Due to ongoing regulations around the world to stay home during the Covid-19 pandemic, many photographers have started creating work from isolation, adapting their usual creative processes to make the most of their time indoors.

However, for many photographers, making work indoors is not a novelty. From working within the four walls of a studio to unpacking archival photographs, and employing themselves as the subject, the artists featured in the second instalment of Great works made from home regard confinement as an opportunity, rather than limitation.

Tania Franco Klein’s exploration of technology and loneliness

In The Burnout Society, philosopher Byung-Chul Han asserts that the overload of technology and the “culture of convenience” are catalysts for depression and various personality disorders. Mexican photographer Tania Franco Klein places this reality at the centre of her first monograph, Positive Disintegration, which was shortlisted for last year’s Paris Photo Aperture Foundation PhotoBook award.

“We have these compulsions to perform and we live in a society of achievement and positivity that has led to a constant fatigue,” says Franco Klein, in an interview first featured in British Journal of Photography’s Female Gaze Issue, now available to revisit in a free digital edition.

Seen through the eyes of fictional female characters, played by Franco Klein, who assume hunched positions, the series was shot in various rooms of a 1970s-style house. Performing as these characters, Franco Klein smokes cigarettes, stares at the television, and lies on the floor.

“It’s funny because I’m talking about isolation, but, at the same time, I realise that doing self-portraits isolated me more,” says the photographer. “We are always trying to create identities with social media to express the good parts of ourselves as if there is some kind of shame in knowing what we are on the other side … because we feel that we have failed in what we are supposed to be.”

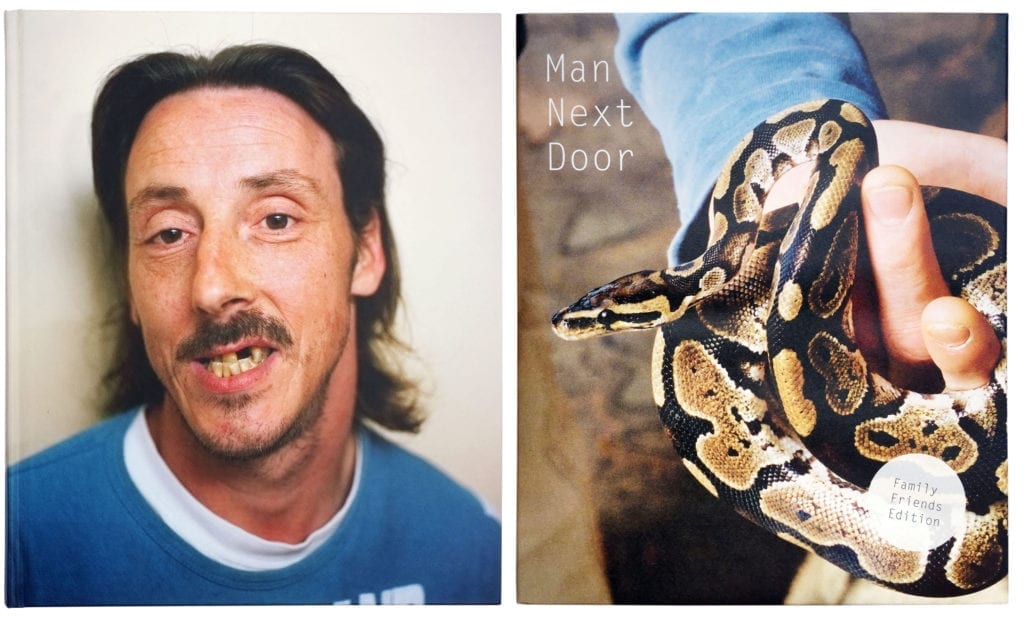

Rob Hornstra’s portrait of the Man Next Door

“Kid was a bit of a boorish figure – a troubled man with limited capacities,” says Rob Hornstra, referencing the subject of his project, Man Next Door, in an interview with BJP-online in 2017. Kid was Hornstra’s neighbour in Ondiep, an archetypal working-class neighbourhood in Utrecht, the Netherlands, where Hornstra lived between 2004 and 2011.

Kid had a turbulent life: he was banned from seeing his son and struggled with alcohol and drug addiction. In 2013, his body was found floating between two boats in a Utrecht canal. “In the last year of his life, he spent more and more time with drifters and junkies, begging on the street for change,” says Hornstra.

The resulting photobook combines police reports, archival images, and portraits of Kid’s life, taken mostly in his home. “It examines the stigmatisation of the working class while offering a rare insight into the life of a working-class Utrecht boy,” Hornstra explains.

For those of us experiencing extended periods of isolation, the project also takes on a new significance, emphasising the importance of checking in on our neighbours and those in need.

“What emerges is a bewildering picture of Kid’s many personalities, inevitably racing the question: how well do you know the person who lives next door?”

Michael Magers’ intimate project, drawn from his archive of 10 years

The images in Michael Magers’ latest book, Independent Mysteries, are not bound together by time or place, or by any preconceived intention of being shown together. Drawn from a decade’s worth of work made during assignments in places including Japan, Haiti, and Cuba, Magers’ grainy black-and-white images are presented non-linearly with little context. But, there is something that ties them together: a sense of stillness and the feeling that each image has a story. For Magers, they also collectively reveal an emotional pattern — one that existed outside of time or place.

“I was clearly playing out a piece of my own emotional state in my subconscious. I kept seeing the same thing,” says Magers, in an interview with BJP-online. The photographer came across the images around two years ago while sorting through his archives. In between assignments and long-term documentary projects, he discovered photographs of intimate moments, interspersed throughout a decade of his work.

“For a long time, I was really grasping for an emotional connection. Being on the road a lot became an easy way to escape from that; putting the camera between me and experiencing any real intimacy,” says Magers. “Looking back this was the overarching sensation. I kept going back to this idea of being close but far at the same time.”

Gareth Damian Martin’s In-Game photography

Gareth Damian Martin uses photography as a critical tool to analyse game spaces, fusing his background in photography with his work as a games critic. His father was a landscape photographer, which meant that from a young age he was surrounded by cameras and equipment. The experience influenced his perspective when writing and testing games, and led to him launching his own platform in 2017, Heterotopias – a digital zine and website, which employs photography, mapping and writing to analyse game spaces and architecture.

“The desire to capture aesthetically interesting images is what drives me to take a photograph,” says Damian Martin. “But, it is also my belief that the strongest images are those in which their aesthetic qualities do more than offer a pleasing arrangement of objects, and instead tell us something about their subject … This is why I use images as well as writing about games – I don’t believe we can understand or communicate the particular qualities of games and their spaces with words alone.”

John Houck’s iterative and introspective still-lifes

“Your memory isn’t like a file in your hard-drive that stays the same every time you revisit it. It actively changes,” says John Houck, in an interview with BJP-online in 2018. Houck’s images are made by repetitively photographing and rephotographing objects, paintings, and sheets of folded paper, adding and removing elements with each iteration. And, just like our memories, the images can be deceptive — Houck’s works are flat, but they have a tactile quality. “It’s a way to get at the way in which memory is an imaginative act,” he says.

The LA-based image-maker began working in this style while on the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York, where he became captivated by the study of psychoanalysis. Eventually, he decided to go and see an analyst himself, and started to produce images that reflect his psychoanalytic experiences.

Since then, Houck has worked on several bodies of work that reflect on his time in therapy. “I showed up to the first session with a notepad and a pen, thinking I’d make a class out of it – the analyst almost laughed at me. I realised I was using my intellect to separate myself from real emotions, and it changed into something that was much more personal — that I could have never anticipated, it really expanded my work.”

—