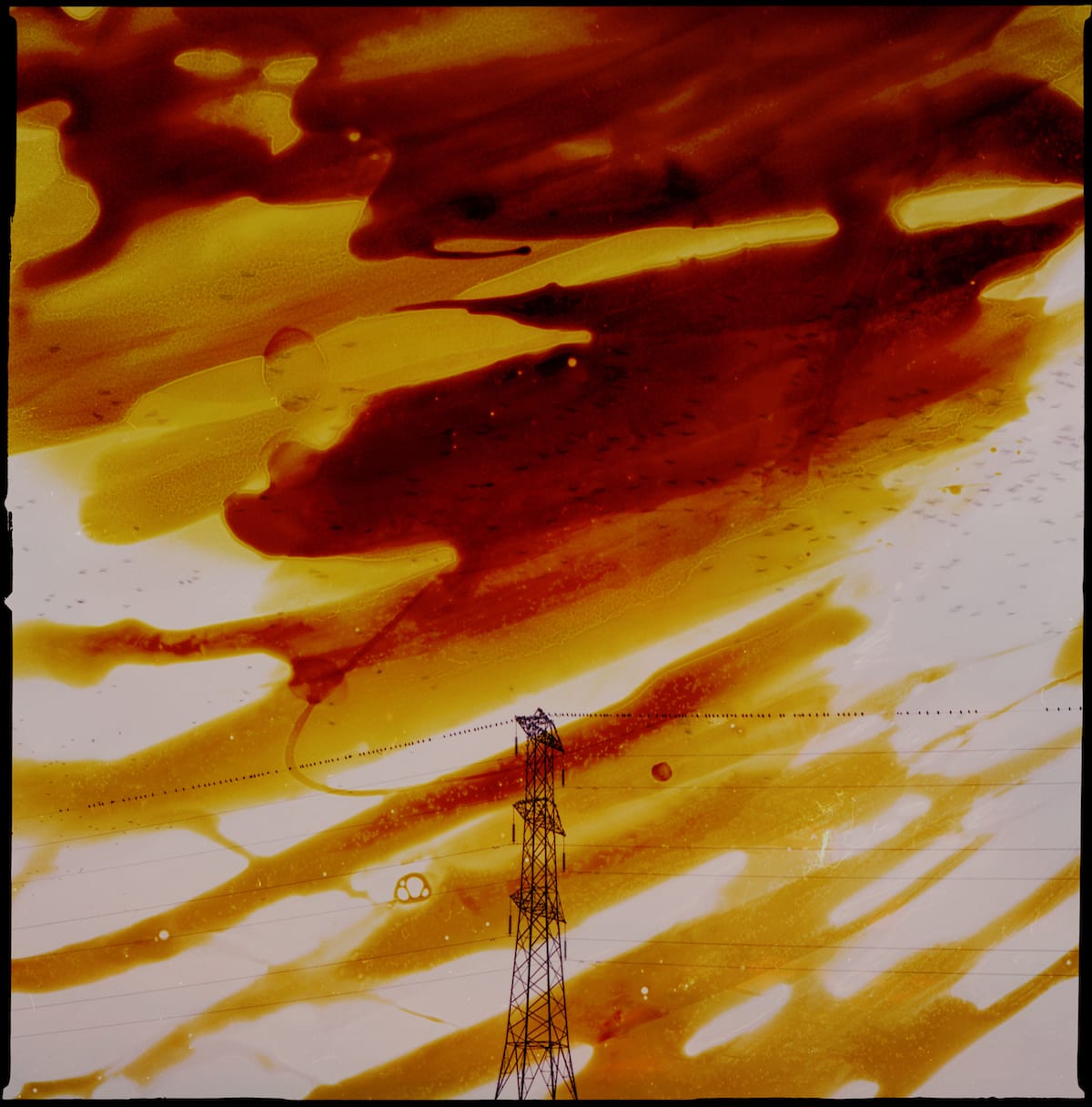

For Fractured Stories, a British Journal of Photography commission supported by Ecotricity, Rhiannon Adam spent four months immersed in the fracking debate. A series of editorials published on BJP-online tell the stories of the individuals she encountered. A number of images are corrupted with a constituent chemical of frack-fluid, alluding to the potential environmental impacts of the practice. The second in the series tells the stories of local people both for and against the practice.

