If you don’t get the reference, it’s a curious title for a photobook – Fables of Faubus, the 30-year retrospective by British documentary photographer Paul Reas. But if you’re a jazz fan you’ll know it’s taken from a song by Charles Mingus, written after Arkansas governor Orval Faubus decided to bar the integration of Little Rock Central High School in 1957.

To Mingus, and many others, Faubus stood for a dark force holding back progressive social change. For Reas, the title suggests the metanarrative that runs behind the many stories he’s shot in the UK on heavy industry, consumer culture, the heritage industry, and more – namely, the disenfranchisement of the British working class, “the years of decline of industry and the fall out from that, communities being de-centred and levelled”. As Reas told the Bradford Telegraph & Argus: “I would say I photograph people but I think the pictures are more about systems people find themselves in.”

And it’s a process he sees at work on his own life too, because Reas was born into a working class family in Bradford, a Northern city that boomed in Britain’s industrial heyday but suffered heavy decline after its loss. Leaving school at the age of 15, he trained as a bricklayer for five years, before leaving to study documentary photography at the Newport College, Wales in 1982.

It sounds like an unusual trajectory and in many ways it is – Reas is clearly a singular man, with considerable visual acuity and the sheer grit needed to make it in photography. But, as both his photographs and the texts that accompany them in Fables of Faubus make clear, he’s also keenly aware of the wider forces that shape our lives – including his own. “It’s something I think about a lot,” he tells me. “The circumstances people find themselves in, how I’ve found myself.”

As such, while Fables of Faubus tells the story of the British working class over the last 30 years, it also tells the story of Reas’s own journey – in particular his journey through photography, via the stories he shot, the influences he absorbed or rejected, and the projects he engaged with, personal, editorial and commercial. His work is presented chronologically, story by story, but introductions to each series lay out both the social and economic context for the photographs, and Reas’ reasons for shooting them.

“I was keen to reflect on what I had done and how the dots joined up, and find a common theme,” he tells me. “When I look back I can see the connections. I say to students that as a photographer, although you’re photographing other things, actually you’re only photographing your own life and your own experience. That’s been the case with my work, I’ve been preoccupied with my own origins and background. I’ve photographed a lot of working class communities – it’s my background and, although my circumstances have changed, it’s where my interests lie.”

Dyslexic, Reas struggled at school but he found a passion for music early on – initially for Northern Soul, the music and dance phenomenon in Northern England in the 1960s and 70s, in which predominantly white, working class youngsters sought out fast, raw soul music from independent American labels. Reas visited Manchester’s legendary Twisted Wheel club when he was just 13 but says he was always too shy to join with the dancing, preferring to sit on the sidelines and watch. Maybe this experience developed his interest in observing, though he says he was “always able to express myself visually”. What lead him more directly to photography was the lyrics of this music, which were rooted in the experience of black America and the burgeoning civil rights movement.

“Something in it really connected with me because I could see the connection with class discrimination in the UK, which I experienced in everyday life,” he says. “Because of that I started to read more around civil rights, and through that I discovered books with photographs. Through music I became more and more obsessed with photography, to the point where I thought I would go to study it.”

