Chris Boot: By way of background, can you tell us how you came to live in Tbilisi?

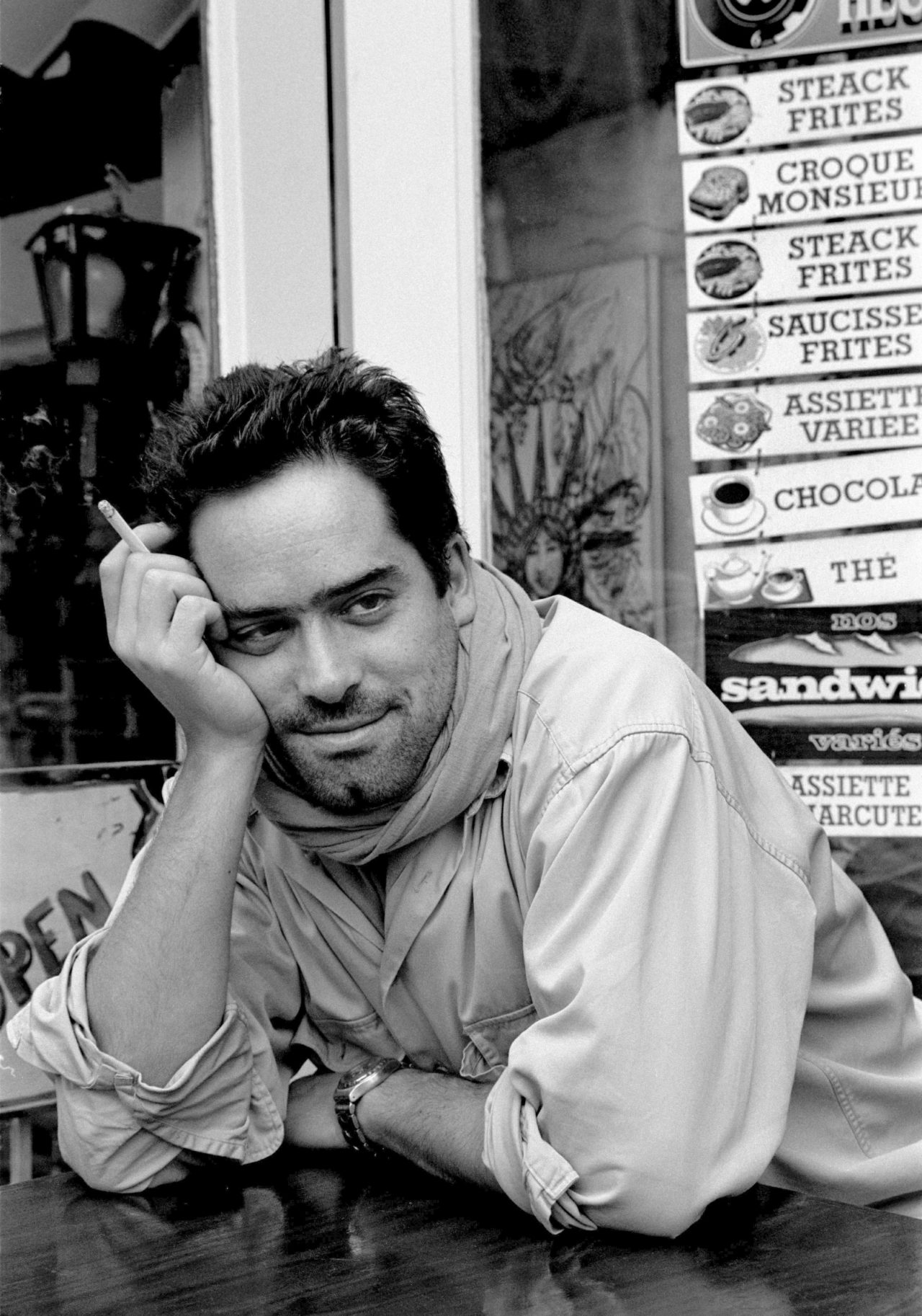

Thomas Dworzak: I got to Georgia by accident in 1993. I was 21 years old, and trying to become a photographer, and so I headed east from Germany, to where things were changing fast. I ended up in Abkhazia, the breakaway separatist republic that had split off from newly independent Georgia in a very bloody civil war that involved the expulsion of 300,000 ethnic Georgians. I was following the story from the Abkhazi side. And then I thought I’d stop in Tbilisi for a couple of months in 1994. I had a university scholarship I was supposed to take up, but by the time September came, I decided to drop my studies and stay in Georgia. I lived there until the end of the 1990s.

The Georgia I first got to know was a totally fucked up failed state. They had a couple of civil wars, and various separatist movements. Abkhazia and South Ossetia had already been snatched by the Russians, who were screwing with them at every turn. There was incredible criminality. The police were criminal, the criminals were criminal, it was one of the most corrupt and criminal places on earth. I think it was the most criminal place on earth. Everything got stolen, including anything metal, and cables, so that meant there were constant power cuts. And everyone stole electricity. If you lived next to a hospital, you could steal electricity from them, but then somebody else would be stealing it from you. Most people lost family members to criminal gangs, there was shooting and robbing all the time. It was never ending.

But the funny thing is that there were so few foreigners there, that everyone was nice to us, and I was safe. I never had any problem. I met a lot of criminals in a lot of situations, but they didn’t touch me. Famously, at that time, someone at the US Embassy gave out a security warning to all Americans in Georgia. There was an intern who came to Tbilisi to study, and he was totally freaked out. He was at my house for a party, and he had with him this doll in a plastic bag. I thought, that’s weird, what’s this 20-year old blond American guy walking around with a baby doll? I asked him. He explained “It’s for security”. Apparently the American Embassy security staff had advised him to carry a baby doll around with him, and talk to the doll while he walked the streets of Tbilisi, in English, so he would out himself as both a foreigner, and a father. And then he’d be safe because criminals respected foreigners and fathers with babies.

CB: And what about the police?

TD: The police were the big issue. They were who you feared most. You would worry about driving, if you were a normal Georgian, because you’d get stopped at a roadblock and the police would fleece you. You wouldn’t report a crime because you weren’t sure if you would be able to pay the bribe to have it investigated. I mostly had to drink my way through all my encounters with the police. Because they were happy to meet a foreigner if you would have a drink with them.

CB: You had to drink your way through road blocks? That’s how you get through?

TD: I got better at drinking, but I would also be trying to take pictures, so in a cheesy foreigner way, I would take a ‘drink bodyguard’ along with me, who was a friend who liked drinking. When I went out I’d ask him to come, and then when we got stopped by police, and we had to drink, my friend would do all the toasts, while I had some story like I had liver sclerosis or something. And he would drink for me! That’s how we’d get through the checkpoint. Ordinary people would just get fleeced. I mean, they killed the deputy head of the CIA at a roadblock in 1993. It was out of control.

CB: Were the police an organised criminal gang?

TD: They were the organised police! At the time you could buy yourself the title of a traffic cop. That was the low end. You buy that and so you’re a traffic cop, and you could stand on the street and you could hold out a stick and stop cars and threaten to confiscate people’s driving license. If you had more money, or your family was able to put more money in, you could buy yourself a procurement job — that was a good job — or an investigator job. Jobs that involved drugs were the best jobs to buy, because you could earn a lot of money taking bribes. There were organised criminal groups who ran the politics and the wars, but the police were the terror of Georgians’ daily lives.