For Fractured Stories, a British Journal of Photography commission supported by Ecotricity, Rhiannon Adam spent four months immersed in the fracking debate. A series of editorials published on BJP-online tell the stories of the individuals she encountered. A number of images are corrupted with a constituent chemical of frack-fluid, alluding to the potential environmental impacts of the practice.

It is Monday 15 October 2018. Today, Cuadrilla Resources will frack for the first time in the UK since 2011. The stretch of road outside the Preston New Road site in Lancashire is deserted; a misty haze hangs over the scene. Further up, a white van, mounted with scaffolding, blocks the entrance. One protester has d-locked his neck to the structure; another has attached her arm. Campaigners from around the country congregate with signs and placards, the police stand on patrol.

The press is here, in the midst of the action, but Rhiannon Adam holds back. This is exactly the type of image she wants to avoid: a snapshot of an anonymous crowd demonstrating against a process, which is, largely, invisible. “The subject is difficult to photograph,” she says, “the only way I believed that the story could be told is through the people.” For Adam, listening to an individual’s story dictates how she photographs them. Her ultimate aim: to redirect the narrative away from the singular news piece and give an identity to those involved.

For Fractured Stories, Adam began by living and working among the protesters, or protectors as they prefer to be known, demonstrating at the Preston New Road site. From seasoned activists to incensed locals, the individuals she encountered were drawn from a wide demographic. “Everyone is entitled to come and ask questions about us,” remarked Tiga, a former resident of Maple Farm Camp, now of New Hope Resistance Camp; the two permanent protection camps located just feet from the site’s main gate. “They should find out about the history of the individuals who are here, instead of just tarnishing us with the same preconceptions all the time.”

Located midway between Preston and Blackpool, Preston New Road became the focal point of the fracking debate after Cuadrilla applied to drill at the site in 2014. The Lancashire County Council rejected the bid. However, two years later, Sajid Javid, then secretary of state for the Department for Communities and Local Government, overruled the decision. Cuadrilla was granted planning consent and completed the UK’s first two horizontal shale gas wells in 2018.

In July of this year, the UK Government caused controversy when it gave the final go-ahead for fracking to begin at Preston New Road on the last day of Parliament before the summer recess. The first frack went ahead on 15 October 2018; midway through Adam’s project. The process has caused numerous tremors to date, a number of which have stalled operations in line with government regulation. A minor earthquake that occurred on Tuesday 11 December 2018, when Cuadrilla resumed fracking after a one month break, was far higher than the government’s regulatory threshold and on par with the tremor that led to a moratorium on the practice in 2011.

Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking’ as it is more commonly known, involves pumping a mixture of water, sand and chemicals at high-pressure deep underground to break apart rock, and extract natural gas and oil. Some support the practice, viewing it as an opportunity for job creation, energy security, and even a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future. Others are deeply concerned. At Preston New Road, local people, many of whom feel their democratic rights have been infringed, joined forces with climate campaigners to protest against the process on environmental, social and political grounds. Opponents stress the potential environmental and health impacts: earthquakes; water wastage; air and water pollution leading to cancers, birth defects and damaged reproductive health. Other concerns include its detrimental effect on house prices, noise pollution and the industrialisation of the countryside. Ultimately, it represents a continued investment in fossil fuels at a time when eliminating our reliance on them is crucial.

Adam captured individuals on both sides of the debate. “It has been reduced to these two polarised sides of one story,” she says. “This narrative has deleted the personality of the individual: there are different reasons why people get involved; there are so many individual motivations.” She visited John Tootill, the owner of Maple Farm Nursery, which sits on a plot of land just 800 metres from Preston New Road. Tootill has run the nursery for 34 years. He has demonstrated against the fracking site since its announcement, allowing the use of a portion of his land, one of his polytunnels and his running water to Maple Farm Camp. “Most of the people in opposition to the practice are ordinary members of the community,” he says. “The media presents this extreme image of what is happening; the more extreme something is the more newsworthy they believe it to be.”

