“People always ask me why I stopped photographing people,” says Anthony Hernandez, who in the mid-1980s, moved away from the black-and-white street photographs that had made his name. He was 17 years into his career and an artist in residence at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, when he made the shift; initially thinking to photograph the infamous strip, he ended up travelling into the desert and making pictures of the left-over target shooter debris for what was to become a pivotal project, Shooting Sites.

What Hernandez didn’t realise till many years later was that this shift was unconsciously connected to what he calls his first ever “photographic gesture” at 17 years old. It was an image, which is now sadly lost, of an empty lot strewn with rusting car parts and overgrown weeds. “You might say that the 35mm street photographs were the start of my career. Yes, I did do those, but the real beginning was that empty lot,” he says. “Why I was attracted to that, I don’t know.”

Hernandez was born in Los Angeles in 1947, and grew up near Aliso Village – an East LA public housing project that he later returned to photograph, and which was demolished in 2000. He now lives Idaho, but has produced the majority of his life’s work in LA.

Aside from a few basic darkroom courses at East Los Angeles College, Hernandez is self-taught. After graduating high-school he hitchhiked across the continent to New York, seduced by the gritty energy of a creative city, and eager to immerse himself in the world of jazz music and art. But when he called his mother in LA to let her no he was okay, his career as an artist was put on hold – the draft papers had arrived.

From 1967-1969 Hernandez served the United States Army in Vietnam, and was randomly selected to work as a field medic 1968. He has connected this experience to later projects such as Landscapes for the Homeless and Shooting Sites, telling Erin O’Toole, curator of the retrospective now going on show in Madrid, that photography helped him to construct a new life when he got home, offering “a way of being in the world that was meaningful and generative”.