In a living room on Blackpool’s South Shore, Claire Smith cradles a large rabbit. “He is the light of our lives,” says Smith. The rabbit’s enclosure extends across half of the room. “We found a Russian Dwarf hamster eight months before we found him, and then a guinea pig. They all belonged to the same woman but she has refused to accept ownership: she had five small furry creatures, of which we now have three.”

Smith is pro-fracking. As the rabbit – Ralphie – lollops about the room, she explains why. When the conversation ends, Rhiannon Adam photographs them both, Smith and Ralphie, against the prim furnishings of her award-winning hotel. “She is not the kind of person you would expect to support fracking,” says Adam. “The experience of photographing her in that space was quite surreal. But, ultimately, whether you are anti, or pro it, everyone has a different story. It is not as sensationalised as it has been presented in the media.”

For the last four months, Adam has immersed herself in the fracking debate. She spent much of her time at, and around, Preston New Road in Lancashire, home to the UK’s first active fracking site since a moratorium on the practice was lifted in late 2012. The first frack took place on 15 October 2018, midway through Adam’s project. The process has caused numerous tremors to date. A number of which have stalled operations in line with government regulation.

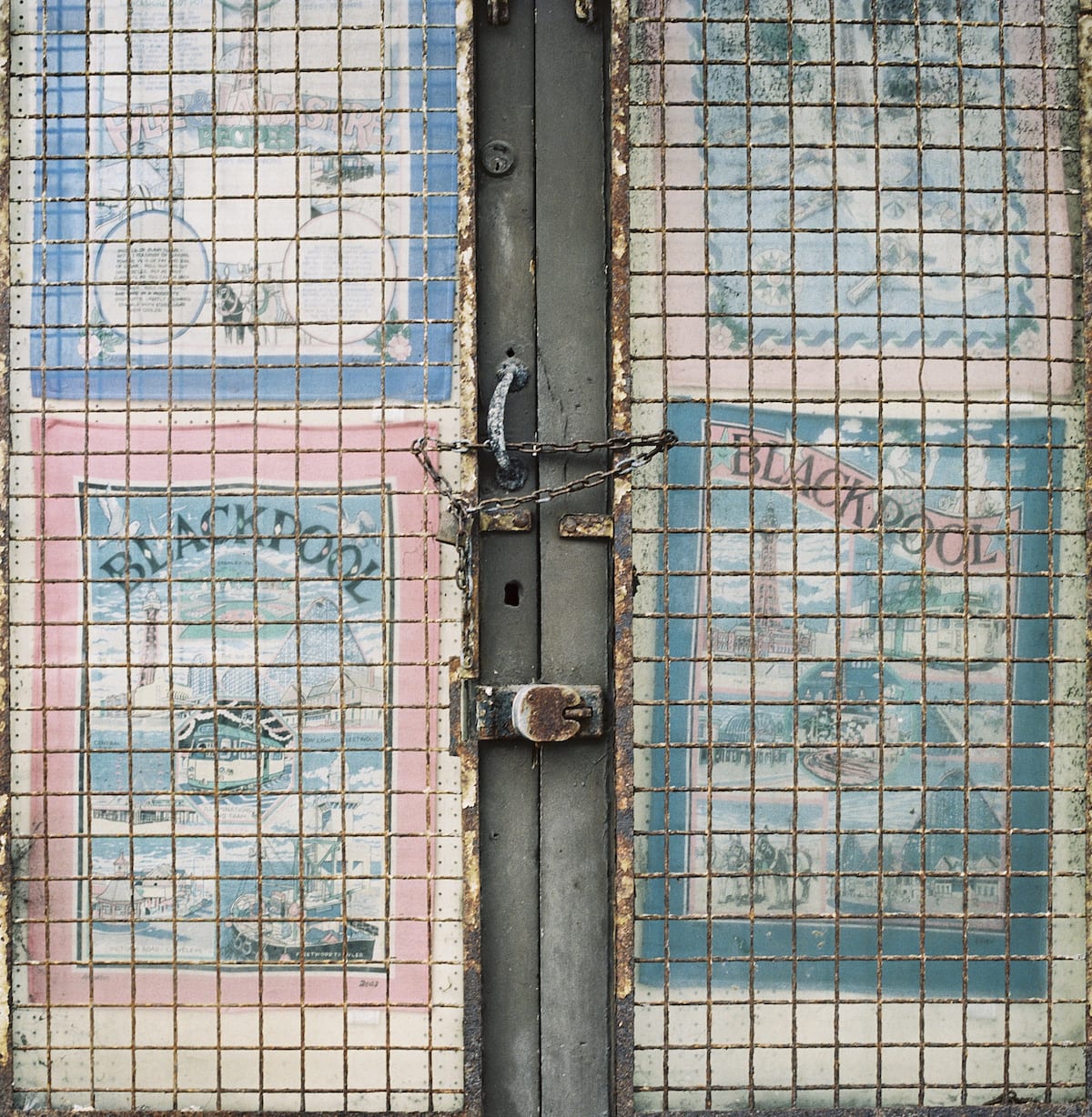

Preston New Road lies midway between Blackpool and Preston. From the late 1950s to the early 1980s, Blackpool was one of the go-to destinations for British holidaymakers from the UK’s industrial heartland. But, as the cotton and coal mining industries diminished, so did Blackpool’s once-burgeoning tourism trade. Cheap package holidays to warmer, more exotic, destinations contributed to the plummeting visitor numbers. Although tourism has somewhat recovered the city is still struggling. From July 2017 to June 2018 the unemployment rate stood at 5.5 percent; one percent higher than the national average. In 2017, the End Child Poverty initiative reported that child poverty in the area was at 36.52 percent.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, as it is more commonly known, is a controversial process used to extract oil and gas trapped in shale, and other, rock formations. It involves drilling down deep into the earth; a mixture of water, sand and chemicals is then injected at high pressure to fracture the rock. The gas released travels into the water stream and either flows back, or is pumped, to the surface.