Adam also met with local business owners in nearby Blackpool and Preston, who support the practice. John Kersey, a hairdresser of more than 50 years, is a vocal advocate. From a styling chair in his immaculate salon, Kersey explains the importance of fracking for local employment and energy security. “There isn’t another option. We are where we are: we have energy security to think about, we have houses to heat, we have children to educate and these are the things that make that happen,” he says.

Fracking moves in and out of the spotlight. The media tends to cover a significant moment or event, but, the everyday realities remain unknown. Working at and around the site for four months to date, Adam is determined to create something different. “Being there for so long I have come to appreciate the little things that people do,” she says. “Like locals who have opened up their houses to allow protesters to shower; or the people who do bits of laundry and drop them off at Maple Farm Camp; or someone who has never been vegan in their life but is now making vegan food to bring to the main gate.”

The ebb and flow of the project has evolved with the seasons: “The people I have encountered have changed,” she says. “Many have had to return to work at the end of the summer.” And yet, each of Adam’s images exist as a standalone still that depicts the subject in that moment. She achieves this, in part, by removing them from the setting in which they might otherwise be shown. “I wanted my images to say: This is not just a person who is protesting, this is a person with a life, and interests, and family,” she explains. “I sometimes feel that taking a photograph is a bit like stealing someone’s soul and you have to be responsible with the soul that someone gives you.”

Fracking is more common in the US where it has revolutionised the energy landscape: over 100,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled and fracked in the country since 2005. Despite Europe being projected as the new ‘fracking mecca’, it has been largely unsuccessful: the process is not permitted in France, Germany or Bulgaria; Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have all placed their own suspensions on it. In the UK, estimates suggest that the amount of shale gas lies between 2.8 and 39.9 trillion cubic metres. According to former Prime Minister David Cameron, if only 10 percent of those reserves were extracted, this would provide the equivalent of the country’s total gas needs for 51 years.

In the UK, Preston New Road exists at the epicenter of the fracking resistance, but the process has provoked nationwide debate for almost a decade. The issue initially entered into public consciousness when Cuadrilla hydraulically fractured the UK’s first shale gas exploration well at Preese Hall in 2011. Two earthquakes were detected and a moratorium on the process enforced. This was only lifted in late 2012 after the introduction of a new regulatory regime geared toward monitoring and reducing seismic risk.

As proposed sites began to emerge, public opposition gained momentum. Protests sprang up around a proposed site near the West Sussex village of Balcombe and the drilling of a well at Barton Moss, Salford – the same site, located just seven miles from her home, which provoked Power’s involvement in the anti-fracking resistance. In May of this year, the UK Government introduced a number of measures to help facilitate the practice, including a £1.6m fund for planning authorities to speed up fracking applications. Third Energy and Ineos, a large petrochemicals group headed up by the multi-billionaire Jim Ratcliffe, are also looking to frack at sites across the country. Today, campaigners travel miles to Preston New Road to show their resistance. Adam met with these individuals to gain an insight into their lives outside of the protest-context.

In Sheffield, she visited Simon Roscoe Blevins: one of three activists who were imprisoned for engaging in a lock-on at Preston New Road that lasted almost 100 hours in July 2017. Blevins, Richard Roberts and Richard Loizou were each sentenced to between 15 and 16 months in September of this year. They were later released after six weeks when the court of appeal ruled that their sentences were excessive. “Through your research, you are aware of what is it at stake. And you feel the need to start putting yourself on the line for it,” explains Blevins, a soil scientist. “Ultimately, when you look at it, people on either side of the debate generally want the same thing, it is just different ideas that will help us achieve those aims.”

