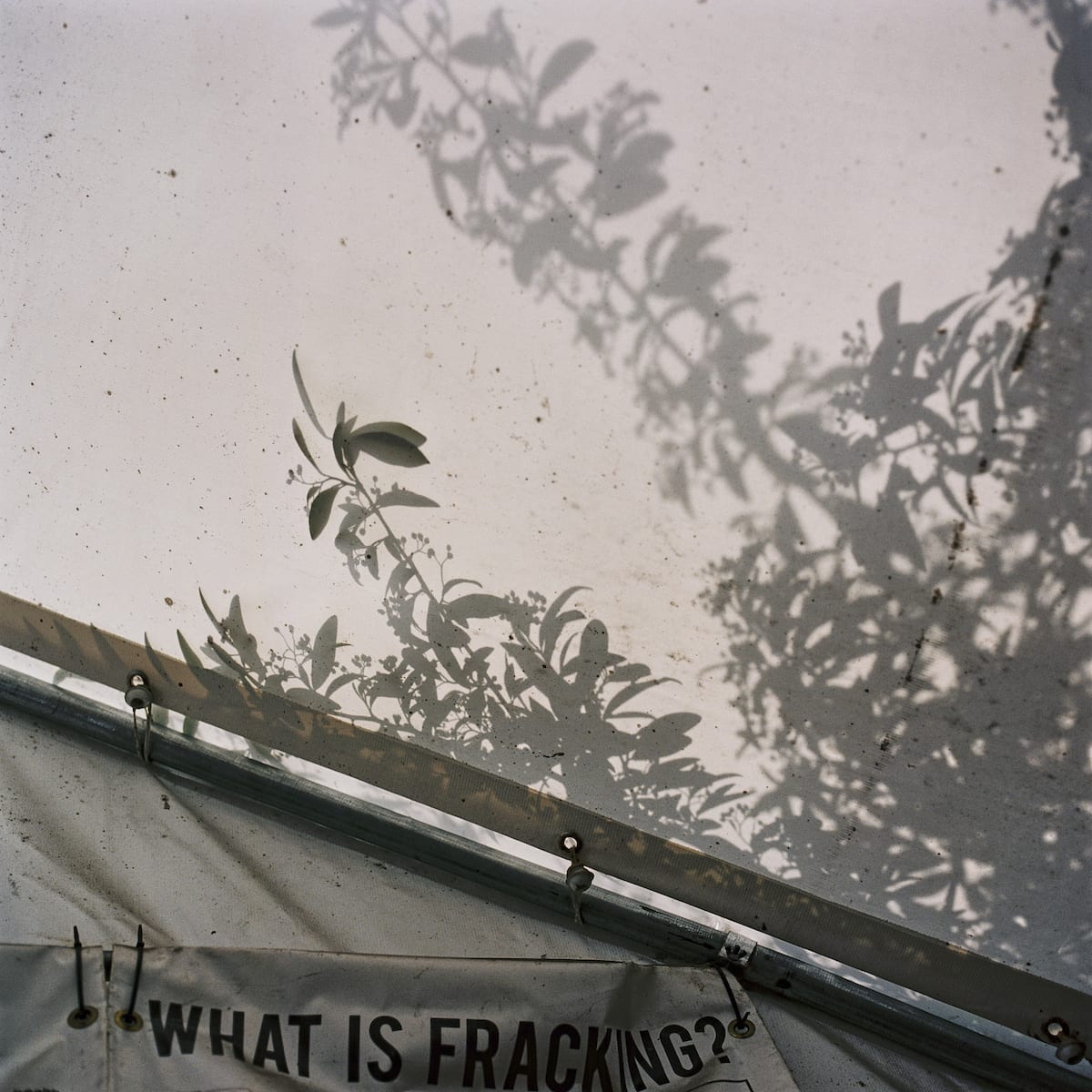

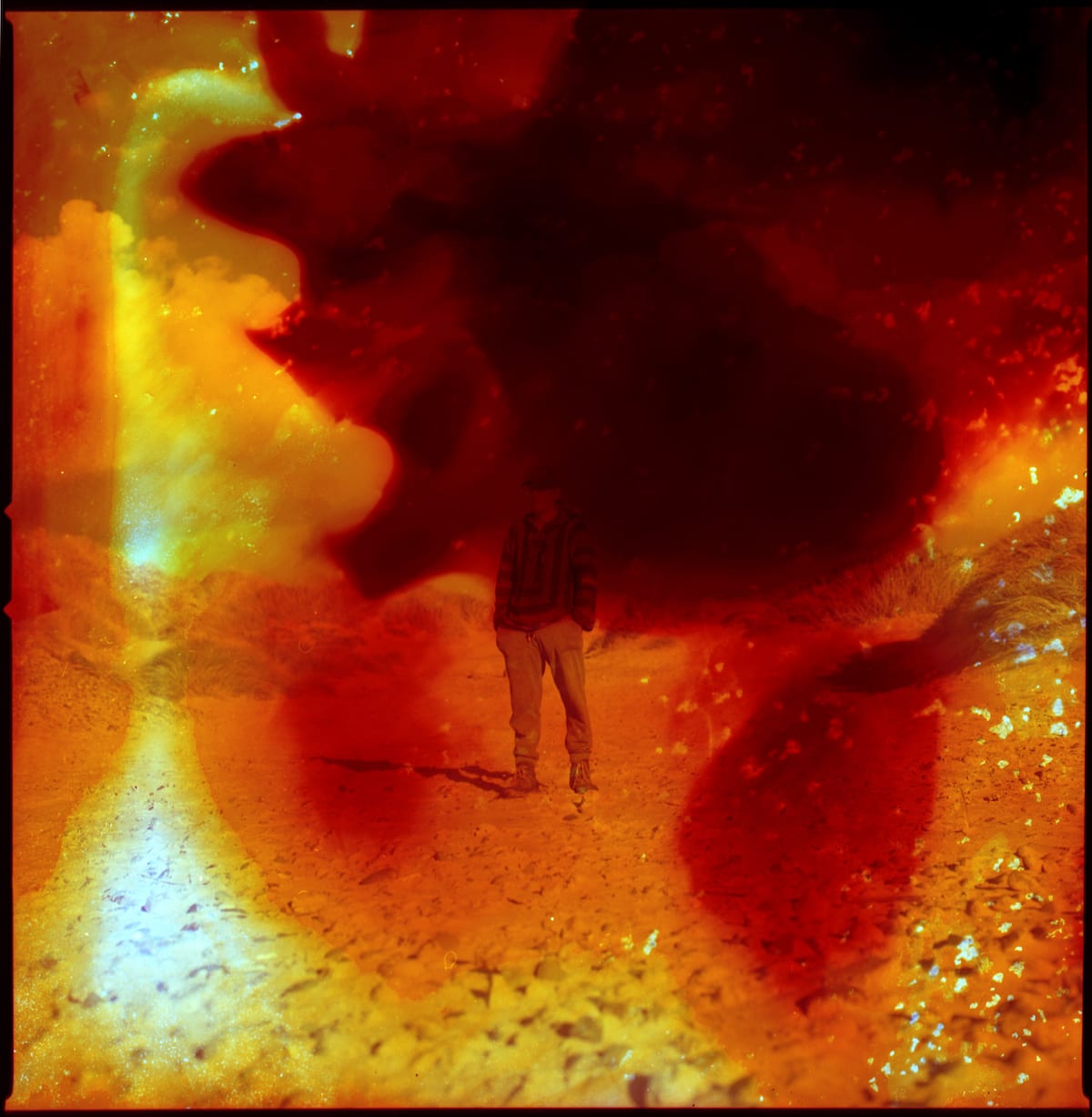

For Fractured Stories, a British Journal of Photography commission supported by Ecotricity, Rhiannon Adam takes us inside the fracking debate. A series of editorials published on BJP-online tell the stories of the individuals she encountered. A number of images are corrupted with a constituent chemical of frack-fluid, alluding to the potential environmental impacts of the practice. The first in the series tells the stories of the protectors resident at the two permanent protest camps alongside the Preston New Road fracking site.

“It is going to be a beautiful sunset,” says Tiga. A wall of sun-dappled sand dunes rise up behind him; the Irish Sea stretches out in front.

“If you choose to present things in an alternative way they tell a different story,” explains Rhiannon Adam, as she photographs Tiga, an environmental activist on the beach of Lytham St Anne’s, a seaside resort in Lancashire. Back at New Hope Resistance Camp, the nearby protest camp where Tiga lives, there is a sense of unease. But here, peace reigns, momentarily.

For the past four months, Adam has lived and worked among a community of campaigners, of which Tiga is part, at two permanent protest camps. Both New Hope Resistance Camp and Maple Farm Camp sit alongside a fracking site at Preston New Road in Lancashire. “I wanted to understand the complexities of the situation,” she explains. “It was important that I was able to detect the change of mood and all the things that they are so sensitive too. To be aware of those and go with the flow; to ride the emotion of it.” For Adam, listening to an individual’s story dictates how she photographs them. Her ultimate aim: to redirect the narrative away from the singular news piece and give an identity to those involved.