Fracking is more common in the US where it has revolutionised the energy landscape: over 100,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled and fracked in the country since 2005. Despite Europe being projected as the new fracking mecca, it has been largely unsuccessful. The process is not permitted in France, Germany or Bulgaria; Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have all placed their own suspensions on it.

In the UK, fracking first came to national attention in the spring of 2011 when Cuadrilla fracked at a site in Preese Hall in Weeton, Lancashire, causing earthquakes; a moratorium was subsequently imposed until late 2012. Public opposition resurfaced in 2013 as protests sprang up around a proposed site near the West Sussex village of Balcombe and the drilling of a well at Barton Moss, Salford. Preston New Road became the focal point of the fracking debate after Cuadrilla applied to drill there in 2014.

Opponents stress the potential environmental impacts: earthquakes, pollution of water supplies, water wastage and air pollution. Other concerns include, noise pollution, the industrialisation of the countryside and a detrimental effect on house prices. Ultimately, it represents a continued investment in fossil fuels at a time when eliminating our reliance on them is crucial.

Advocates for the practice point to its potential for job creation, along with its ability to offer us energy security and act as a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future.

Those in support of fracking, like Smith, extol the practice’s potential for the creation of local jobs. In January 2018, Cuadrilla stated that its operations in the area had created just 50 jobs locally. Following the announcement of its second exploration well, the company gave £100,000 to residents in the surrounding areas. It was decided that this should be split proportionally between households located within 1.5 kilometers from the site. Properties within one kilometer were entitled to £2,000; those located between one and 1.5 kilometers were entitled to £150. “How many businesses have spent 10 million pounds in Lancashire over almost two years,” says Preston-based John Kersey, managing director of a hair salon, another supporter of the practice who Adam met.

