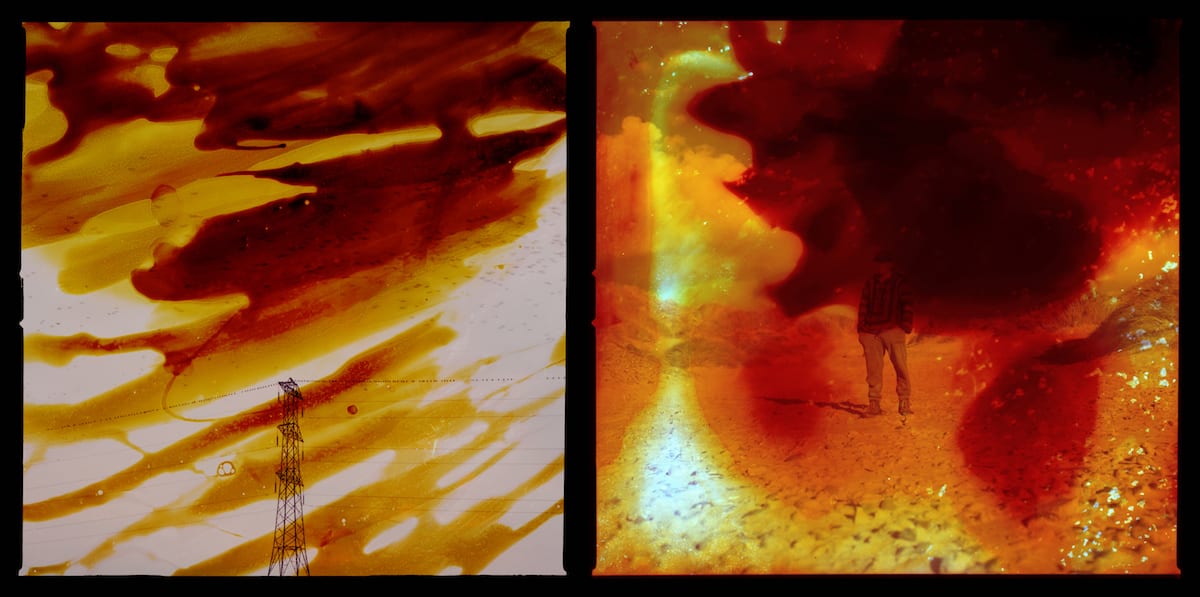

For Fractured Stories, a British Journal of Photography commission supported by Ecotricity, Rhiannon Adam spent four months immersed in the fracking debate. A series of editorials published on BJP-online tell the stories of the individuals she encountered. A number of images are corrupted with a constituent chemical of frack-fluid, alluding to the potential environmental impacts of the practice. The last in the series sheds light on the lives of anti-fracking campaigners.

“So often on Preston New Road, a car will pass and someone will shout: ‘Get a life, get a job, have a wash’,” says Rhiannon Adam, recounting the kind of insults routinely hurled at anti-fracking campaigners demonstrating at the UK’s first operative fracking site. Earlier that day, Adam travelled to Manchester to visit Anne Power, an 87-year-old anti-fracking activist, at her home in an outer suburb of the city. Turning onto Anne’s road, Adam spots a bright red car emblazoned with the words ‘No Fracking’ in front of a terraced house. “I thought I was in the wrong place until I saw it,” she says.

“Meeting someone on the roadside at Preston New Road is very different to seeing what cups and saucers they have, or what colour scheme they have in their house,” says Adam. The interior of Anne’s house is dazzling: “She wanted the house to flow; it looks as though an interior designer has decorated each individual space.” Anne built the stairs and knocked through the property’s walls herself. For decoration, she salvaged and repainted objects from skips, collected bits of brick and glass, and made collages.

“If I am just photographing someone at a protest, I don’t really get to see who they are,” says Adam. “They are just a number, a body, a presence on the street, which is, of course, important, but it is much more important to be able to understand someone’s actual motivation.” Visiting her subjects at their homes across the country enabled the London-based photographer to do this. “It is important to understand someone’s background” she continues, “to understand the richness and depth of their personality.” At home, one is always more at ease: there is the opportunity to discuss a subject’s backstory, to understand more fully what led them to become involved in the anti-fracking movement. “You really appreciate with someone, like Anne, how much she has seen and how much she has lived,” says Adam. “She has been alive for so long; the fact that she thinks this is an issue worth caring about says something.”