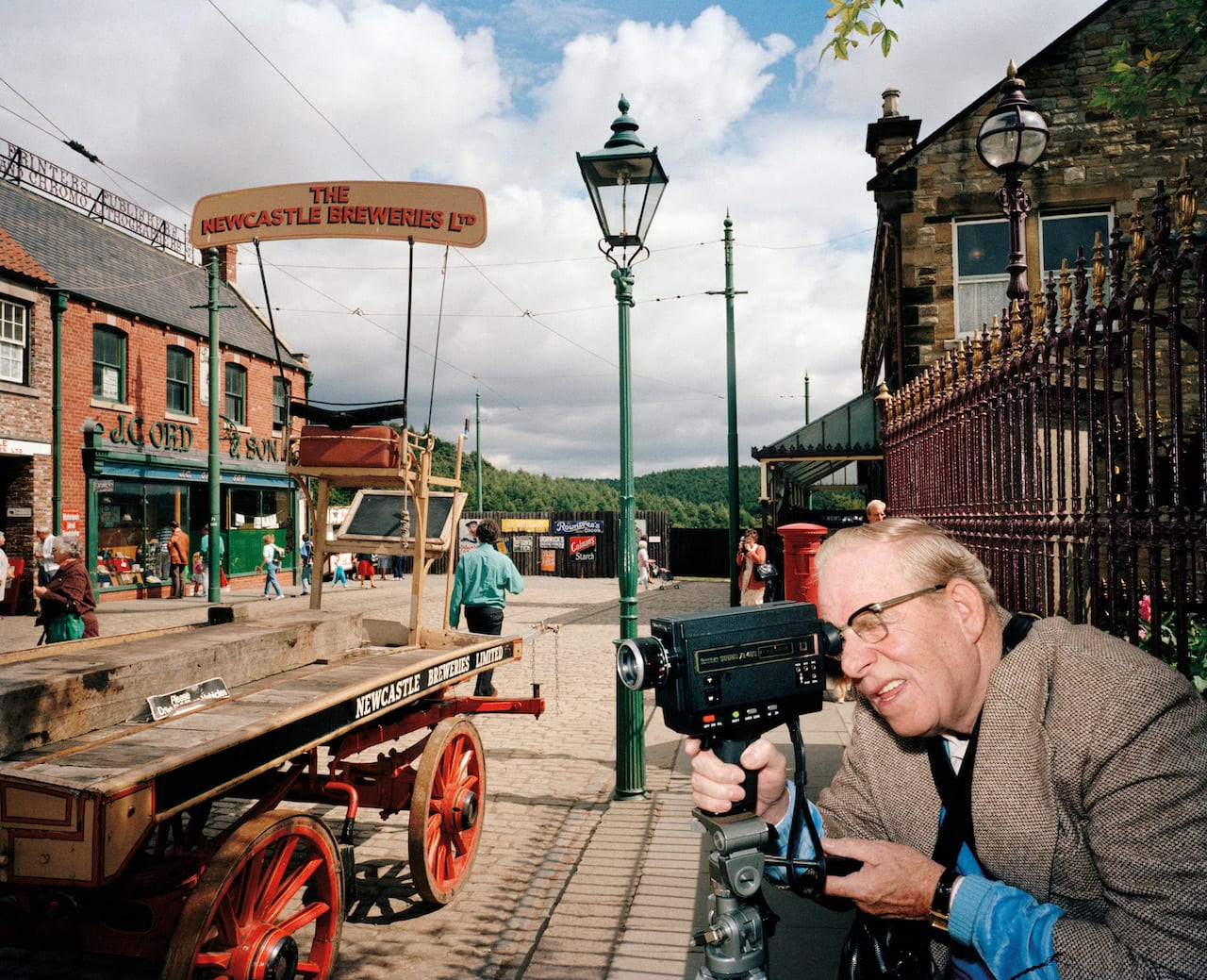

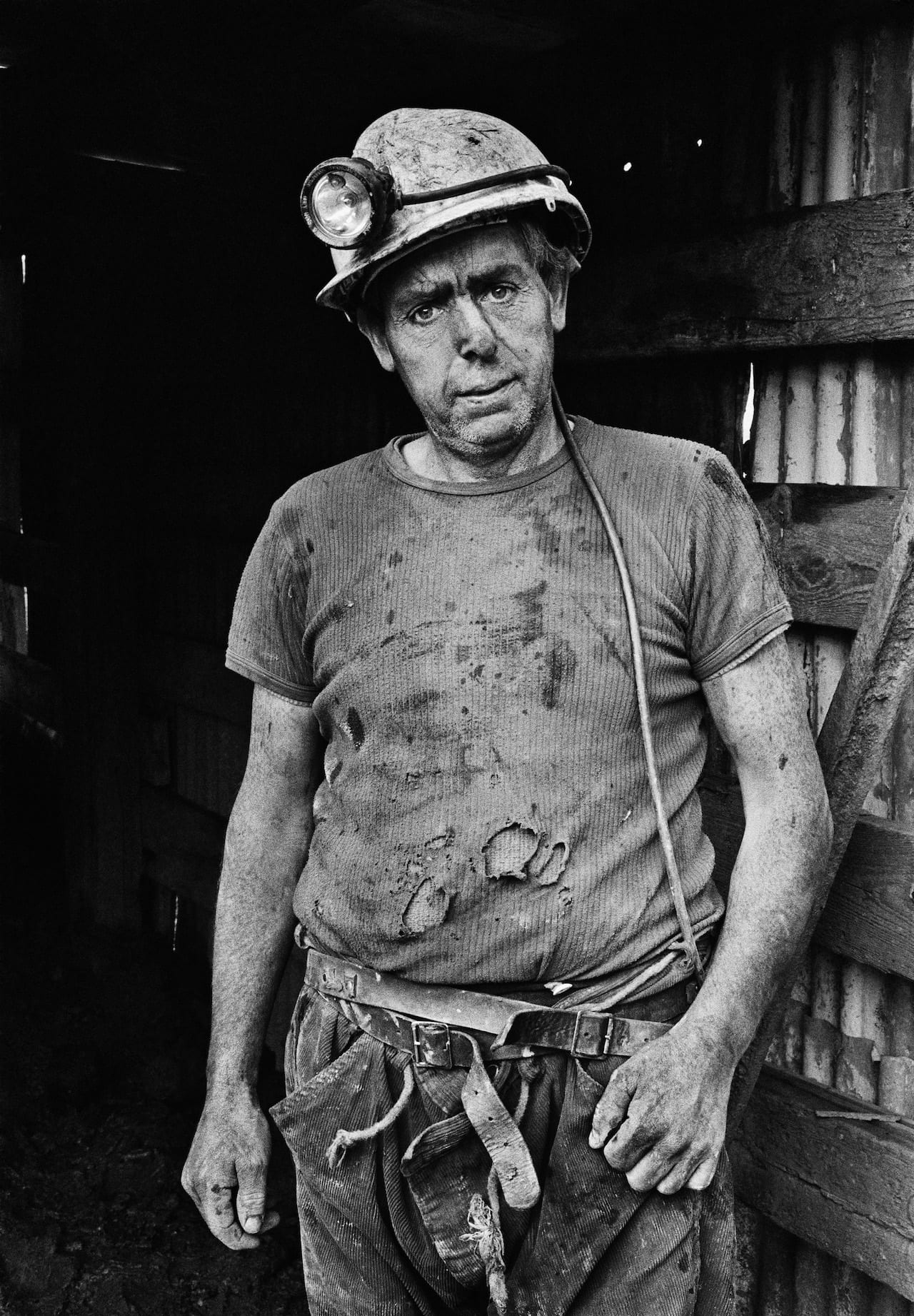

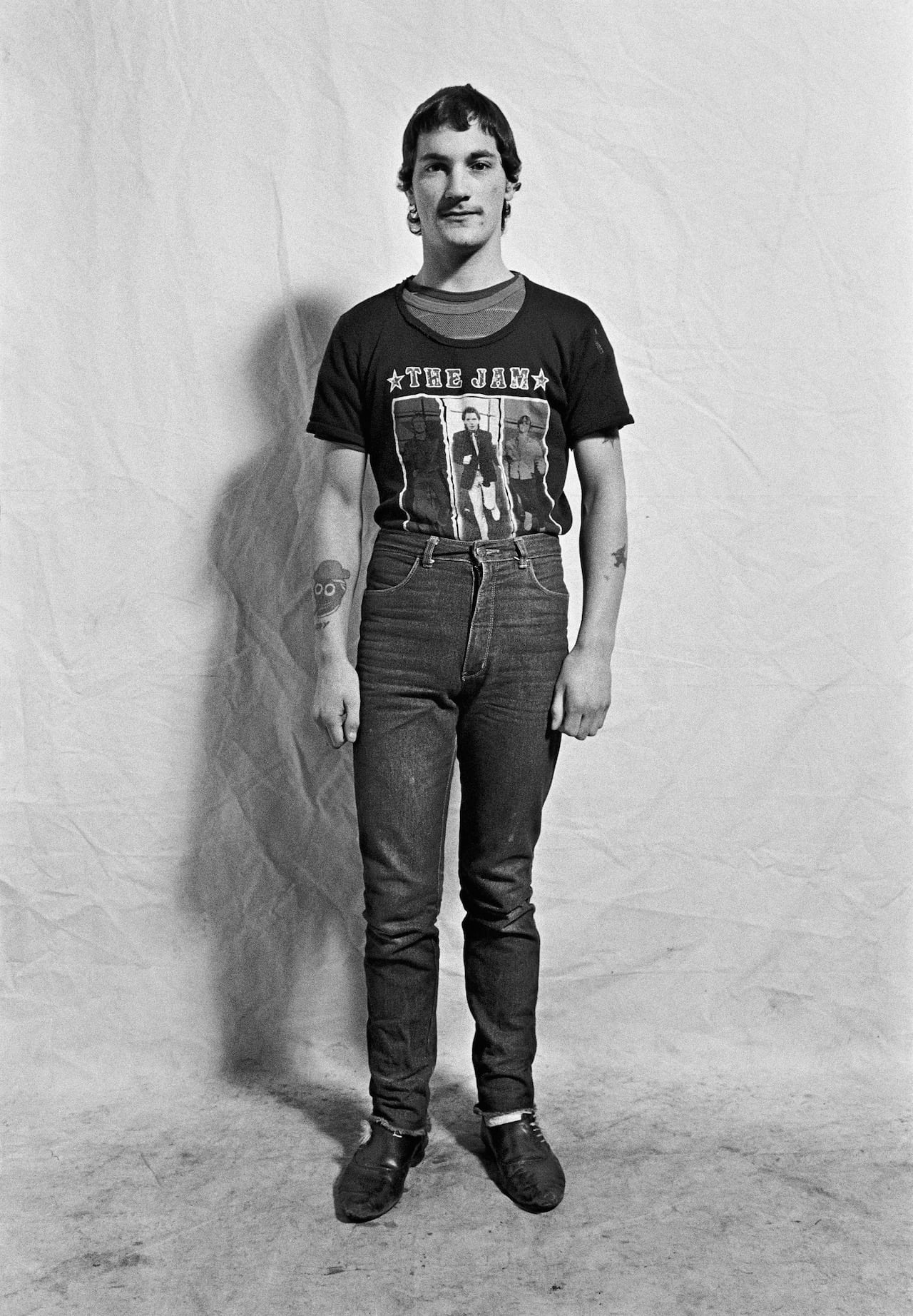

As he points out in Fables of Faubus, black-and-white documentary images proved his first big influence in photography, and his early work on heavy industry – shot in South Wales while he was still a student – clearly shows its impact. Reas is proud enough of this work to include it in the book, but he also gently undercuts it, commenting on the tendency of British documentary photography at the time to focus on “the preservation of ways of life which were under threat of change, or photographers were drawn to the quaint and whimsical”, and adding that “this was a tendency I would deliberately resist in later projects”.

He also points out the impact that August Sander’s work had had on him though, “not only by the scale of his endeavour, but also by the grace, beauty and dignity he bestowed upon his subjects”. He shot many portraits of the men at work in South Wales, from full body shots of them holding the tools of their trade, to close-up images of their faces. “My portraits were a poor attempt at trying to get close to some of the majesty of Sander,” he comments.