In the area directly surrounding the site Cuadrilla’s ‘investments’ have divided the community. Many declined the money or donated it to the protestors campaigning at the Preston New Road site. Others accepted. “Cuadrilla have tried to win over the landowners and a lot of them have been duped by them,” says John Tootill, who owns a nursery next to the site and has vehemently opposed Cuadrilla‘s activities since they began. “ They have taken money from them for access onto the land, I would have been one of them but I did not want anything to do with Cuadrilla because that would be so hypocritical,” he says.

“The subject of fracking is not just a political issue, which is how the press generally report it,” says Adam. “It is also about the individuals and, the fact is if you believe that strongly in something it takes a lot of gumption to stand up and fight it. To be willing to alienate yourself from your community; to take a risk because of your own beliefs and convictions – that is quite powerful.”

Below, her images tell the stories of the locals she encountered both for and against the practice:

–

Gina Dowding

“It is as if we have been left with no choice because the democratic process is not working”

Gina Dowding has lived in Lancaster for more than 30 years and is a Green Party Lancashire County Councillor for Lancaster Central. She got involved in politics out of concern for the environment before fracking was even on the agenda. In November 2017, Dowding engaged in a direct action that saw her convicted at Blackpool Magistrates’ Court. She was one of 12 people, including two other councillors, who engaged in a lock-on to barrels and pipes outside of the Preston New Road site.

“In the past, I never felt that comfortable about taking direct action,” she says, “that is one of the reasons that I got involved in local council politics; I felt that it was important to be part of the system in order to try and change it.” Dowding lost faith in this approach when the Lancashire County Council rejected Cuadrilla’s bid to drill at Preston New Road in 2014, but Sajid Javid, then secretary of state for the Department of Communities and Local Government, overruled the decision.

Dowding regards the development of the shale gas industry as undermining any action the UK is trying to take nationally against climate breakdown. Many advocates assert that fracking offers a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future and is crucial for energy security. “But, this misses the obvious,” says Dowding, “a new fossil fuel just locks us into carbon production for at least another decade or two. It also delays the expansion and development of our renewable energy industries; green energy provides permanent energy security and is essential to avoiding climate catastrophe.”

–

John Kersey

“I have always been a hairdresser. I love the profession. What you are probably thinking is why the connection between fracking and hairdressing?”

John Kersey has run a hair salon in Grimsargh, a village in the city of Preston, for 22 years. He fell into the profession aged 14 and has been in the industry for over 50 years. “Having been trained properly myself, I wanted to do the same for others,” he says, “I have trained 150 hairdressers to date.” Kersey is a former chairman of the Lancashire branch of the Institute of Directors, an organisation for company directors, and business leaders, he is also a member of the North West Energy Task Force. It was on joining the IoD that he became interested in fracking.

“I felt that fracking was a major opportunity for Lancashire to come back to its heritage and be a great industrial county once again,” he says. Kersey believes that the industry will provide a source of jobs and energy security. He was involved in a report that the IoD published on the subject in 2012, sponsored by Cuadrilla, which concluded that shale gas has the potential to create jobs, generate tax revenues, reduce imports and act as a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future. In late 2013, he stood as a witness in Parliament, as part of an inquiry by the House of Lords’ Economic Affairs Committee into the possible economic impact of shale gas and oil on the UK. The evidence he gave stressed the importance of fracking for energy security.

“There is not another option,” he continues. “We are where we are. We have energy security to think about, we have houses to heat, we have children to educate.” Kersey recognises that renewables are the way forward, but regards fracking as central to this transitional phase. “I would like us to be 100 percent renewable now,” he says. “But you cannot go from being where we are today to that tomorrow; there has to be this transition phase … if we continue to use fossil fuels, which we are inevitably going to do for the short term, we need to look into solving the problems associated with those and creating alternative ways of doing things.”

