Gallery’s Masculinities exhibition (which opened 20 February, and was due to run until 17 May, but was forced to close during London’s coronavirus lockdown), in the opening section titled ‘Disrupting the Archetype’, alongside artists including Richard Prince, Wolfgang Tillmans, Rineke Dijkstra, Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts. The images were, Nes now realises, informed by the gendered depictions interwoven in his mother’s songs. “Without having noticed it before, I realise now that in my photographs I challenge exactly the stereotypical masculine imagery that she sang about,” he says. “I allowed my subjects to be sensitive, childlike and anxious.”

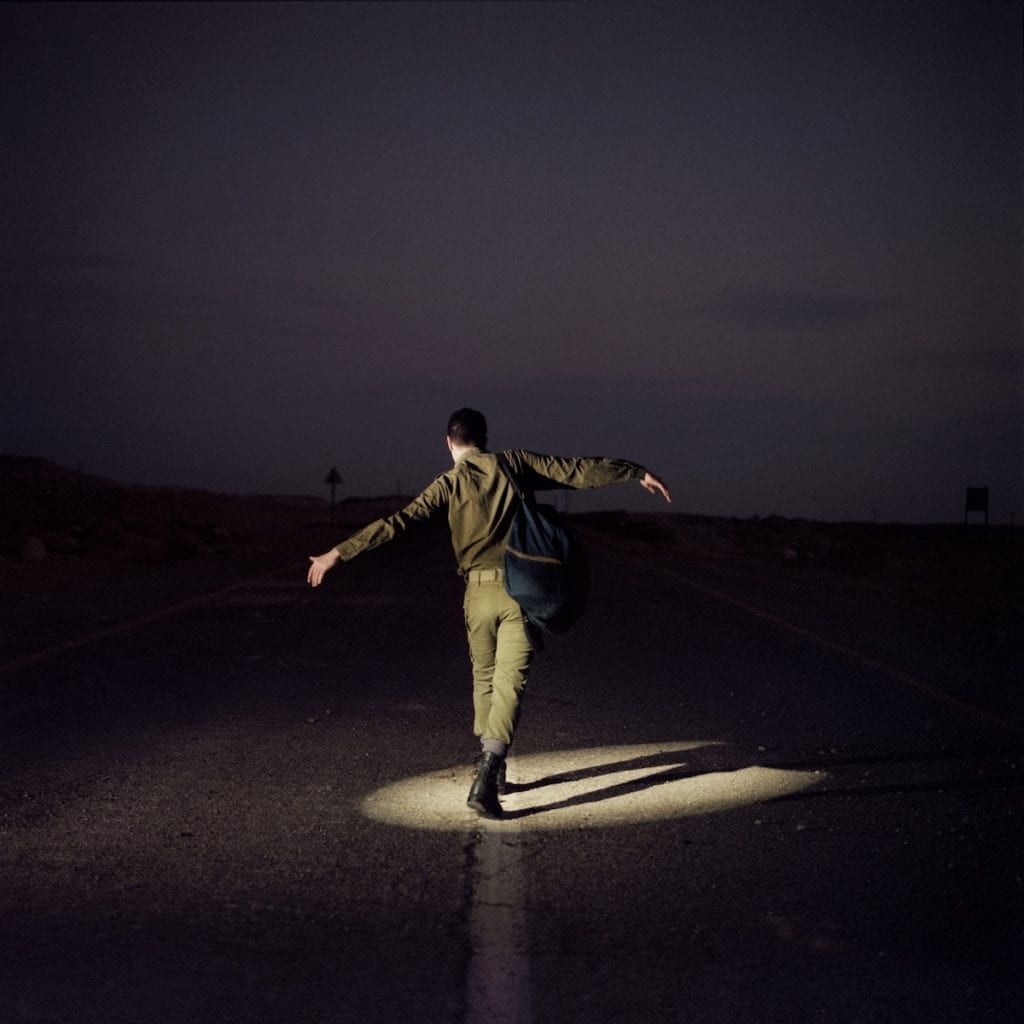

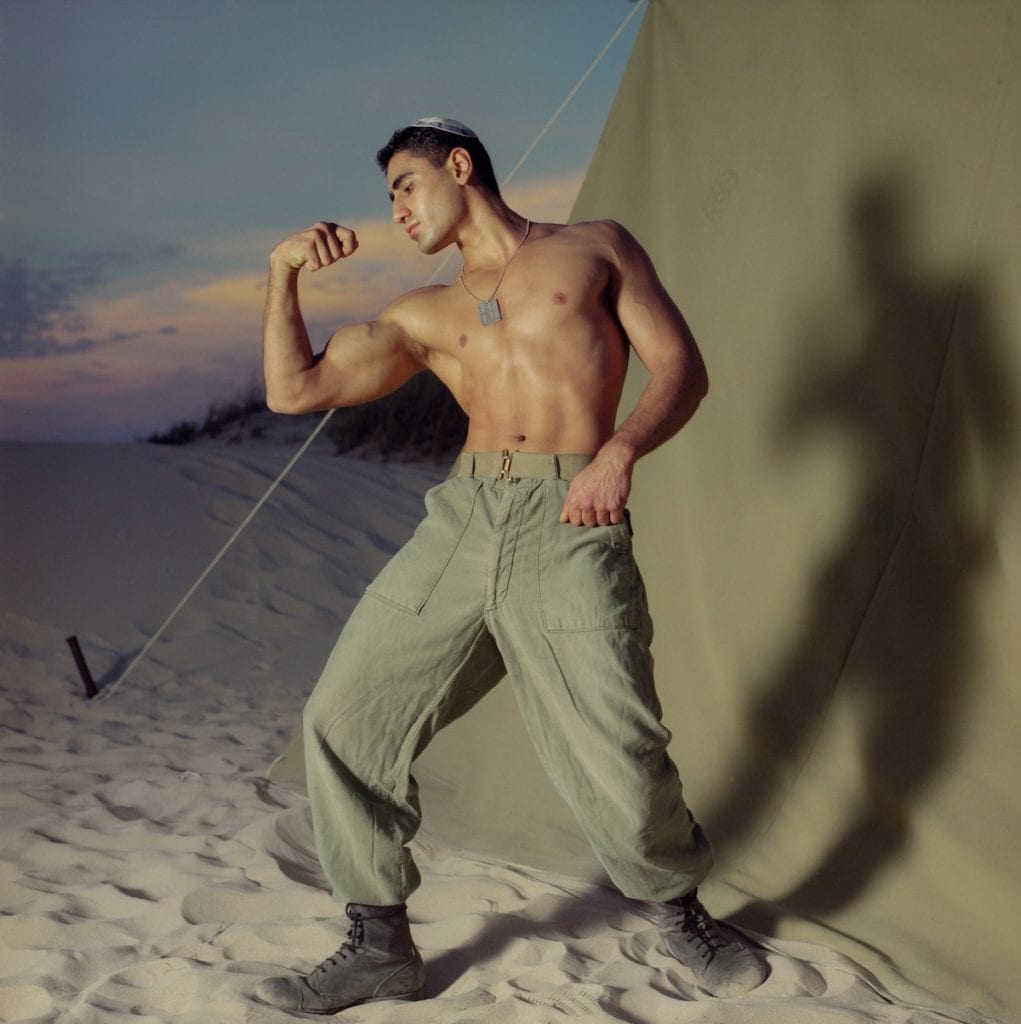

Titled Soldiers, and comprising 22 staged photographs, the series consciously subverts the stereotype of the masculine Israeli man invoked in his mother’s songs. In his own telling, using the wrought narratives of Renaissance painting as conscious inspiration, Nes imbued the macho tropes of the Israeli military with homoeroticism, intimacy and vulnerability.

An early image from the series (above) depicts a muscular, bare-chested man clad in combat fatigues, dog tag and a skullcap, engaged in an apparent performance, flexing his biceps and pursing his lips. Behind him is a military tent, yet he appears alone at sunset in the desert, the sand stretching to the horizon. Then there’s the soldier tenderly dressing a comrade’s war wounds (below). But look closely and you’ll notice the wound is being treated or perhaps faked – via the application of makeup.