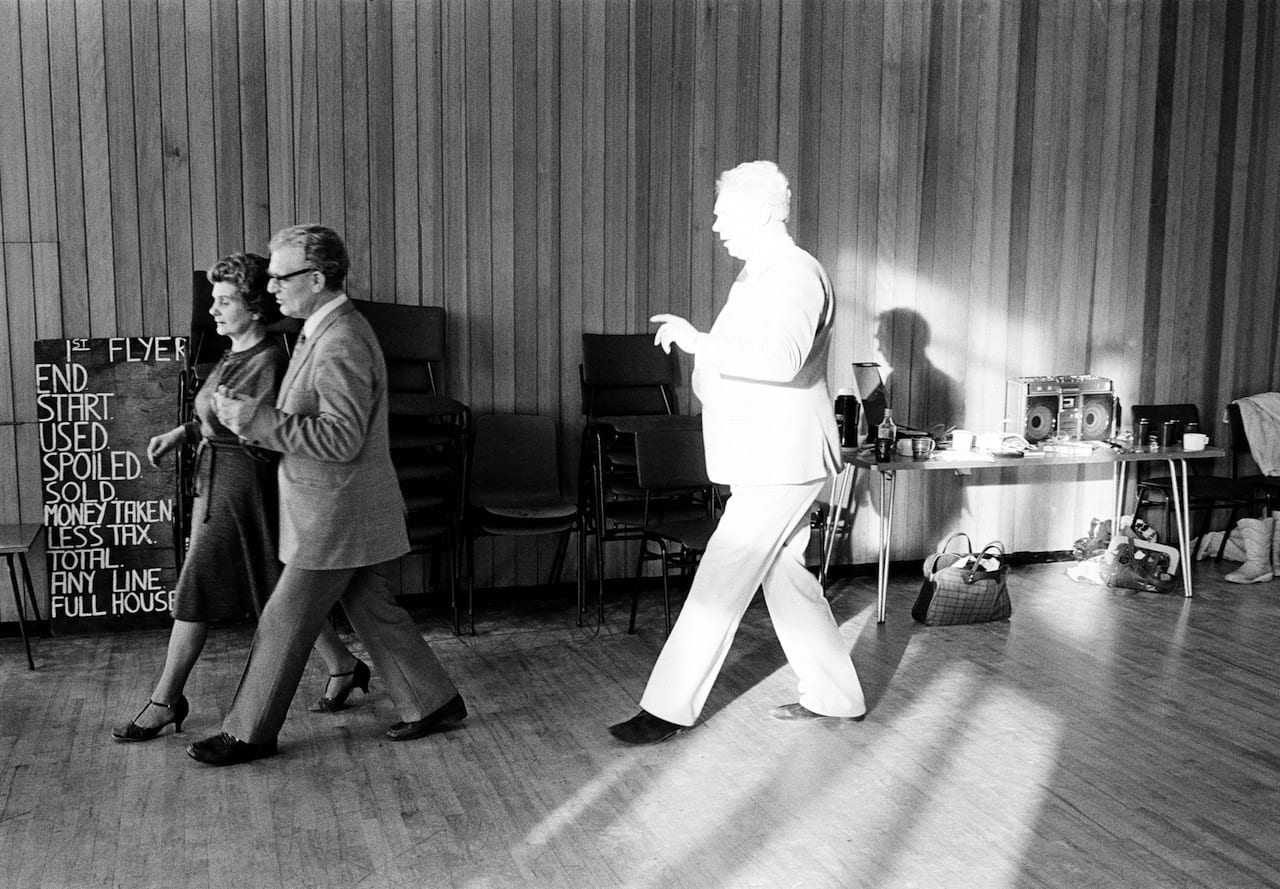

But Fables of Faubus next includes an essay by David Chandler, picking out just one of Reas’ shots. Shot in 1984 in a community centre on Penrhys Estate, South Wales, it shows a man in a white suit at a dance class, caught in a shaft of sunlight and made other-worldly by it. As Chandler tells it, Reas’s tutor Martin Parr picked out this shot from many other, more traditional images Reas had taken that day because of its potential to move beyond “the former realist tradition to conjure an ambiguous, illusory drama from the everyday narrative unfolding in the room”.

It was to prove a turning point, encouraging Reas to move towards a new way of seeing. Becoming interested in the potential of colour photography to illustrate the new circumstances of post-industrial communities, he started shooting in colour, creating the series that would become I Can Help – a lurid, often funny vision of the consumerism breathed into life by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

“Buoyed by her defeat of the miners, victory in the Falklands War of 1982 and the survival of an assassination attempt in 1984, Margaret Thatcher increasingly saw herself as invincible and on the right side of history,” writes Reas in his introduction to these images. “Her neoliberal policies, faith in a free market economy and a firm belief in individualism turned British culture from a ‘we’ to a ‘me’ generation.

“The deregulation of the banking system meant that credit was easy to come by and consumer spending was rising fast. This growth in consumption was becoming more and more evident in Britain in the mid-1980s. The then-new shopping malls, situated on the edges of cities, were the new cathedrals of consumption, and the new ‘retail parks’, with their supermarkets and furniture stores, were the parish churches. Shopping and the purchasing of an off-the-shelf lifestyle were becoming new leisure activities.”

I Can Help was published as a book in 1988, and that and Reas’ next book – an equally dark depiction of the heritage industry titled Flogging a Dead Horse, published in 1993 – helped establish him as part of the new wave of British documentarists, alongside image-makers such as Martin Parr, Paul Graham, and Anna Fox. Using colour, they shot often satirical images of contemporary Britain, inspired by “a disillusionment with the way documentary looked at that time,” says Reas.