–

John Tootill

“This industry is in its death throes — very soon it will cease. It cannot carry on as it has no future whatsoever”

John Tootill has run Maple Farm Nursery, located just 800 metres from Preston New Road, for 34 years. He lives there with his family. “I started the business with my dad. We worked together as a team for many years until his death a couple of years ago,” he says. “My dad was extremely concerned by Cuadrilla’s proposals to carry out fracking so close to our nursery and feared the worst for his family home and business.” Tootill had no idea about fracking when Cuadrilla Resources first applied to drill near his home. After discovering what the process was, and the risks it posed, he was horrified: “I am just trying to defend my family, my community and all the things that I have been brought up to believe in.”

One of Tootill’s concerns is the effect that the practice could have on his livelihood. “I want people to be able to visit the nursery without fearing for their health and their children’s health.” He donated a portion of his land to the protectors, on which they have set up Maple Farm Camp. “It is a big sacrifice because it is a site on the main road, which, from a business point of view, is an important location,” he says. “I am happy that it is being used to further the campaign against this harmful process.” The camp also provides a “safe haven” for protectors: “Maple Farm offers a refuge for people to feel secure because the policing can be very oppressive.”

Tootill himself has had a number of run-ins with the police. On the gates of Maple Farm Camp, a collection of large signs denounce fracking and the myriad dangers associated with it. In 2016, Fylde Borough Council sought to prosecute Tootill for unauthorised advertising. The case was dropped by the Council once his barrister disclosed to the court that the decision to prosecute him was made by Fylde borough councillors who had received money from Cuadrilla. He has been arrested twice: once for obstructing the road, and again for obstructing a police officer during an anti-fracking protest. The charges were dropped for both cases. “One of the reasons I was targeted by the police is because I am a local businessman,” he says. “I am seen as the face of respectability; that is not the face that industry and the government want showing opposition to them. And I have made my opposition very, very clear.”

Cuadrilla’s activities at Preston New Road have polarised the local community. “Cuadrilla has worked on this community for years: they have splashed money around, to all sorts of organisations: sports programmes, football and rugby clubs, schools, village halls, the list goes on,” says Tootill. “Many local people are frightened to show opposition to what is being imposed on them.” But, Tootill has remained dedicated to the fight. “The sooner that this dirty, reckless industry packs up and goes, the sooner I can get on with normal life,” he says. “Stopping it here will empower people to stand up for their communities in other places where the industry is trying to get a hold.”

–

Claire Smith

“There is nothing else on the agenda that will improve our situation; fracking has the potential to do just that”

Claire Smith and her husband Mark have lived in Blackpool their whole lives, along with their children and extended families. “When I first heard about fracking I thought this is serious,” she says. “Is this something that is going to have a hugely detrimental effect on our health, on our environment? I have to admit I was confused.” Today, she is a vocal supporter of fracking and part of North West Energy Task Force, funded by Cuadrilla Resources and Centrica, which encourages local businesses to become part of the shale gas industry’s supply chain.

Smith is the President of Stay Blackpool and has been a hotelier for 24 years: she runs two award-winning hotels. “Tourism is what we do. And we do it very, very well,” she says. However, tourism in Blackpool is not what it once was: the industry has declined with significant social and economic impacts. Smith is enthusiastic about fracking’s potential for job creation. “I want a better Blackpool; it is that simple,” she says. “I want more jobs. I want fewer derelict buildings, better healthcare, more teachers in schools, more police doing what they should be doing. The only way that we are going to achieve that is having more people in work.”

“I am not completely right, but the anti-frackers aren’t either,” she says. Smith has little sympathy for the protest tactics of some anti-fracking activists. “A lot of them are not from here; they have no idea about the problems that we face.” She does, however, empathise with the locals whose livelihoods could be compromised: “They are the ones that I do think have genuine reasons for being against it. I absolutely do feel for them … any change is scary.”

Read an introduction to the project here; the first article, which offers a glimpse into life on the frontline of the fracking resistance, here; and the third, which sheds light on the lives of anti-fracking campaigners, here.

–

Fractured Stories is a British Journal of Photography commission made possible with the generous support of Ecotricity. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.