Robert Mapplethorpe tried his hand at a startlingly extensive range of artistic forms over the course of his 20-year career – from sculpture and drawing to collage and construction – but it was photography, the most instantaneous and intimate of all those he employed, which he found best suited his needs. Now, following the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and neighbouring J Paul Getty Museum’s acquisition of the vast body of work he created in the 1970s and ’80s, the two institutions hold complementary retrospective presentations, together titled Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium (showing mid-March to the end of July) to highlight different aspects of his oeuvre.

The show, which will tour to Montreal, Sydney and beyond, takes as its underlying theme the ‘inherent dualities’ that characterised Mapplethorpe’s practice, explains Britt Salvesen, LACMA’s head of photography and the curator of the exhibition. “He seemed to enjoy playing with those contrasts between his downtown reputation as a rebel and a provocateur, and his uptown reputation as a maker of beautiful society portraits and floral still lifes. We took that as a point of departure.”

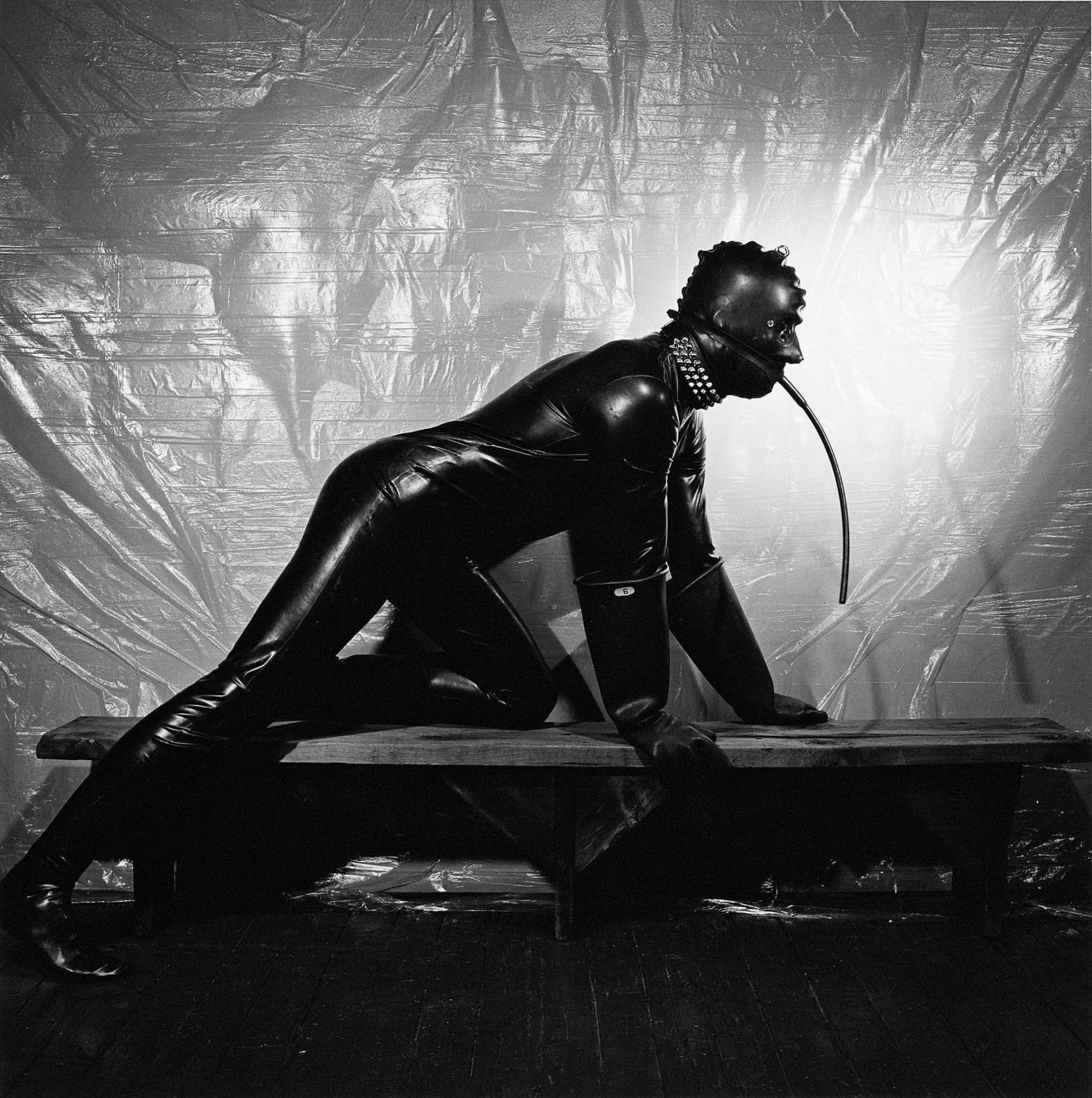

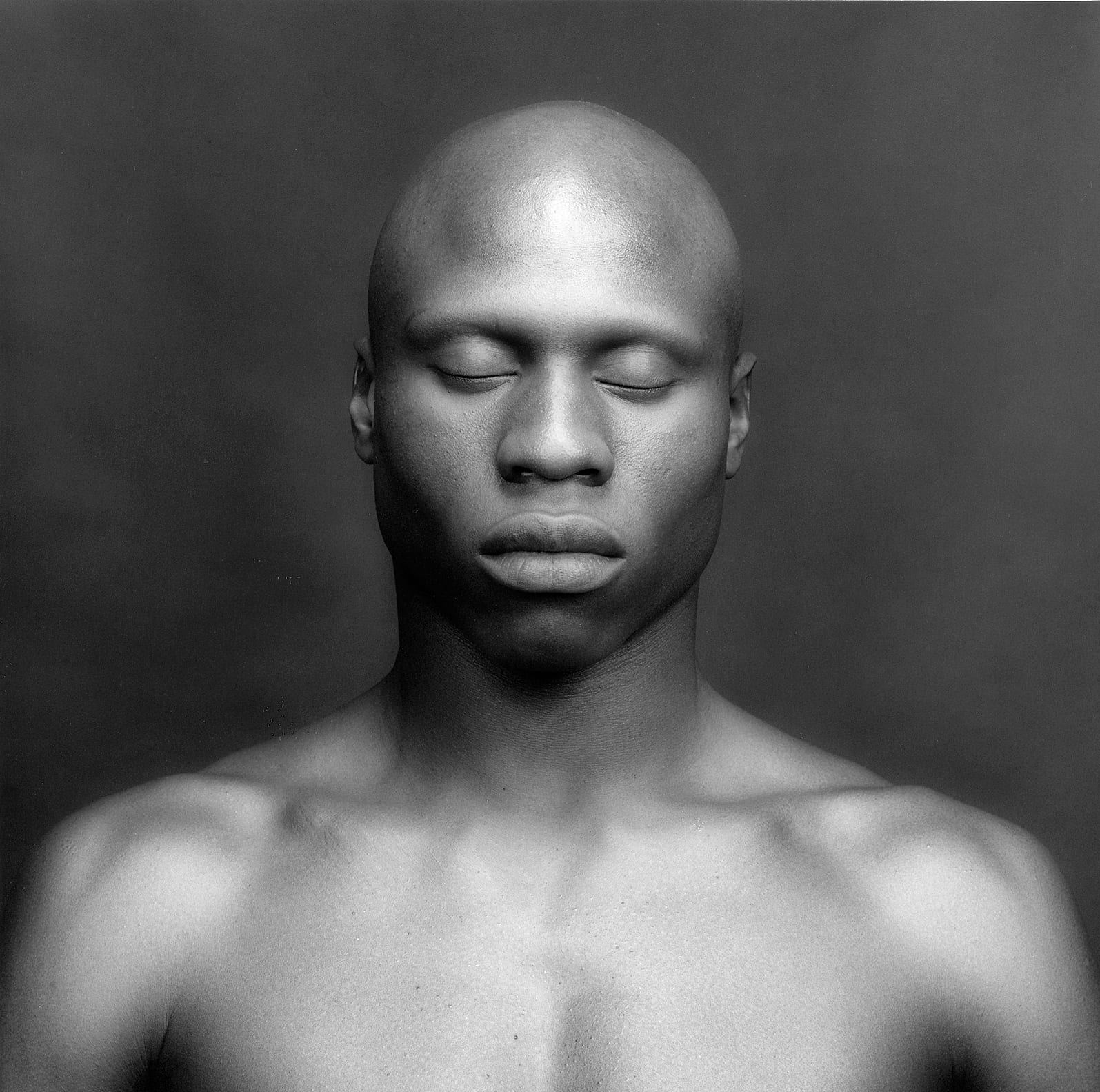

This parallel presence of high and low occur throughout Mapplethorpe’s work. “For instance, some of his figure studies are emulating classical sculpture – they’re completely elegant and timeless,” Salvesen continues. “Others are more a document of S&M activity, very contemporary and raw. So he really worked across a whole range of traditional art historical subjects.”

Set against the backdrop of Aids-related paranoia, the more sexually explicit of Mapplethorpe’s spectrum of subjects, and the frank homoeroticism he portrayed, made him a target for the religious right in America in the late 1980s. Exhibitions were censored, but ultimately the notoriety bought him a wider audience and served his value in the art market. And yet, until the 2010 publication of Patti Smith’s award-winning autobiography, Just Kids, the fervent battles of the age, and his own early death from Aids in 1989, seem to have overshadowed his work.

