In 2011 Nigel Poor, a professor of photography at the California State University, began volunteering at the San Quentin State Prison, just north of San Francisco, as a photo history instructor in the prison’s college programme. Two years later, she moved over to work with incarcerated men in the existing prison radio station, but concurrently pulled on her background in photography.

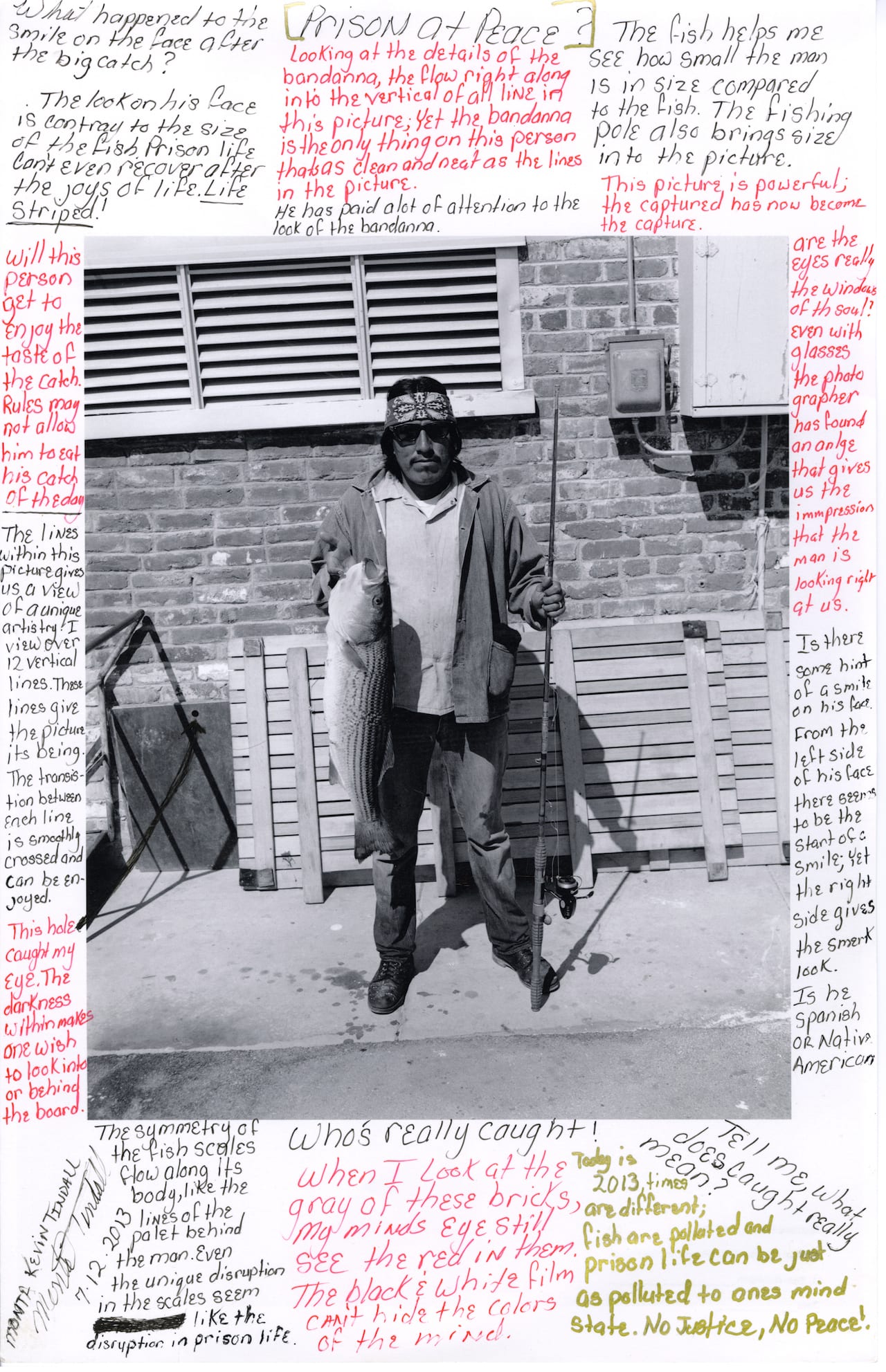

In an exercise Poor calls “mapping”, she asked prisoners to annotate famous photographs. Works by Lee Friedlander, David Hilliard, Stephen Shore and others were pored over by prisoners, resulting in text-laden replicates. These creative brainstorms have been preserved, and now hang on wires sandwiched between glass as works of art, in the first room of an exhibition on show at the Milwaukee Art Museum until 10 March, titled The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison.

Of the many thrilling aspects of the show, the fact that a podcast takes place alongside the prints in the galleries is perhaps the most exhilarating. But given Ear Hustle’s (the non-fiction audio series produced at the prison by Poor and two inmates, Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams) meteoric rise in popularity – 17.5 million downloads and counting – and the way it has enraptured audiences since its launch in 2016, we should not be surprised. Nor should we be in any doubt of the podcast’s rightful place within an art museum context. After all, audio and photography are both mediums beholden to narrative.

Still, it took brave stewardship by Lisa Sutcliffe, MAM curator of photography and media arts, to steer this rich mix of fine art, prisoner-made text pieces and the Ear Hustle episode archive. Poor, whose nimble, cross-media art practice is brought together here, says Sutcliffe and her exhibition design team were full collaborators in the compelling installation that she considers an artwork in itself.

Archive photographs of San Quentin fill the second room – many of these also annotated by prisoners’ interpretations. When Lieutenant Sam Robinson, the prison’s public information officer, showed Poor a box of untouched 4×5 negatives, her “heart just exploded”. It had the potential to be the first revelatory moment of the all-too-common lost archive discovery narrative beloved by the media, but Poor’s thoughts turned not to publications on the outside but her students and colleagues on the inside.

Poor was permitted to take home an envelope of about 100 negatives – pictures taken by prison-appointed photographers, usually corrections officers, dating from the late 1940s to the late 1980s. She printed a few dozen on large card stock with wide white borders in which the incarcerated men could write their observations. These “mapped” prison images are compelling; the men are prison experts and draw out details that the layperson simply would not notice. Exhibition attendees stood for noticeably long times reading as well as looking. “And talking to one another,” says Poor, “which is always a good sign.”

On an adjacent wall, a new and exclusive selection of prints depicts a range of scenes, from the very normal (an amateur rock band, a football team photo, graduation pictures, religious observance) to the bizarre and inexplicable (medical examinations, baby seal pups, crime-scene re-enactments, macabre anonymous portraits). Even the most confounding of these decades-old jail pictures can be deciphered – we need only to follow the prisoners’ examples on the other side of the room.

Third, and finally, is a room devoted to Ear Hustle and to a library of suggested books and reading. Listener stations offer every episode to gallery-goers. A video of sound designer Antwan Williams interviewing Poor’s co-host Earlonne Woods is also here. Despite the brutal statistics and recent history that underpin mass incarceration in the US, The San Quentin Project is not depressing. There’s too much personality and unexpected perspectives for visitors to walk away disconsolate.

There might also be a huge lesson for young artists too. While photography invariably needs story, story does not always need photography. Poor entered the story-rich San Quentin community as a teacher focused on photography, but has transformed into a collaborator, colleague and equal of men on the inside and together they’ve produced audio that’s downloaded to millions of devices worldwide. The San Quentin Project humbly and lovingly puts photography in its place.

The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison is on show until 10 March at the Milwaukee Art Museum mam.or This article was first published in the January issue of BJP www.thebjpshop.com