In the UK, fracking first came to national attention in the spring of 2011 when Cuadrilla Resources fracked at a site in Preese Hall in Lancashire. Two earthquakes were detected and a moratorium on the practice was enforced. This was lifted in late 2012 after the UK Government introduced a new regulatory regime geared toward monitoring and reducing seismic risk. Located midway between Preston and Blackpool, Preston New Road became the focal point of the fracking debate after Cuadrilla applied to drill at the site in 2014. The UK government gave the final go-ahead this summer and fracking took place for the first time on 15 October 2018, midway through Adam’s project. The process has caused numerous tremors to date. A minor earthquake that occurred on Tuesday 11 December 2018, when Cuadrilla resumed fracking after a one month break, was far higher than the government’s regulatory threshold and on par with the tremor that led to a moratorium on the practice in 2011.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, as it is more commonly known, is a controversial process used to extract oil and gas trapped in shale, and other, rock formations. It involves drilling down deep into the earth; a mixture of water, sand and chemicals is then injected at high pressure to fracture the rock. The gas released travels into the water stream and either flows back, or is pumped, to the surface.

Fracking is more common in the US where it has revolutionised the energy landscape: over 100,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled and fracked in the country since 2005. Despite Europe being projected as the new fracking mecca, it has been largely unsuccessful. The process is not permitted in France, Germany or Bulgaria; Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have all placed their own suspensions on it.

In the UK, fracking first came to national attention in the spring of 2011 when Cuadrilla fracked at a site in Preese Hall in Weeton, Lancashire, causing earthquakes; a moratorium was subsequently imposed until late 2012. Public opposition resurfaced in 2013 as protests sprang up around a proposed site near the West Sussex village of Balcombe and the drilling of a well at Barton Moss, Salford. Preston New Road became the focal point of the fracking debate after Cuadrilla applied to drill there in 2014.

Opponents stress the potential environmental impacts: earthquakes, pollution of water supplies, water wastage and air pollution. Other concerns include, noise pollution, the industrialisation of the countryside and a detrimental effect on house prices. Ultimately, it represents a continued investment in fossil fuels at a time when eliminating our reliance on them is crucial.

Advocates for the practice point to its potential for job creation, along with its ability to offer us energy security and act as a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future.

At New Hope and Maple Farm a dedicated community of protesters, or protectors as they prefer to be known, have worked to monitor and impede Cuadrilla’s progress. Almost directly opposite the site’s main gate, protectors keep a 24/7 vigil from a small shed, known as “Gate Camp”, papered in tinfoil with a wood-burning stove at its centre. Locals, along with campaigners from elsewhere, also lend a hand. From here, the group monitor and observe the site: from the coming and going of vehicles, to the number of pipes going down the well. Each observation is meticulously recorded in a log book.

A range of other protest tactics are also employed. Many participate in direct action. Lock-ons are common. For these, participants attach themselves to something with devices constructed from a range of materials including plastic and concrete. “We try not to release ourselves and the police try everything they can to make us release ourselves; although, as of yet, they have not tried tickling or spiders,” explains Jag, a resident of New Hope. Another tactic involves walking and running in front of vehicles, or climbing on top. In summer 2018, in an attempt to prevent such actions, Cuadrilla took out an injunction, which forbids trespass on the site and surrounding farmland. Campaigners have continued regardless.

The camps themselves are not what one would necessarily expect: neat, organised and, for the most part, peaceful. Through the gates of Maple Farm, the more family orientated of the two, a gravelled courtyard, bordered by trees and shrubs, gives way to a cluster of caravans. A polytunnel, rammed with chairs, tables and protest paraphernalia sits at the centre. Directly opposite, the residents have erected a walled-gazebo, in which communal meals are cooked and served. The courtyard exists as a community hub for both resident protectors and campaigners from elsewhere.

Then, further down, towards Preston, a smaller entrance, concealed by hedgerow, opens onto New Hope. Here, a melange of shacks, assembled from mismatched materials, lie spread out across the ground. “New Hope is self-sufficient,” says Tiga. “We have a log burner, boiler and solar water-system that heats water up. We built everything with recycled equipment and when we leave we will take it all down and reuse it again.”

Both Maple Farm and New Hope occupy the land of local businesses who support the activities of the protectors. The former takes its name from the plant nursery of John Toothill, upon which it sits. The latter has spread out across the backyard of Lytham Windows. “It is a big sacrifice because it is a main road site, which, from a business point of view, is an important location,” says Toothill, who is heavily involved in the protests against Cuadrilla, “but I am happy that it is being used to further the campaign against this harmful process.”