“[Smith] really created a human character that people really responded to,” says Salvesen. “In a way it was a long overdue corrective to the associations of him with sensationalism and scandal that came from the early ’90s culture wars here in the US. He was demonised for the explicit content of his work.”

The revival of interest in his work over the past five years created a new curatorial challenge for LACMA, which chose to focus on the profound role Mapplethorpe played in asserting photography within contemporary art of the time. “He didn’t want to remain in a photography specific context, where you typically had smaller prints and more of a snapshot aesthetic, so he was observing that and setting himself apart from that,” Salvesen says. In her opinion he succeeded in this “by moving to galleries that were not specialist in photography, but dealt in other contemporary art”.

This idea is similarly validated by the pop-cultural presence Mapplethorpe has today, which is due in part, Salvesen suggests, to the unmistakable visual language of his images. “You can’t mistake a Mapplethorpe for anyone else,” says Salvesen. “I find that really interesting because you could think about a floral still life or a black-and-white portrait as being quite a generic thing. In a way, it’s easier to think about Mapplethorpe in context to the slightly older figures of his time, say, Richard Avedon or Irving Penn.”

The result is an exhibition in which the artistic and sexual undergrounds of 1970s and ’80s New York will collide with compelling aplomb. “Mapplethorpe was really obsessed with the idea of perfection, and obtaining it while also knowing that was never possible. He talked about photography as the perfect medium for him and for that moment in the 1970s and ’80s, because it allowed him to work quickly, and move on to something else. He was always curious about the next challenge.

“Of course he knew he was pushing boundaries, but he felt that’s what art should be doing. That borderline between pornography and art, specifically, was one he really challenged viewers to overcome. And in a more art historical way, the borderline between photography and art came along with that.”

www.getty.edu

www.lacma.org

First published in the March 2016 issue.