In London, Adam photographed fashion designer and activist Vivienne Westwood, a long-standing and vocal opponent of the practice.“I am involved because I am an activist. The people in power who want fracking, they are in the business of wrecking the Earth and selling it for tuppence,” she says. “So far, it has been a disaster: they have all lost their money.” Adam also shot John Sauven, executive director of Greenpeace. “The fracking protesters are real heroes: they are people who have protested day and night for many years,” says Sauven. “They have sacrificed a huge amount. And, in the case of the three sent to prison, sacrificed their liberty for something that they believe in.”

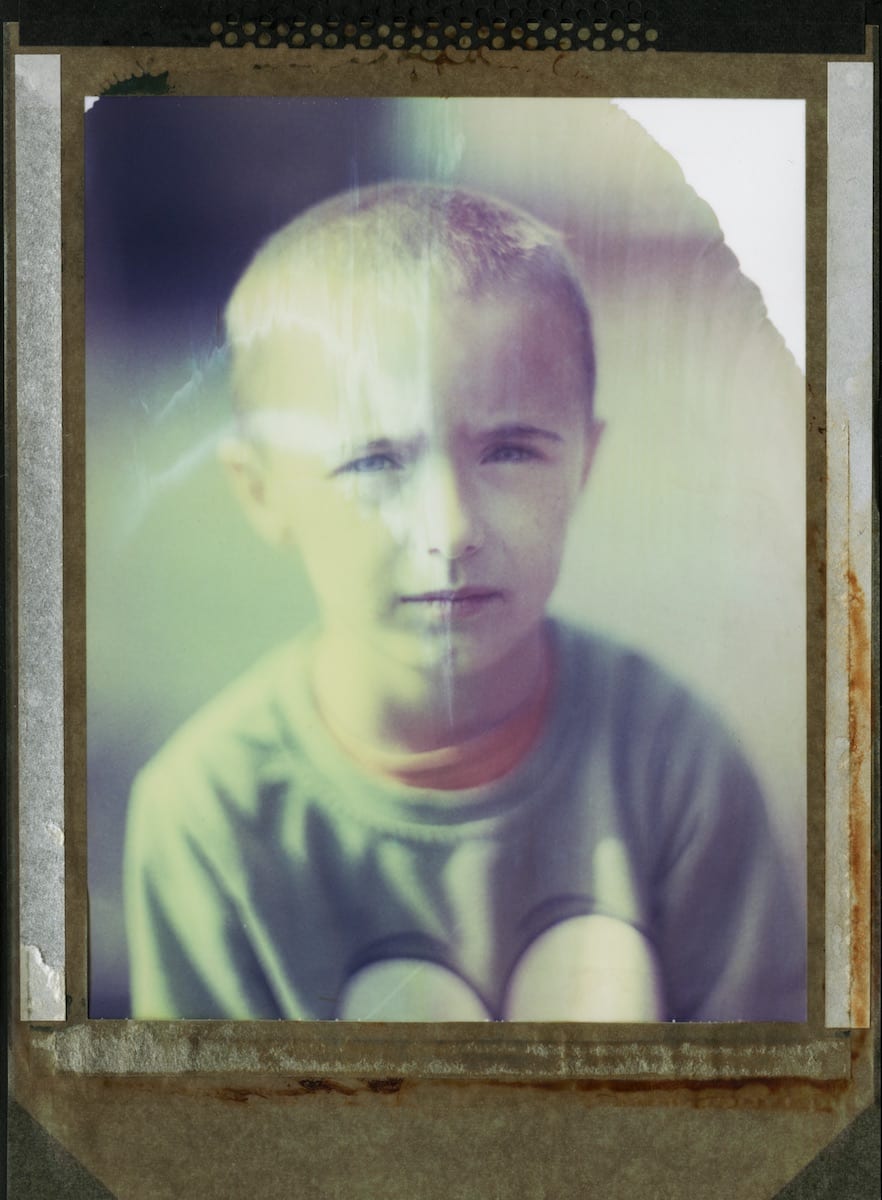

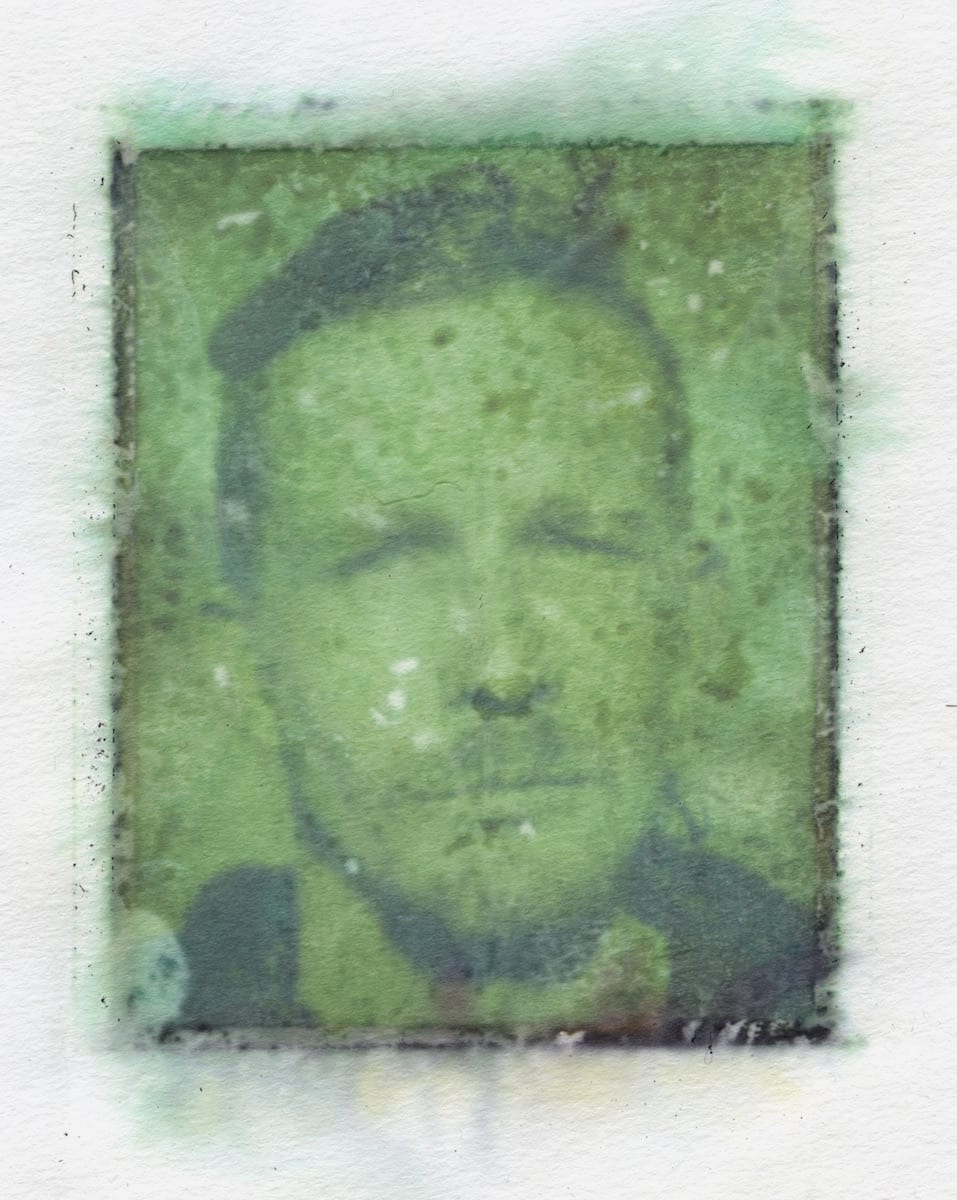

Adam specialises in shooting with instant cameras; a number of her Polaroids are featured in this project. With instant film, each photograph she takes physically embodies the moment at which it is made. “If I am shooting a picture of you here and now, in this temperature and in this light, and I haven’t fiddled with anything, there is a kind of purity in it,” she explains. “You can see my intention.” And so each still is also emblematic of a shared experience: a moment between “me the photographer and you the subject, which is like a creative bond.”