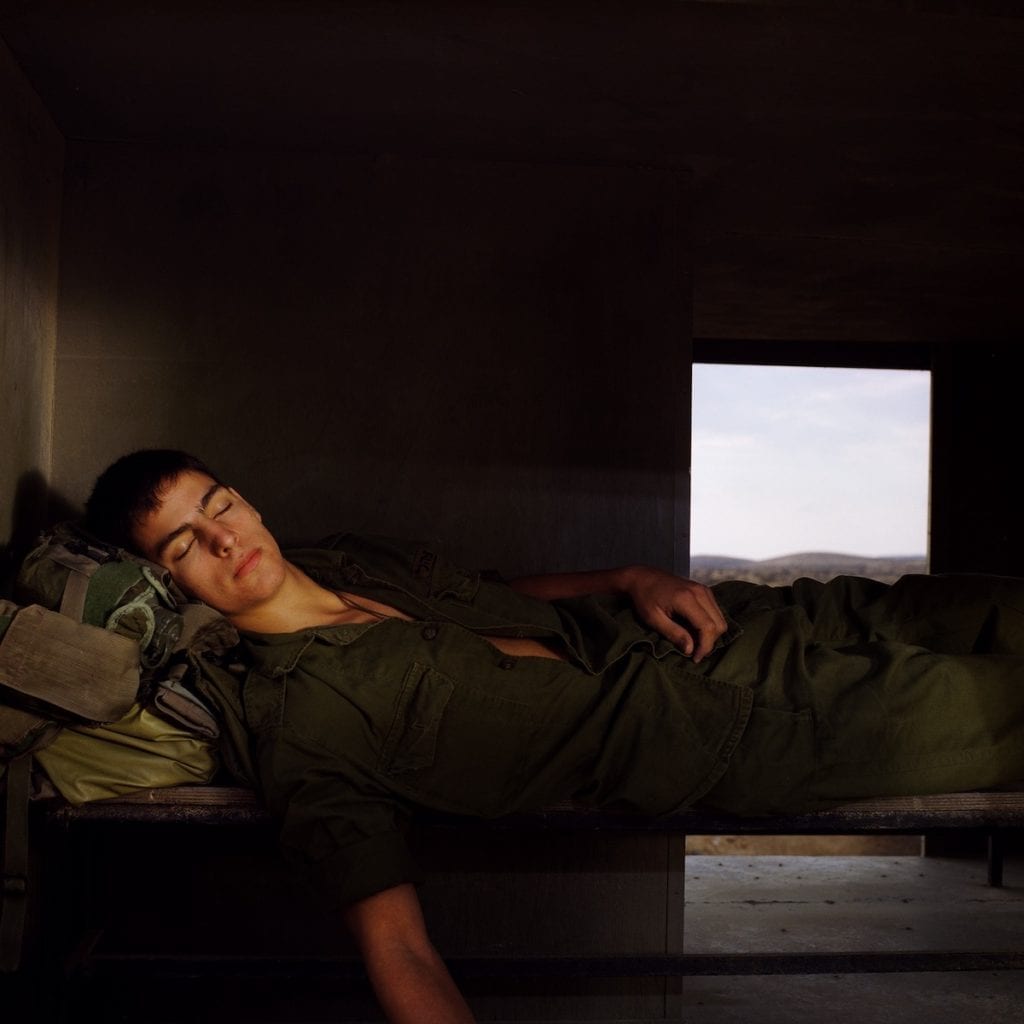

Like Tim Hetherington’s later imagery from Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, the boyish vulnerability captured in the sleeping repose is an ongoing trope in Soldiers. Subjects slumber while leaning against each other, their rifles visible, their heads resting on laps, their limbs intertwined. They’re like kittens dressed for war. Or, maybe, we are witnessing the strewn, lifeless corpses of once-vibrant young men.

“Before starting work on the Soldiers series, I decided my subjects would never be in combat,” Nes says. “They would always be in between. They eat, sleep, take a piss, but they never fight. Still, death is always present, lingering. The sleeping soldiers on the bus look as if they may be dead, because, as I was working on these pieces, suicide bombers were blowing themselves up in buses.”

“The sleeping soldiers on the bus look as if they may be dead, because, as I was working on these pieces, suicide bombers were blowing themselves up in buses.”