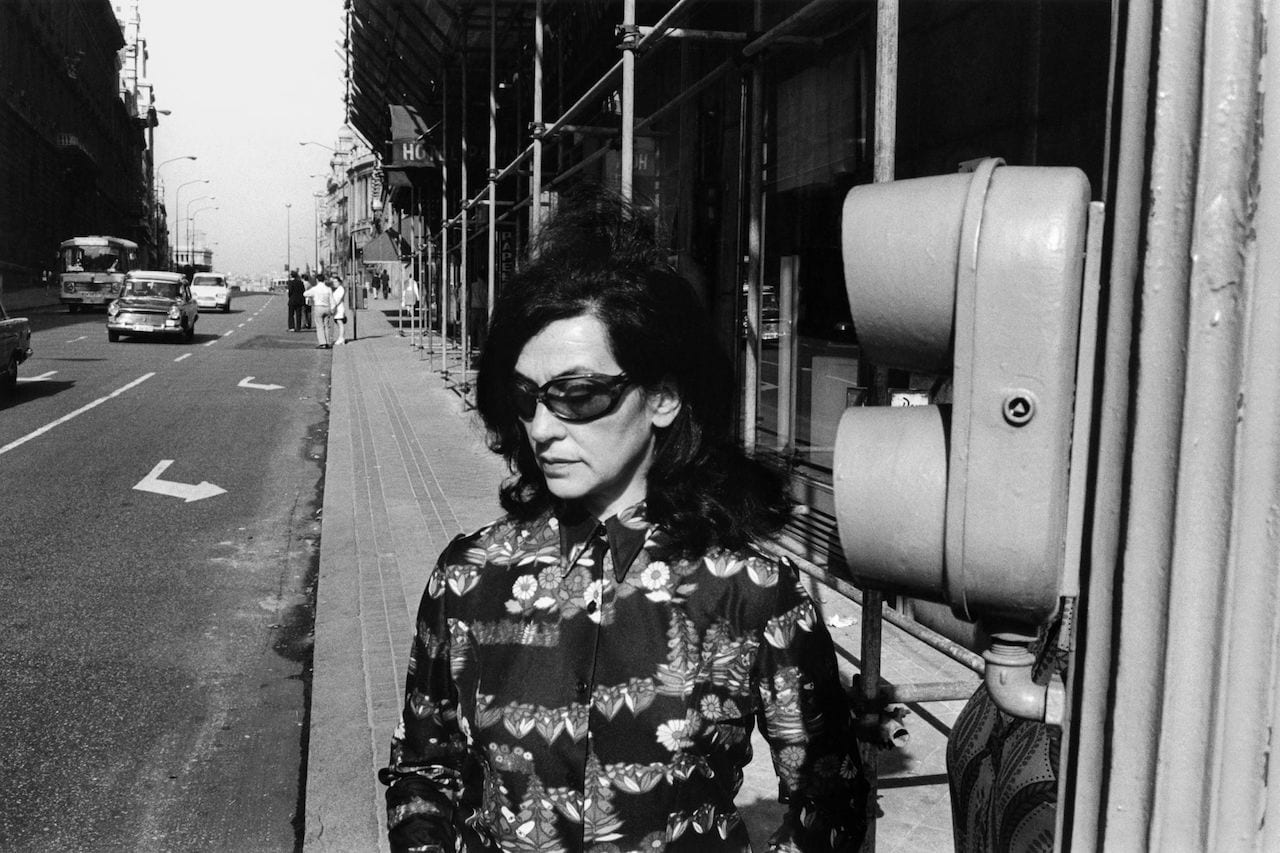

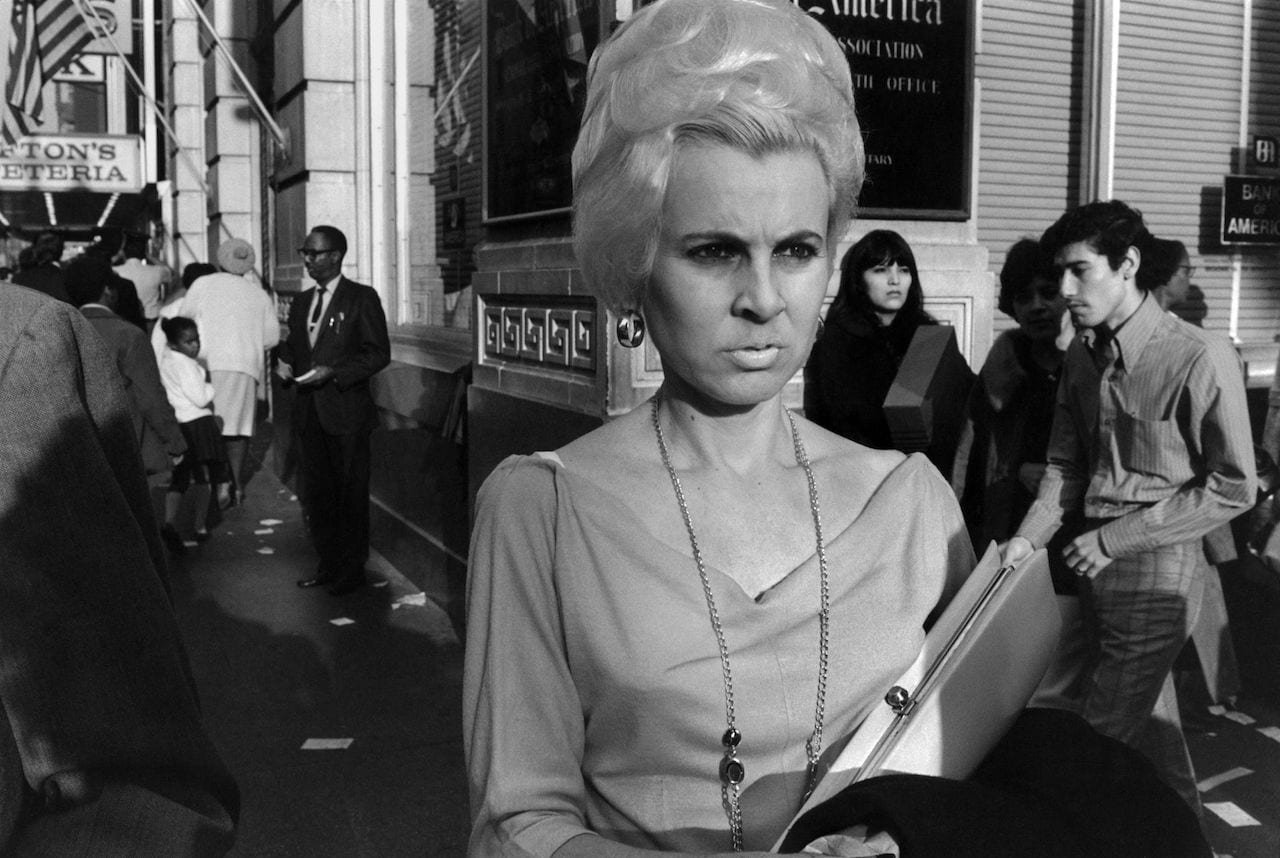

Within half a year of returning from Vietnam, in the summer of 1969, Hernandez enrolled in a weeklong workshop led by Lee Friedlander at the Center for the Eye in Aspen, Colorado. He cites Friedlander as one of his earliest influences – though his first real influence was Edward Weston – and, after taking this course, Hernandez began to make 35mm black-and-white street photographs in LA, moving around the city in a routine he refers to as “a dance in the street”.

Hernandez would venture out with his Leica on a pre-set focus, so that – as long as he judged the distance right – he could capture a shot and quickly move on, often before his subjects had realised what had happened. He reminisces fondly on days spent dancing around LA, twirling down each avenue through the constant rush of people and vehicles. “It was a very fluid way of working that I really enjoyed,” he says.

Hernandez thinks of these early street photographs as his “childhood experience”. “It really didn’t have to do with the history of street photography, it had to do with my own experience of growing up in downtown LA,” he reflects. “It made sense to start in the place I knew best.”

Over the 1970s and 80s, he continued to produce work all over the city, including a series on city bus stops, Public Transit Areas, and related bodies of work like Public Use Areas and Public Fishing Areas. “I always thought of LA as my big studio,” he says. “I haven’t exhausted the city, there are still things I want to photograph there. It’s a very rich place, and it’s part of who I am”.

In 1985 Hernandez made his first body of work in colour, capturing the negligent wealthy on the two-mile-long street in Beverly Hills. Unknown to him at the time, Rodeo Drive would be the last series he’d make as a street photographer.

“It wasn’t a conscious decision to stop photographing people, it just happened,” says Hernandez, describing his process – whatever the subject – as intuitive. “It all goes back to that first photographic gesture at the empty lot. I’m finally making a connection back to that”.

