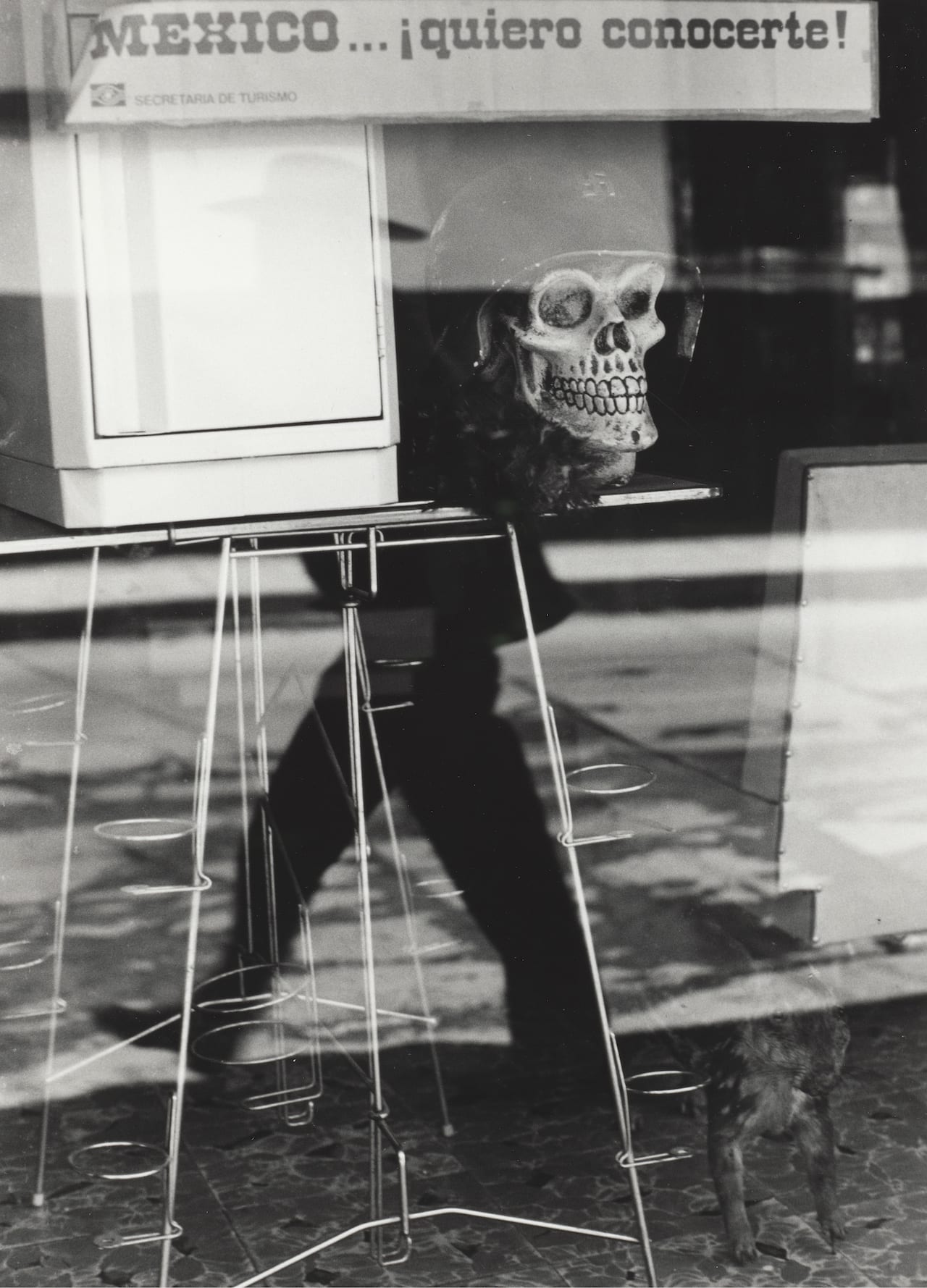

Behind a shop vitrine, a human skull, wearing a helmet adorned with a swastika, grins. Next to it, an animal – apparently taxidermic – stands rigid on the floor. The silhouette of a pair of legs belonging to a passer-by on the street reflects in the glass. Above this desultory display, a banner stuck to the top of the window reads, “Mexico… ¡quiero conocerte!”. In this single photograph, taken in 1975 in Chiapas, Graciela Iturbide projects her vision of Mexico: a country of political, religious, social, cultural and economic pluralities and tensions. A place where contrasts present themselves at every turn – sometimes harmonious, sometimes tense.