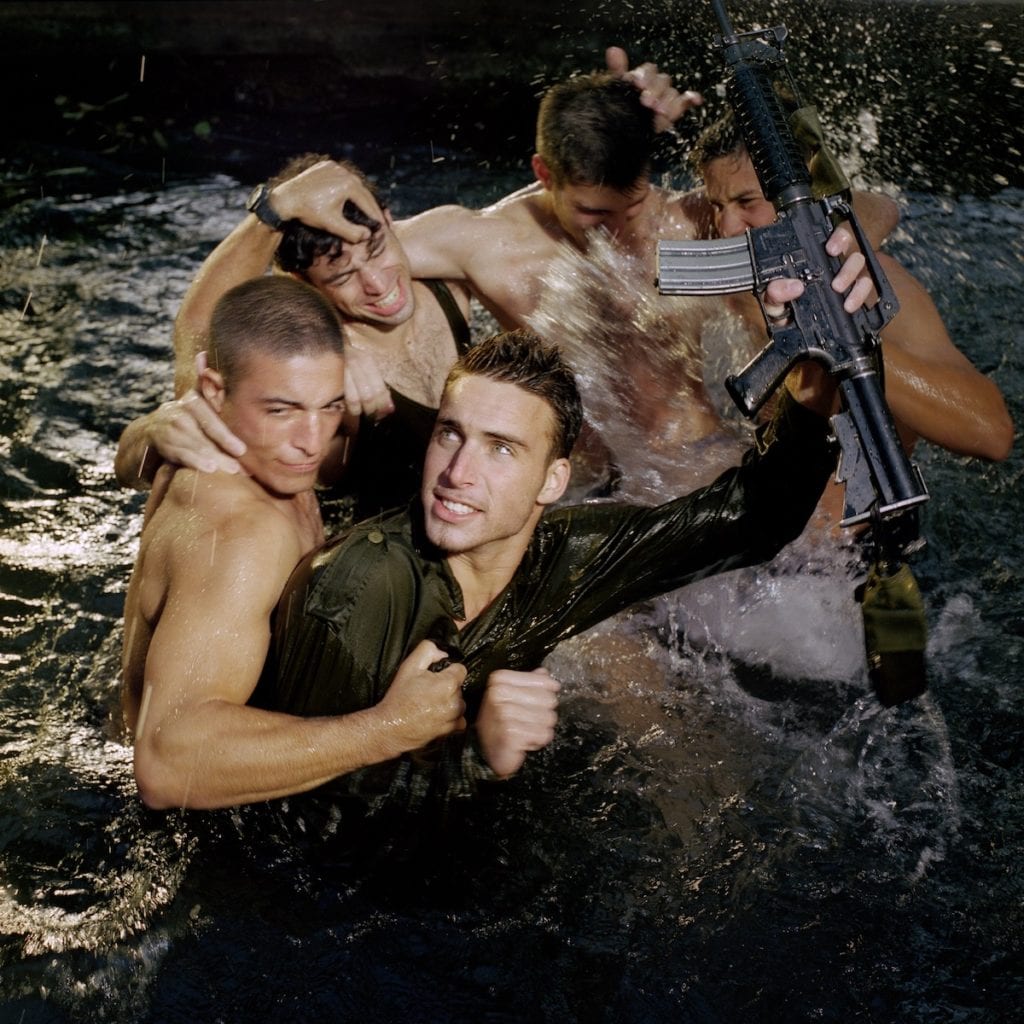

Autobiographical elements are interwoven. Nes often shoots dark-skinned Israeli subjects of a similar Sephardic descent, and tellingly, one of the images, of soldiers in water (below), references the Yossi Ben-Hanan iconic photograph that appeared on the cover of Life magazine on the last day of the Six-Day War – the event that had such a dramatic impact on Nes’ early years in Kiryat Gat.

“Ben-Hanan’s photograph was probably the most accurate reflection of the euphoria that followed the Israeli victory after the Six-Day War,” Nes says. “It showed a handsome Israeli soldier – the quintessence of the fierce, blue-eyed Sabra – swimming in the Suez Canal that had just been seized by Israel.” The photograph radiates the optimism of the victors, Nes says, after they had “freed and seized” the West Bank and the Sinai.

As Nes grew into himself and found his voice as a photographic artist, the image came to possess many of the conflicts and complexities that are built into the modern Israeli national psyche.

“During the formative years of my identity, we were exposed to a recurring narrative: few against many, overwhelming victory, and hope for peace in the air,” Nes says. “But, as the years passed, it transpired there were other aspects to our victory – there was now a population under our military control.” Nes’ re-creation of BenHanan’s photograph sought to express the weight of the occupation. “The blue water on the cover of Life turned black and troubled in my photograph,” Nes says. “The soldier is not alone, but surrounded. The cold water I shot in this photo caused the model’s lips to turn blue, and his image expresses not only courage, but also anxiety. It is a sober gaze into the future.”

Perhaps his best-known image (below), taken in 1999 – and sold at a Sotheby’s auction eight years later for $264,000 – shows young soldiers seated at a long plastic table at an army base. Their olive-green army fatigues contrast with the red cups that populate the table. They laugh, joke, compete and caper, light each others’ cigarettes and steal each others’ food. Sub-titled Last Supper, it depicts the moments before the men leave the protection of the mess hall to head for battle, and, of course, it consciously evokes Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

“Two years before I took this photograph, I was on my way to a café in Tel Aviv when I heard the loud explosion of a suicide bomber,” Nes recalls. “He had blown himself up in a restaurant. I guess, from that moment, I made the connection between eating and death.” Da Vinci’s Last Supper was not arbitrarily chosen, he says. “I was looking for an icon – something that would be immediately recognised by the viewer,” he says. “I wanted the viewer to see a group of soldiers eating and immediately be struck with the sense of impending death in the photo. Death, in my photographs, strikes at the most trivial moments, and not at the heroic ones.”

Like his mother’s songs, these images are elegies of modern Israel. Each image is caught between fragility and strength, innocence and sin, life at its most lived and death at its most senseless. They depict the original dream of a peaceful Jewish state, and the stark realities that grind through our newsfeeds every day. They are war-torn, tragic, self-questioning, and beautiful as well.

—