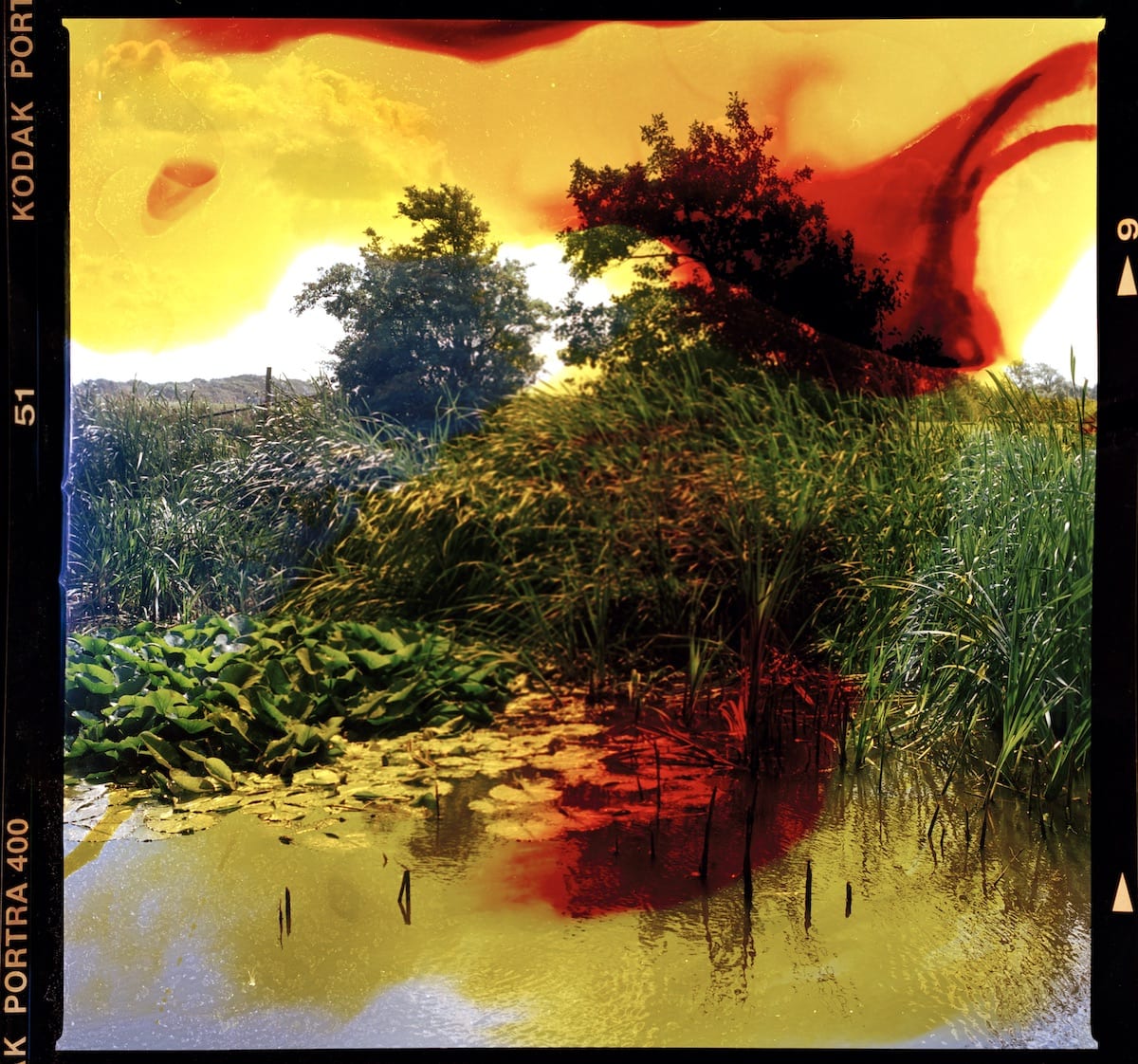

It was harder for Adam to make visual the as-yet invisible environmental issues that many fear fracking will inflict. She depicted these by processing select images with a constituent chemical of fracking fluid. In the UK, operators must declare what chemicals they use. Cuadrilla fractures shale rock by pumping a mixture of water, sand, and a chemical called polyacrylamide through a horizontal well. Although the Environment Agency has assessed polyacrylamide as being non-hazardous to groundwater, it is a controversial ingredient given its ability to degrade and secrete acrylamide: a known toxin and carcinogen.

Adam also used water from Carr Bridge Brook, the nearest watercourse to the site. In 2017 the Environment Agency recorded two separate incidents of water, which contained silt, leaking into the brook from Preston New Road. Both instances breached Cuadrilla’s permit conditions and a discolouration of the water was observed. Many fear that contaminated water could runoff from the site and pollute the surrounding area.

“Film chemistry relies on clean water to be able to be processed properly,” says Adam. By employing a disrupted aesthetic, she alludes to the potential threats of the practice on the landscapes and lives of those pictured. “I like the idea of creating something beautiful from something damaging,” she says, “in some ways, this duplicity creates more discussion, and will hopefully raise awareness of the process involved in fracking by engaging those who have not necessarily been following the developments thus far.”

Entitled The Rift: Chapter 1, PNR, Adam intends to continue the project beyond the commission period. “It is interesting because it is almost like the gradual spread of a disease,” she says. “Like watching something in slow motion.” The well at Preston New Road is only the start. It is not a commercial site: the gas will be flared not captured. An estimated 20 to 40 wells will be needed to ascertain the commercial viability of the process. But, if the industry does take off, the UK’s countryside will be covered. There are already plans for further exploration at nearby Roseacre Wood, across North West England, Yorkshire and the East Midlands. This summer, the UK Government set up a consultation on whether shale gas development should become ‘permitted development’: a category usually reserved for activities like putting up a garden shed. This would enable fracking companies to drill at will without applying for planning permission.