Below, Adam’s images tell the stories of the protectors she lived and worked amongst:

–

Kai and Callum

“When you do a 12 hour night shift at Gate Camp you have to keep yourself awake somehow; I try and read my books for university”

Kai, 20, and Callum, 22, are a couple who met at Maple Farm Camp. “I was doing a photo project during the summer when I stumbled across this,” says Kai, gesturing to Callum. “I thought, ‘he is nice to take pictures of.’” The two now share a tent in Maple Farm’s backfield.

Every Wednesday the couple take the night shift at Gate Camp; for 12 hours they sit and monitor Cuadrilla’s activities in and out of the main gate. Kai is studying a BA in Photography at Blackpool and the Fylde College and stays awake by reading. “When I was by myself I used to get panicky with my coursework: topics and big words that I did not understand,” she says. “But, living in this community, I can just ask someone and chat through it. I find it a lot easier.”

Kai’s mum brought her to the site for the first time. “She wanted to come down, but she is quite ill and needs help walking. She was anxious so I was like I’ll come too,” says Kai. “The next week she didn’t come; she got really ill. So I came down by myself, and again the week after that, and I just never really left.”

Both feel disillusioned with the preoccupations of many people their age. “When you are protesting something like this, a lot of conversation can seem quite pointless – talking about I’m a Celebrity, Love Island etc.” says Callum, whose mum, Katerina Lawrie, is also a resident of the Maple Farm Camp. “I got really passionate about it very quickly,” says Kai. “I had a big group of friends and none of them understood at all.”

–

Tiga

“Everyone is entitled to come and ask questions about us. They should find out about the history of the individuals who are here, instead of just tarnishing us with the same preconceptions all the time”

Tiga is not his real name. “My Dad gave me this hat,” he remarks, pointing to a baseball cap on which his real surname is written. Originally from Leicester, Tiga has lived between both camps for the past year. “My home is miles away from Blackpool,” he says, “but, when the UK Government said frack the desolate North, I said no. It ain’t the desolate North. People live here; this is their livelihood.” Despite his dedication, Tiga’s family are indifferent. As if fate had willed it, later that day, we walk past his estranged brother in Blackpool – a policeman.

Tiga winces: he had his tooth pulled the day before. Life on the camps is not easy. “You have your ups and downs, especially during winter with the heavy weather, high winds and torrential downpours,” he says. “Cooking, cleaning, washing, tidying – we all just chip in and help each other out when we are struggling.” This sense of community extends throughout the anti-fracking movement; Tiga has campaigned at other camps located across the country: “Normally there are about 50 to 100 of us in one core group fighting the same industry.”

Tiga has been involved in environmental activism for seven years. “I gave up my life to become an activist; an activist for the people who cannot stand up and have their voices heard, whether it is because they are working or something else,” he explains. “If there is no one fighting on the front line they will get away with this. So I am fighting for the people who cannot get to the frontline.”

–

Jag (Just another guy)

“They could frack with unicorn piss and what came out would still be toxic”

“What got me involved in this was the fact that I realised it was a clear and present danger to my kids – I would sooner die than let anything happen to them,” explains Jag, an ex-soldier from Preston. A resident of New Hope, Jag has been involved in the fracking resistance for 18 months, since March 2017. “They are trying to bully us into submission. You can’t negotiate with bullies, you have to face them head on,” he says.

Jag was cycling around the country when he first became aware of the situation at Preston New Road. “This is Cuadrilla’s finest hour, this is as good as it is going to get for them, and they are a good ten months late and millions over budget,” he says. “It has taken them damn near two years to get this far because we have been delaying it.”

Jag is currently preparing to defend himself in court for three separate charges lifted against him for engaging in protest activities, including a lock-on that lasted 41 hours. “It seems strange to me that a corporation’s right to pollute trumps my right for them not to pollute. And that the planet they are choosing to pollute has no rights whatsoever,” he says. He has spent weeks compiling research for his defense from his cabin in a secluded corner of New Hope. For Jag, the court cases provide a further opportunity to raise awareness around the issues he locked-on to protest against: “I am defending myself because the law can’t do it, so I might as well call attention to that fact.”