From 1986 onwards, Hernandez’s work has been consumed by themes relating to desertion and social landscapes. Landscapes for the Homeless, produced between 1988-1991, examined the makeshift shelters located under LA’s freeways, a project he sees as the most difficult of his career. “The hardest pictures I’ve ever made were the homeless pictures,” he said in conversation with Lewis Baltz, a close friend and contemporary, in 1995. “I wasn’t in a war zone but it was as if I were.”

In 1992 Hernandez and his wife, novelist Judith Freeman, moved to rural Idaho, where he still lives today. They regularly travel back to LA, but he feels this distance is good for his work. “If I leave the city for four or five months, it’s fresh again,” he explains. His three most recent projects, Everything (2002), Forever (2007-2012) and Discarded (2012-2015), are formal studies of landscape that approach themes and subjects that are both new and old. For the first he travelled down the river banks of Los Angeles River, then he returned to homeless encampments, shooting from the opposite perspective, and finally he examined desert communities east of LA, through landscape, still-life and rare portraiture.

This year Hernandez will be 72, but he shows no signs of slowing down. His most recent images are shot through a metal filter, purpose-made by a friend with equal sized holes punctured through it. It stands on a tripod in front of his camera to create abstract and minimal landscape photographs. The project is part of his Guggenheim fellowship, and some of it will be on show at the retrospective in Madrid for the first time.

“I always wanted to get away from any kind of distortion, I wanted it to be straight onto the scene and lined up,” he says. “After all these years, the straight photograph is still there, but I want to look at things in a different way. I think this a very rich way of working now, and it is totally my own. I’m very happy about that”.

https://anthonyhernandezphotography.com/ A retrospective of Anthony Hernandez’ work will be on show at the Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid from 29 January – 12 May 2019 https://www.fundacionmapfre.org/fundacion/en/