“There was a real tendency to look for the esoteric or exotic – not being made in Britain about Britain and the stuff that was being made in Britain was of a particular type, there was a tendency to fix people and communities in aspic, to freeze them in time,” he tells me. “It was a decision in my case, and I know for other photographers, to address this and try to do something was more about peoples’ actual lives in a way that was more spiky and edgy and even more difficult to look at.”

The “difficult to look at” is a moot point, because detractors argued that this work tipped over into poking fun at its subjects. Martin Parr, for example, faced a barrage of criticism when he published The Last Resort in 1986, for what some saw as his mockery of the working class holiday makers he depicted. [Henri Cartier-Bresson apparently told Parr he was “from a different planet”; Parr apparently replied: “I know what you mean, but why shoot the messenger?”]

“It was a criticism levelled at all of us working in the new colour way in the 1980s,” says Reas. “We were very consciously using irony and humour and satire – they are visibly in my work, there is a tension there. But taking the piss? I hope I’m not, it’s not part of my intention. I was just reflecting the circumstances people found themselves in, in a way that was sometimes a bit unpalatable.”

And while it may have been unpalatable with the old guard, the new look proved popular with picture editors and advertisers, which meant that throughout the 1990s, Reas was kept busy with commissions. In his book he comes across as a little critical of this period, commenting that he “became further and further removed from the independent world of photography which had given me so much” and that he “lost contact with photographers who were friends and whose work I respected”.

But speaking with me he says he’s proud to have put this new take on documentary photography into the wider culture, and to have had a career that straddled the commercial, editorial and art worlds – especially as in those days, as he puts it, “you usually had to decide to do one or the other”.

Some of these images are included in Fables of Faubus, alongside an essay by Val Williams, in the context of the spreads or ads in which they appeared – there are a fantastic couple of shots from Centre Parcs which were shot for The Sunday Times in 1990, for example, showing people seemingly adrift in their hermetically-sealed holiday environment. There’s also a humorous shot for Fujicolor, showing a glum lady holding a horse which apparently has two bodies.

The last set of pictures in the book are Reas’ shots of Elephant and Castle, though, which were taken in 2012 and show passersby caught walking through the London area’s bustling market – a community under threat from developers, as rocketing property prices encourage them to build high-end apartments where social housing once stood. “As with many projects I have undertaken, there was a personal connection,” writes Reas.

“The area of the Elephant and Castle was the home to one of London’s longest-established working-class communities, who were being ‘decanted’, to use the developers’ jargon, from their council properties to clear the way for the construction of luxury apartments. At the same time my parents were being forced to leave the house in which I was born, the one which had been the family home for over fifty years, because the council had sold this particular area of the estate in Bradford to a private developer.”

Fables of Faubus has been a long time in the making, but Reas says that doing so has been a pleasure. Looking back he’s confident he’s “made a contribution” he says, both in terms of his own photography and in his work at Newport – where he’s now course director of the documentary photography course he once studied on, still one of the best-respected courses in the UK, and the alma mater of interesting emerging photographers such as Lua Ribeira, who’s a Magnum nominee, and Guy Martin, who’s also just publishing a book with GOST.

He’s particularly proud of have played a part “however small” in the new colour documentary movement, “which was really interesting and impactful, and did change where British photography was headed”. And while he knows that there’s a “surface level of interest” in his older photographs, in terms of nostalgia or sheer curiosity about fashions from back in the day, he also hopes that his images have retained their edge.

“Obviously hopefully they are still pertinent as political statements as well,” he says. “Hopefully that is sustained. Of course it’s hard for graduates who didn’t grow up under Thatcher to connect with that, and with what that was all about. But hopefully together my work still has some meaning, and some meaning to the younger generation.”

Fables of Faubus is published by GOST, priced £35 https://www.gostbooks.com/product/fables-of-faubus-2/

Paul Reas will be signing advance copies of Fables of Faubus on 09 November on the James Hyman stand at Paris Photo at 13.00, and on the GOST Books stand at Polycopies at 17.00 www.parisphoto.com www.polycopies.net