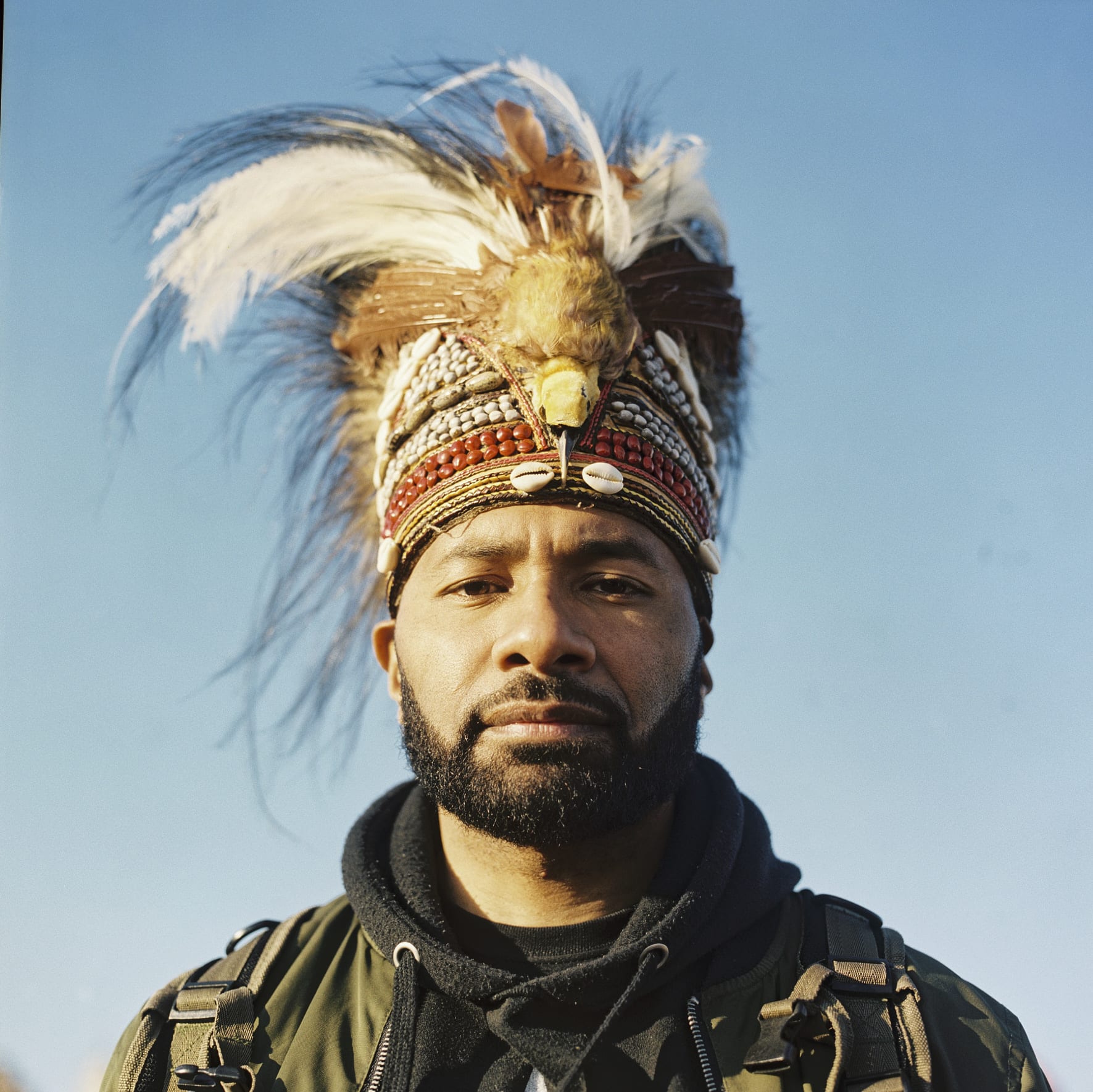

The debate around fracking at Preston New Road also speaks to the issue of climate change more broadly. On 17 November 2018, Adam travelled down to London from Preston New Road with campaigners to attend a mass demonstration organised by Extinction Rebellion. Thousands of protesters occupied five bridges in central London to draw attention to climate breakdown and force governments worldwide into action. “I lost my own father due to the colonialism remaining in my home: West Papua,” said Raki Ap, a climate change witness from the Free West Papua campaign. “It is the home of fossil fuel industries, such as BP, which continue to destroy my homeland. The urgency with which we must fight climate change is felt by West Papuans every day.”

“If you are from elsewhere in the UK, what is happening at Preston New Road may seem insignificant,” says Adam, “but it is an indication of our continued reliance on fossil fuels on a global scale and the myriad environmental issues these cause.” Midway through the commission, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report pointing to the importance of limiting global warming to a maximum of 1.5C, stating that we have only a dozen years left to do so. Carbon pollution would have to come down to zero by 2050 for us to achieve this. In the seven years that Cuadrilla first fracked at Preese Hall, renewable energy has gone from providing a 10th of our electricity to supplying a third of it. As Adam so aptly put it: “Why are we investing in the fossil fuel industry when we should be moving away?”

Ultimately, her work takes us inside the fracking debate: shedding light on the human stories playing out around this controversial process. Although the issue is ongoing, the series documents a specific chapter in a narrative that is deeply complex.

A series of editorials published on BJP-online tell the stories of the individuals she photographed. Read the first, which offers a glimpse into life on the frontline of the fracking resistance, here; the second, which tells the stories of local people both for and against the practice, here; and the third, which sheds light on the lives of anti-fracking campaigners, here.

–

Fractured Stories is a British Journal of Photography commission made possible with the generous support of Ecotricity. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.