It is this multilayered image of Mexico that Iturbide has slowly peeled back and revealed through her photography over the last five decades. She has travelled extensively across her own country, between urban and rural landscapes, living with different communities, and moving from the physical to the transcendental, the ancient to the contemporary, witnessing and experiencing the juxtapositions intertwined in Mexican culture.

Very well known across Latin America, but less widely celebrated internationally, Iturbide – a former assistant to Manuel Álvarez Bravo in the early 1970s – is finally revered in the US this year, with a major exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on show from 19 January to 12 May. Titled Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico, the exhibition includes 37 rare and vintage prints recently acquired by the museum and shot between 1969 and 2007, surveying Iturbide’s profound and continued study of her own country.

The show comes in the wake of Donald Trump’s declaration of anti-Mexican racism during his 2016 presidential campaign, painting an image of Mexicans in hateful words, backed by the promise to build a wall along the country’s border. “I am very proud to present this work in the United States at this time,” Iturbide says of the timing, given the works in the exhibition focus solely on her work in and around her homeland. “I totally oppose the racism that the president and some Americans have shown – fortunately there are many American people who admire Mexico.”

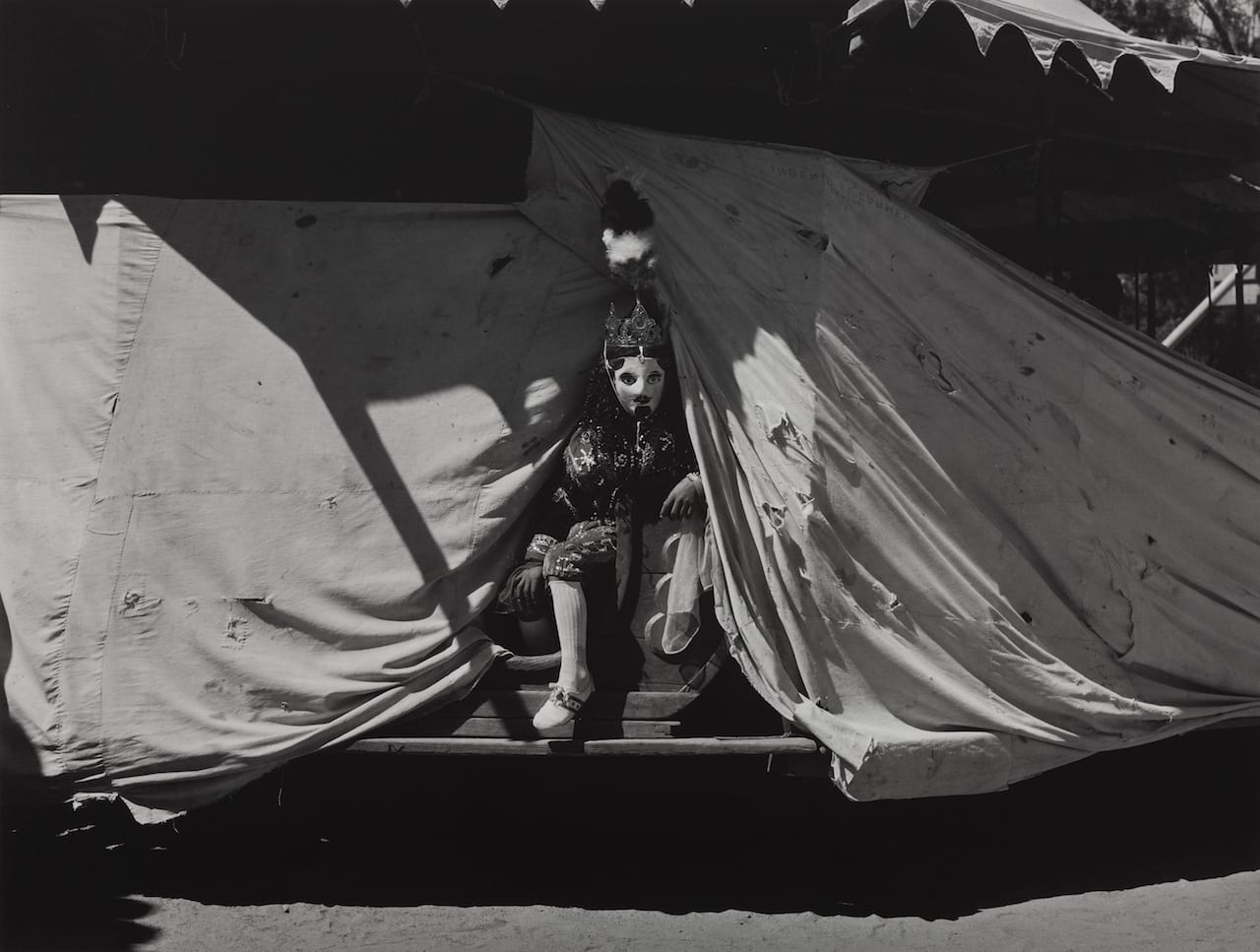

Photography has often been used to construct a false narrative of national identity, as viewed by a foreign gaze. A country as large and varied as Mexico – a hybrid of indigenous and colonial culture, mediated by religion and traditional rituals, where more than 90 indigenous languages are spoken and more than 129 million people of different ethnicities live, is impossible to reduce to a single image. It is a place where you are constantly confronted with the richness of life and where you are firmly rooted in the present moment – something Iturbide captures in a style that is both cinematic (she originally studied filmmaking) and documentary, a dance between dreamlike and macabre.

One thing she avoids is the exoticisation of the strange and unusual aspects of what she witnesses. “I do not like Mexican stereotypes, but unfortunately many photographers who come from abroad and who have not understood my country fall into this error,” Iturbide says. “I have tried to live with the people of my country and get away from these stereotypes that hurt us.” Her approach to Mexico rails against the constructed perspectives of outsiders. “I have always said that my camera is a pretext to know the culture, its people, and the way of life,” she explains.