Since September, Adam has immersed herself in the UK fracking debate. She spent much of her time at, and around, Preston New Road in Lancashire, home of the UK’s first active fracking site since a moratorium on the practice was lifted in late 2012. The first frack took place on 15 October 2018, midway through Adam’s project. The process has caused numerous tremors to date. A number of which have stalled operations in line with government regulation. Many of the campaigners she encountered at Preston New Road are locals or residents of the two permanent protest camps just feet from the main site; others, like Anne, are drawn from further afield.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, as it is more commonly known, is a controversial process used to extract oil and gas trapped in shale, and other, rock formations. It involves drilling down deep into the earth; a mixture of water, sand and chemicals is then injected at high pressure to fracture the rock. The gas released travels into the water stream and either flows back, or is pumped, to the surface.

Fracking is more common in the US where it has revolutionised the energy landscape: over 100,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled and fracked in the country since 2005. Despite Europe being projected as the new fracking mecca, it has been largely unsuccessful. The process is not permitted in France, Germany or Bulgaria; Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have all placed their own suspensions on it.

In the UK, fracking first came to national attention in the spring of 2011 when Cuadrilla fracked at a site in Preese Hall in Weeton, Lancashire, causing earthquakes; a moratorium was subsequently imposed until late 2012. Public opposition resurfaced in 2013 as protests sprang up around a proposed site near the West Sussex village of Balcombe and the drilling of a well at Barton Moss, Salford. Preston New Road became the focal point of the fracking debate after Cuadrilla applied to drill there in 2014.

Opponents stress the potential environmental impacts: earthquakes, pollution of water supplies, water wastage and air pollution. Other concerns include, noise pollution, the industrialisation of the countryside and a detrimental effect on house prices. Ultimately, it represents a continued investment in fossil fuels at a time when eliminating our reliance on them is crucial.

Advocates for the practice point to its potential for job creation, along with its ability to offer us energy security and act as a ‘bridge fuel’ to a renewable energy future.

Anne made headlines in 2017 when police dragged her across the road outside the Preston New Road fracking site after she refused to move from the entrance. Footage of her being pulled along the tarmac by three policemen was featured by many major media outlets. In summer of 2018, the actions of three activists received similarly widespread coverage. Simon Roscoe Blevins, Richard Roberts and Richard Loizou were convicted for engaging in a lock-on that lasted almost 100 hours in July 2017 and were each sentenced to between 15 and 16 months in prison. They were later released after six weeks when the court of appeal ruled that their sentences were ‘manifestly’ excessive, and the original judge’s family links to the oil and gas industry were brought to light.

Like Anne, the coverage of Blevins, Roberts and Loizou was centred on their activities at Preston New Road. Driven to know more, Adam travelled to visit Blevins at home in Sheffield and Loizou in London. Below, her images shed light on the stories of these three campaigners.

–

Simon Roscoe Blevins

“We are out of prison, in part, because we are outspoken, educated, middle-class, white-people. If we were not, then the media and the general public might not have taken so kindly. This is not just or fair”

Simon Roscoe Blevins, 26, has lived in a housing co-op in Sheffield for the past two years. He studied an MSci in Plant Sciences at the University of Sheffield, where he now works as a research technician. “My MSci was a significant turning point,” he says, “through your research you are aware of what is at stake and you feel the need to start putting yourself on the line for it.” The development of a number of proposed sites near his hometown, including one at Tinker Lane, also spurred Roscoe into action.

Roscoe did not plan to climb on top of the lorry, delivering equipment to Preston New Road, which saw him and two others sentenced to 16 months in prison. He was later released after the Lord Chief Justice ruled the sentence was “manifestly excessive”. “It was a split-second decision,” says Roscoe, “I climbed up expecting to be taken down within one or two hours by the police. No one came so I stayed. Still, no one came, so I stayed.” He remained on the lorry for 73 hours.

“The most striking thing was the unique perspective it gave me,” he says. “Being elevated allowed me to see how many people are involved and how many people care about fighting this.” The support offered by fellow campaigners and locals was incredible. “Residents from Carr Bridge Park, where lots of elderly people live, came over and offered support – from blankets and jacket potatoes to their thanks,” he remembers.

Roscoe remains dedicated to the anti-fracking campaign. “We need to stop framing fracking as a singular issue,” he says. “People often start protesting through nimbyism. But, through getting involved they learn more about climate change and realise that fracking is part of a much bigger issue.”

–

Anne Power

“I am very prone to get angry; that saves me from getting scared”

“I did not realise that this was going to change my life so fully,” says Anne Power. “I have got to 87 [she was 85 at the time of the incident] without ever being injured on the road; I know how to manage things for heaven’s sake.” Anne’s grandfather was a policeman. He died after sustaining injuries while saving children from an oncoming cyclist. “I had such a respect for the police,” she says. This is no longer the case.

