Each year, British Journal of Photography presents its Ones To Watch – a group of emerging image-makers, chosen from hundreds of nominations by international experts. Throughout September, BJP-online is sharing their profiles, originally published in issue #7898 of the magazine. Alina Frieske is one of five Ones to Watch selected by British Journal of Photography to exhibit as part of Futures festival, which takes place throughout October.

For the German photographer Alina Frieske, one of the side-effects of lockdown proved vindicatory. “Everything,” she says, “has turned so much more digital: even conversations are on video calls. It felt like you were never really seeing another person”. In her series Unintended Portraits (2018) and Abglanz (2019), Frieske interrogates the uncanny nature of the online images that increasingly mediate our relationship to the world, as well as their sometimes murky relationship to the real.

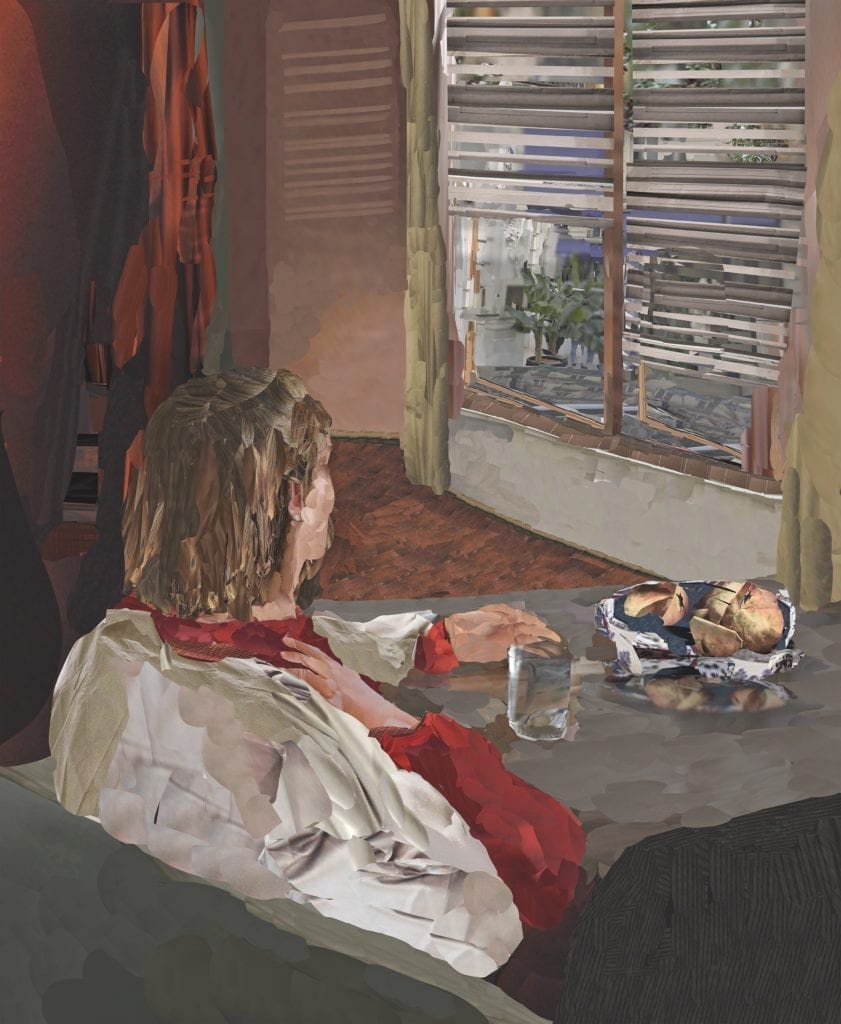

Frieske’s works themselves straddle the borders of reality and artificiality. On first encountering them, you might be forgiven for wondering if they constitute photographs at all. Awash with expressionist whorls and impressionist dapples of colour, they have all the textural thrill of painting. And their subject matter — still lifes, portraits, apartment interiors — draws on the iconography of art history. Only on closer inspection do Frieske’s pieces reveal themselves as prismatic bricolages of photographic fragments. If not strictly photographs, Frieske’s output is intrinsically photographic.

“I would say that I’m working with photographs, which for me is the source of inspiration,” she explains. “I’m also fascinated by the issues around photography, such as the circulation of images.” The rise of digital technologies, and especially social media, has irrevocably transformed the way images are shared and distributed, with huge implications for privacy, performance and presentation. “I’m very interested,” continues Frieske, “in self-presentation as a way of exposure. And also as a way to communicate. We need to produce pictures, almost on a daily basis, in order to show that we’re still active.”

Abglanz, which was completed for Frieske’s MA Photography at ECAL, Switzerland, encapsulates these concerns. It comprises four works, each of which appears to show the same domestic scenario from a different angle. In one, a woman clad in a black sweater looks ahead as if to the camera; we can see a sliver of another person clad in red. In another, this second figure appears in profile, staring towards a partially shuttered window, while we only glimpse the shoulder of her companion. “I was really fascinated,” Frieske explains, “by the number of pictures on social media that repeat.” Abglanz is full of reflective surfaces — a mirror, a glass table, a window — that both magnify the figures and distort their appearance. Shadows and dark spaces suggest unseen presences.

Before attending ECAL, Frieske studied Visual Communication at the Maastricht Academy of Fine Arts, where she acquired a grounding in film, graphic design and illustration. This multiplicity of creative strands continues to inform Frieske’s practice. For her undergraduate project Imagined Recordings (2017), for instance, Frieske concocted a miniature natural history museum, with collaged photographic images alongside sculpture, landscape photography and display vitrines.

That project centred on two zoological pictures, one showing a lobster and the other bird. To create them, Frieske placed a photo of a museum specimen in Google’s reverse image search. “I wanted to see what the algorithm would detect in a picture that it doesn’t really know,” she explains. “It was fascinating to see how well it normally worked, but then I found some pictures where it had some difficulties.” Her photographs of the lobster, for instance, dredged up some images of plants, and the resultant work features mossy snatches of greenery. “It’s a kind of conversation,” Frieske continues, “between how the algorithm understands my pictures, and me attempting to reincarnate the species.”

The method of creating Abglanz — named for a German term meaning ‘distant echo’ or ‘pale reflection’ — also bridged the gap between digital and analogue. “I start,” Frieske explains, “with a blank page. I do sketches and drawings, and I imagine what I’m going to present. Then, I bring it onto the computer.” Frieske builds up a “little encyclopaedia” of photos from social media. “I use little fragments,” she continues, “so it’s not about one person anymore, and bring them into the outlines I’ve drawn. Once the forms are developing, I print the picture again and rephotograph it.” This researching, photographing and collaging continues until Frieske reaches the final image, a process which can take weeks.

Now based in Berlin, Frieske, who was nominated by Bruno Ceschel of Self Publish Be Happy, is compiling a book related to Abglanz, which will enumerate her methods. “It can be seen as a kind of formula for how the pictures are brought together,” she says. She also intends to investigate possibilities beyond two-dimensions. “The work I’m doing now,” Frieske continues, “is really an attempt to go more into sculptural representation, to see the potential of combining the mediums.” Wherever Frieske goes, it seems likely that she will continue to push at the boundaries of what photography can be.