–

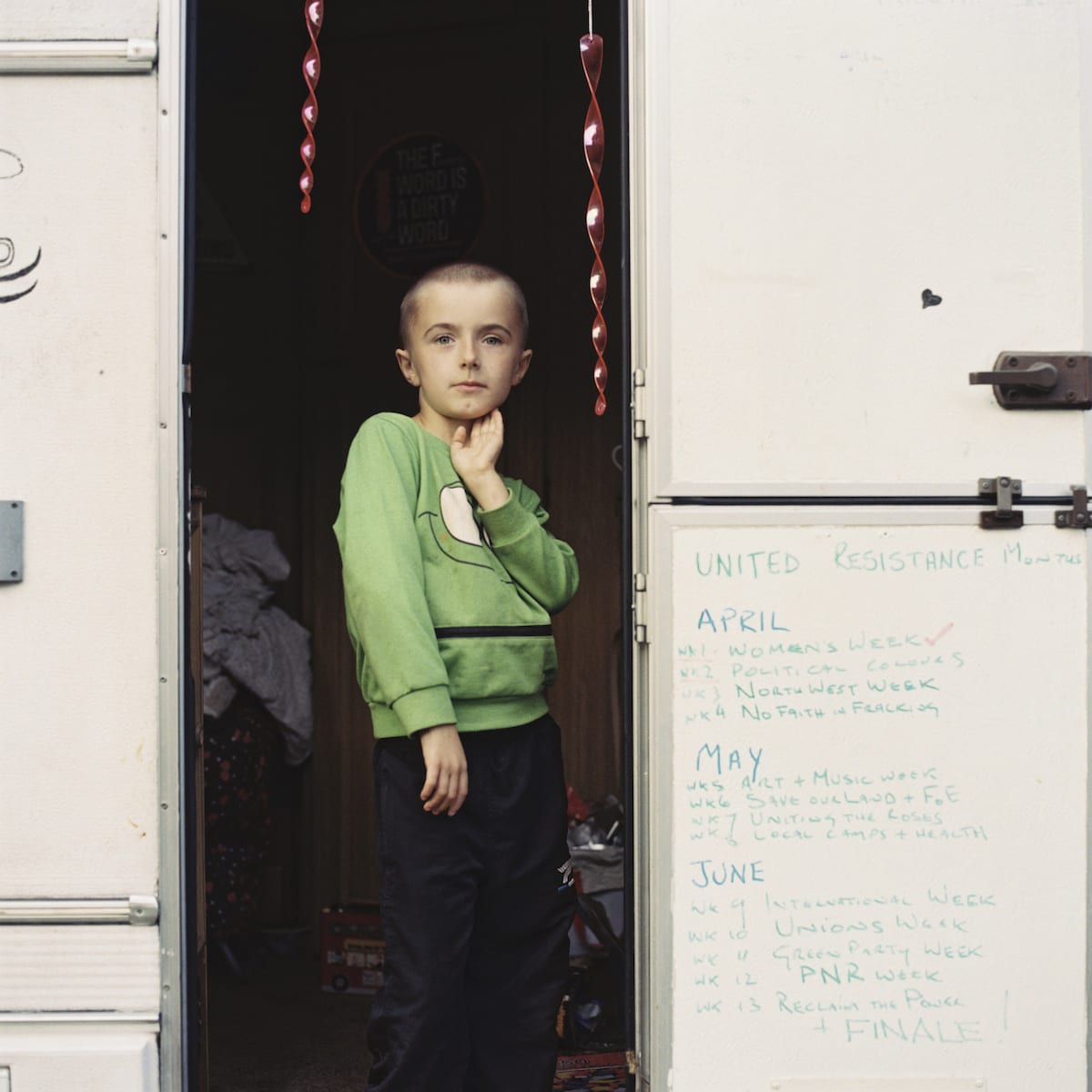

Deborah, Tom, Daniel and Matthew

“It is like an extended family. Everybody treats the children with respect. They are part of the community as they should be”

Deborah is a mother of three. She lives with two of her children in one of the small caravans in Maple Farm’s central courtyard. “I am originally from Longbridge, a nearby town, so I go back and forth, but I have basically been living here since July,” she says.

Deborah has never engaged in direct-action, choosing instead to support those involved in it. “I never thought I would get involved in something like this,” she says. “I was already disgruntled with the government. When they overruled the democratic decision of Lancashire County Council that was what tipped me and brought me here. I am staying until they have gone.”

Deborah studied Health and Social Care at Preston College, before beginning a part-time MSc in the subject at the University of Bolton. “I actually did my dissertation on the industrialisation of the countryside, so I fused my degree and the experience of being here,” she says. “It is difficult sometimes. I don’t have any Internet access so it can be a bit hard getting on with stuff. But, occasionally, I do nip home and have what I call an ‘office day’.”

Read the introduction to the project here; the second article, which considers the perspectives of local people both for and against the practice, here; and the third, which sheds light on the lives of anti-fracking campaigners, here.

–

Fractured Stories is a British Journal of Photography commission made possible with the generous support of Ecotricity. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.