Anne has been demonstrating against fracking for the last five years. At least twice a week she drives to Preston New Road from her home in Manchester. Often, she travels through the night to ferry people from site to site. In summer 2017, she spent four nights in her car on the roadside, just beside Preston New Road. A group of protectors built two towers at the gate. “I was watching while I was dozing; I couldn’t tell whether they had built it on the bonnet of my car or not.”

“I have done things that I would have never expected,” says Anne, who originally trained as a teacher. Disillusioned by the curriculum, she retrained as a personal counsellor and started her own practice in 1981 in a small cottage in the hills of Lancashire. That same year she joined the Green Party. “My life dovetailed in that way: I found a political philosophy for the first time and a personal philosophy that really suited me.” Today, Anne devotes the bottom floor of her house to the activities of Party members.

“I got involved in the fracking resistance because it started at Barton Moss, very near to where I live.” she says. “I had just moved house and had the stair carpet laid. I went to an anti-fracking meeting in Eccles; the next day I went to the protest camp and from then I was just there every day, relentlessly. I never finished moving into my house.” This year, Anne has, in her own words: “focused on making more of a nest.”

–

Richard Roberts

“There is so much need everywhere. It can be so overwhelming that the temptation is to do nothing”

Richard Roberts is a piano-restorer based in London; he specialises in reviving old, neglected pianos: “It’s a trade my father taught me, and his grandfather before that.” Roberts has been deeply concerned about the state of the environment for years and devotes much of his time campaigning to protect it; he has made adjustments to his personal life in line with his beliefs. “I had a vasectomy three years ago because I don’t think that the world needs my kids,” he says. “What it needs is more volunteer work and, since I’m a rather slow chap and rubbish at multitasking, I didn’t think I’d be able to support a family and do much volunteering at the same time.”

Roberts felt frustrated and disempowered by the speed and scale of planetary destruction until he met Reclaim the Power: a UK-based direct action network fighting for social, environmental and economic justice. The movement, which is open to anyone, works in solidarity with frontline communities to effectively confront environmentally-destructive industries and the social and economic forces driving climate change.

In July 2017, Reclaim the Power hosted a month of action at Preston New Road as it became increasingly apparent that attempts to challenge fracking through democratic and legal avenues had been exhausted. “Industry and government PR always serve up the same old line: ‘We need gas to heat our homes. If we don’t frack for it, we’ll have to import it, which is not good for our energy security or our economy,’” he says. “But we all know that we need to rapidly wean ourselves off fossil fuels now to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change.” Roberts outlines the myriad alternatives, including improved housing insulation and renewable energy. “I could see that this was the first of potentially thousands of fracking sites, locking another generation into fossil fuel dependence, so it was important to send a strong, deterrent message that the UK government needs to change tack on energy policy,” he says.

Alongside Blevins, Roberts was one of the two other campaigners who climbed on top of a lorry delivering equipment to Preston New Road during Reclaim the Power’s month of resistance. The action was wholly unplanned and saw him sentenced to 16 months in prison in September 2018; he was swiftly released. Roberts has since become a spokesperson for the anti-fracking moment. “[I feel] undeserving and unqualified,” he reflects. “Hundreds of people made it possible for dozens of people to stop that convoy of fracking equipment for four days … many of them are much better spokespeople than I ever will be!”

Read the introduction to the project here; the first article, which offers a glimpse into life on the frontline of the fracking resistance, here; and the second, which tells the stories of local people both for and against the practice, here.

–

“These pictures are dedicated to Thomas Burke, who sadly passed away on the 7th of January 2019, and all those like him, the so-often unsung heroes and heroines of frontline activism. We need more people like Tom.

Tom was a constant fixture during my time at Maple Farm and PNR – always welcoming, and interested in what I was up to. Though he may have seemed quiet at times, he had a mischievous sense of humour, topped off by a truly generous spirit. Few outside of the activist circle realise how much self-sacrifice goes into living on the front line – the hardship that comes with it, the discomfort, the cold, the stress, the emotional toll. Every day, people like Tom put their lives on the line in a belief that our collective future is worth fighting for. Of course, there is also the camaraderie and collective strength – to those at PNR, losing Tom is like losing a family member, and I know that his loss cuts deeply. Wishing strength to all those who knew and loved Tom / Grandad Tom.” – Rhiannon Adam

–

Fractured Stories is a British Journal of Photography commission made possible with the generous support of Ecotricity. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.