Each year, British Journal of Photography presents its Ones To Watch – a group of emerging image-makers, chosen from hundreds of nominations by international experts. Collectively, they provide a window into where photography is heading, in the eyes of the curators, editors, agents, festival producers and photographers we invited to nominate. Throughout September, BJP-online is sharing their profiles, originally published in issue #7898 of the magazine.

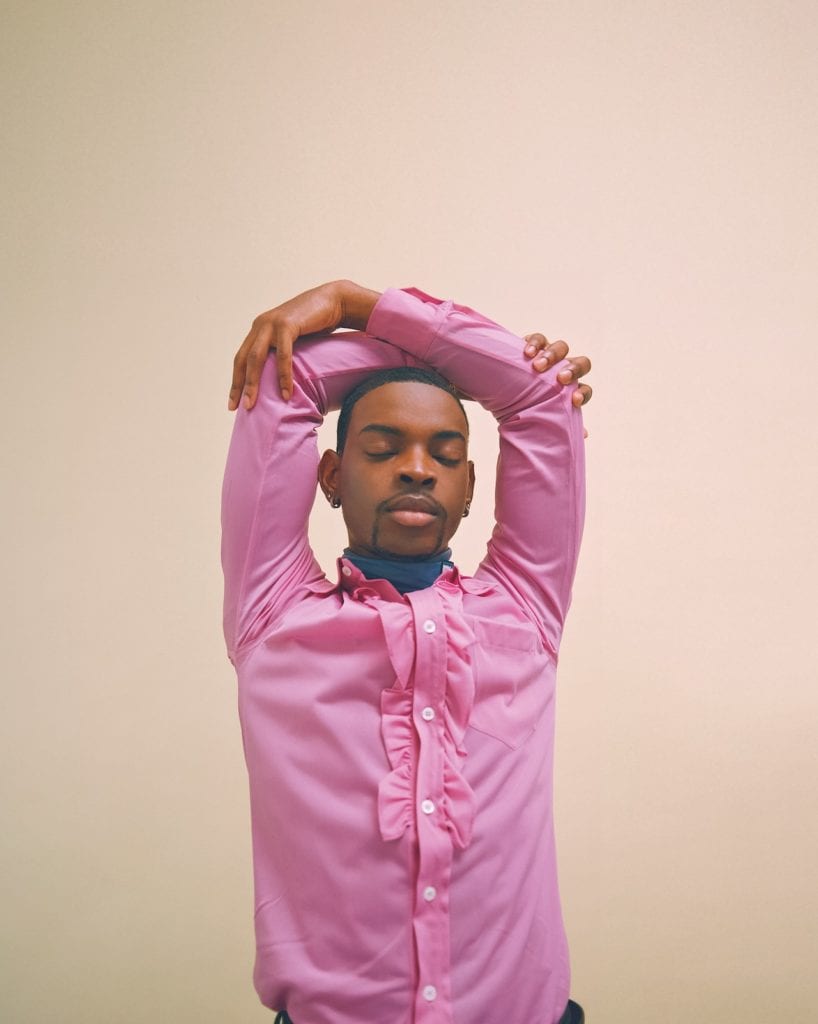

Seen across an impressive array of commissions for the likes of Nike, Burberry, Highsnobeity and Carine Roitfeld’s Fashion Book, 25-year-old Micaiah Carter’s visual universe is not only immediately recognisable – it’s in high demand. His oeuvre harnesses the sensation of blinking in slow motion, absorbing the sun’s warmth while listening to the waterfall tones of crooning vocals. There’s a timelessness in his work – equal parts nostalgia and futurism – that make for an incredibly effective representation of escapism in the present.

For as long as he can remember, photography was part of his life. As the only child of two creative parents, he recalls using a camera to explore his surroundings while growing up. And while posted in Vietnam in his twenties, Carter’s father took a ton of photographs himself, collecting them together into a scrapbook. Packed with personalities, poses, fashion and the hues associated with photographic processes of the 1970s, the impact of his father’s creations are felt throughout Carter’s work, particularly in his personal project titled 95/48, a nod to his and his father’s birth years, which will be released as a book next year.

As a teenager, Carter found a job working at The Daily Press in Apple Valley, his hometown located on the southern edge of California’s Mojave Desert. “The newspaper challenged me to make beautiful images of mundane situations. Not a lot goes on in Apple Valley, so it was interesting to play with a journalistic approach.” By the time he graduated high school, he knew he wanted to go to art school, and in 2013 Carter moved to New York City to attend Parsons School of Design.

It proved a conflicting experience. At the time, discussions about diversity and inclusivity within the photography industry were uncommon. “It wasn’t normal to have tools for Black students to engage with their history, and I didn’t have a Black professor until my senior year. In fact, in my sophomore year I took a course on the history of photography, and we only learned about white photographers. I mean, they probably threw Gordon Parks in there, but it wasn’t until my senior year that I was introduced to resources like Thomas Allen Harris’ film Through a Lens Darkly.”

Despite these limitations in the classroom, Carter started receiving calls from a number of editors who noticed the work he was posting online. In his junior year, he received his first editorial assignment from The New York Times, and also started working with musicians, shooting album covers such as Kimbra’s Primal Heart. When he graduated, Time magazine commissioned him to photograh Spike Lee. “After that, I shot The Weeknd for Time’s international cover, and I kept putting myself out there, working and marketing myself to the people who inspired me. I realised that what I did in front of the camera needed to mean something to me, and that making things feel relatable and personable was what people were looking for.”

That snowball effect has resulted in a remarkable roster of major clients from Samsung and Spotify to Addidas and HBO. But it’s his eye-popping editorials that caught BJP editor Simon Bainbridge’s eyes, including some memorable cover stories, such as Pharell GQ, Megan Thee Stallion for Marie Claire and Playboi Carti for The Fader, all reproduced here. His early success led to his inclusion in Antwaun Sargent’s Aperture exhibition and book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion, seamlessly shifting his work from pop culture media to fine art. Each of Carter’s shoots embody a magical, ethereal setting, but they never feel unnatural, which he attributes to the music on set. “I play a lot of music because it bonds me with the person I am shooting. If I don’t have music, there can never really be a vibe.”

“Black photographers shouldn’t be seen as one-dimensional. We can shoot all types of things. It’s not just about Black photographers shooting Black people; it’s about being open to people’s talents and seeing them as who they are”

Reflecting on the speedy evolution and meaning of his work, Carter explains, “The reason I do this is so that people can see themselves. I think about my nieces and nephews, and how they need representation that goes beyond the stereotypes assigned to Black people. I want to create a wider scope for Blackness, bridging the gap so that everything doesn’t always start with us explaining that we are human.”

Recently, Carter has extended this push for representation by highlighting the industry’s perception Black folks behind the lens. Along with five other photographers, he founded See In Black, a collective of photographers raising funds for Black advancement. Like Sargent’s book with Aperture, the collective highlights how Black photographers have always been here making sensational work—it’s just that not everyone has paid attention. “Of course we want institutions to come to us as a resource if they need a link to a certain photographer who can speak from a certain perspective, but Black photographers shouldn’t be seen as one-dimensional. We can shoot all types of things. It’s not just about Black photographers shooting Black people; it’s about being open to people’s talents and seeing them as who they are.”