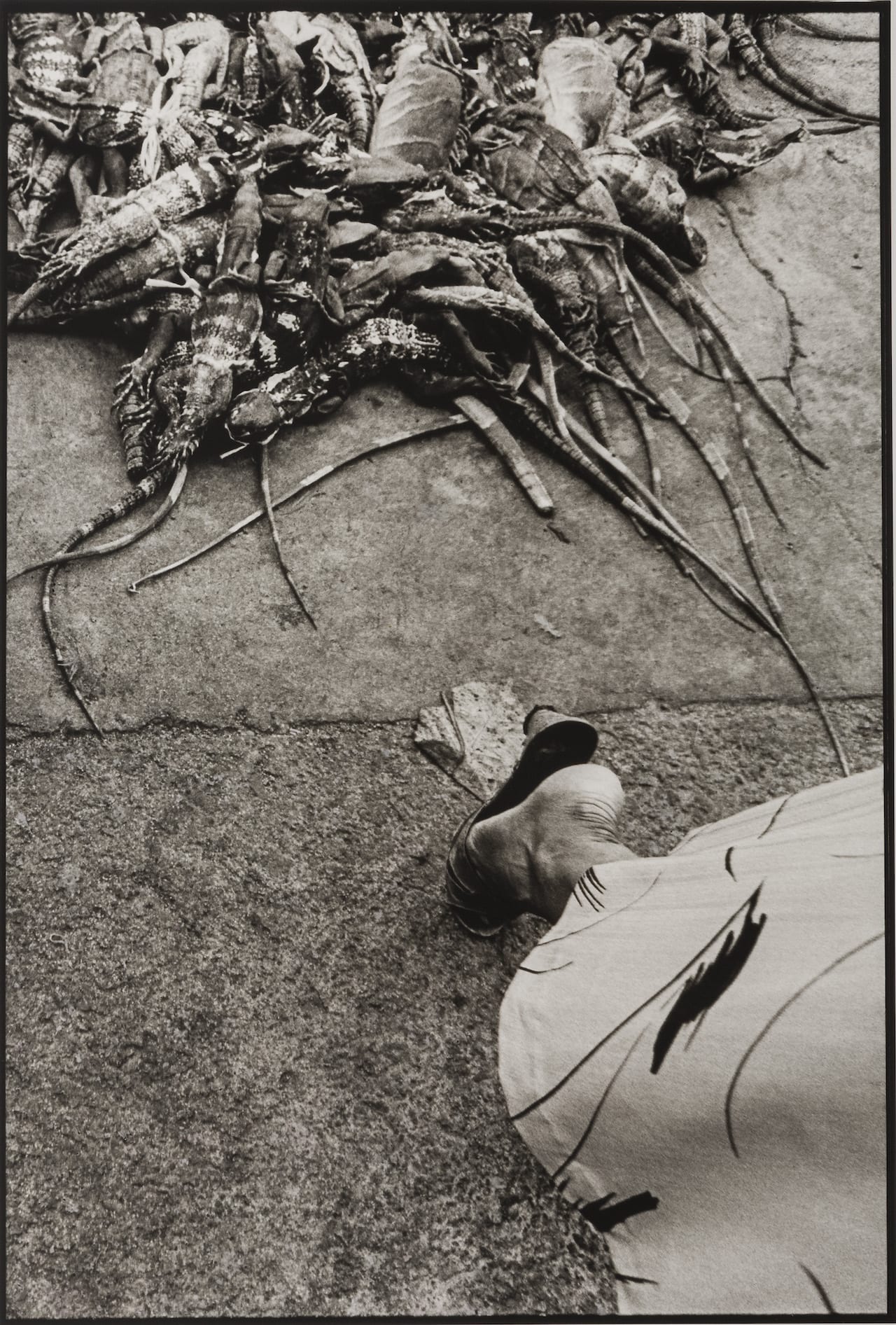

Yet she has been an outsider in her own nation too. Although born and raised in Mexico City, Iturbide’s life was different to some of the indigenous people she has photographed – including the Seri Indians, a group of nomadic fishermen from the Sonoran Desert, close to the border with Arizona, and the Juchitán people, who form part of the Zapotec culture native to Oaxaca in southern Mexico. She spent almost a decade photographing the Juchitán, initially as a commission for Francisco Toledo, in 1979. It has become one of her most famous bodies of work – published as a book in 1989.

“I’ve travelled my country and I’ve learned from it,” she affirms. “I’m very proud to be Mexican and I have tried to have complicity with all the people I photograph. I have lived with them to understand and respect their traditions and their daily lives. I photograph with the surprise of what I find and the passion that I have in my work and I learn the different ways of living in my country.” She photographs her country in order to understand it, in order to acknowledge her own history and heritage – not without criticism of the inequalities and politics she observes, but with a deep and evolving love for her native land.

Redefining the image of Mexican women, in a country where the roles of women are still shaped by both religion and custom, has also been a consistent interest in Iturbide’s work. In one later photograph, she addresses an icon, Frida Kahlo. Rather than giving us the image we know too well – the face that’s been printed onto a thousand objects, from pillowcases to tequila bottles – Iturbide reminds us of Kahlo’s suffering, and what she had to overcome: a simple picture of her self-fashioned prosthetic leg, propped against a wall. This is the Frida that Iturbide wants us to remember.

Iturbide preserves the nuances of the Mexican past in her photographs, but they also undoubtedly speak to the present with a renewed sense of purpose. “My work, good or bad, represents the way of life of my compatriots from whom I have learned a lot and with whom I have shared wonderful times,” Iturbide adds. “For a time, I also photographed migrants who had been mistreated unjustly, and I have lived in East LA and elsewhere, with Mexican workers born in the United States, where the racism to which they are subjected is evident. Hopefully one day this racism ends, so we can live together peacefully.”

The museum’s decision to focus on Iturbide’s exploration of Mexico is careful and deliberate, and positions her among the likes of Helen Levitt, Diane Arbus or Susan Meiselas, who all confronted their own people with their camera in an attempt to also frame their own identity and relationship to their country and its culture. In dialogue with the most famous images of Mexico in the 20th century – such as those taken by Paul Strand or Edward Weston – this personal connection is abundantly clear.

“Iturbide sees her country from a different vantage point than many of those who have contributed to Mexico’s visual heritage,” reflects Kristen Gresh, the MFA’s curator of photographs. “It is a heritage complicated by foreigners who have influenced Mexicans’ perception of their own country.”

During the curatorial process, Iturbide granted Gresh unprecedented access to her body of work. After three years of working on the exhibition, the curator maintains that the work is not directly responding to today’s political climate, but agrees that over the years it has “become even more relevant and timely”, and an important counterpoint to the nefarious image of Mexican people promulgated by the US president.

“Iturbide’s documentary work goes beyond the role of bearing witness and provides a poetic vision of contemporary culture informed by a sense of life’s surprises and mysteries,” she notes. “I hope that her powerful and provocative photographs will inspire visitors to learn more about and better understand our Mexican neighbours.”

gracielaiturbide.org Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico is on show at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from 19 January to 12 May www.mfa.org/exhibitions/graciela-iturbides-mexico This article is taken from the February issue of BJP www.thebjpshop.com