An interview with Don McCullin is never going to be a dull affair – he is a complex man who has told the story of his life many times before. He is unfailingly polite and gentlemanly, but one detects a slightly weary tone as he goes over the familiar ground. He often pre-empts the questions with clinical self-awareness.

The story of McCullin’s rise from the impoverished backstreets of Finsbury Park in north London is one of fortuitous good luck, but it didn’t start out that way. Born in 1935, he was just 14 when his father died, after which he was brought up by his dominant, and sometimes violent, mother. During National Service with Britain’s Royal Air Force, he was posted to Suez, Kenya, Aden and Cyprus, gaining experience as a darkroom assistant. He bought a Rolleicord camera for £30 in Kenya, but pawned it when he returned home to England, and started to become a bit of a tearaway.

Redemption came when his mother redeemed the camera, and MccCullin started to take photographs of a local gang, The Guvners. One of the hoodlums killed a policeman, and McCullin was persuaded to show a group portrait of the gang to The Observer. It published the photo, and kick-started a burgeoning career as a photographer for the newspaper.

“That gang picture was the ticket to rest of my life,” McCullin reminisces. “£5 was the cost of my life as a photographer – that’s what my mother paid to redeem the camera I had pawned.” Did she have an instinct that the camera would be his making? “I don’t know, she was a complex woman,” he replies.

His time with The Observer was a mutual culture shock. He had entered what was essentially a middle-class world populated by university graduates, many of whom had never encountered the rough edges of a street-wise north London lad. But, “I wanted to learn. I watched how things were done in that world,” he told the BBC. “I realised I had to reinvent my life, shuffle about finding ways to educate myself.” An interviewer once described him a “not a learned man”. Amused, he responded, “But I have spent my life doing my best to learn.”

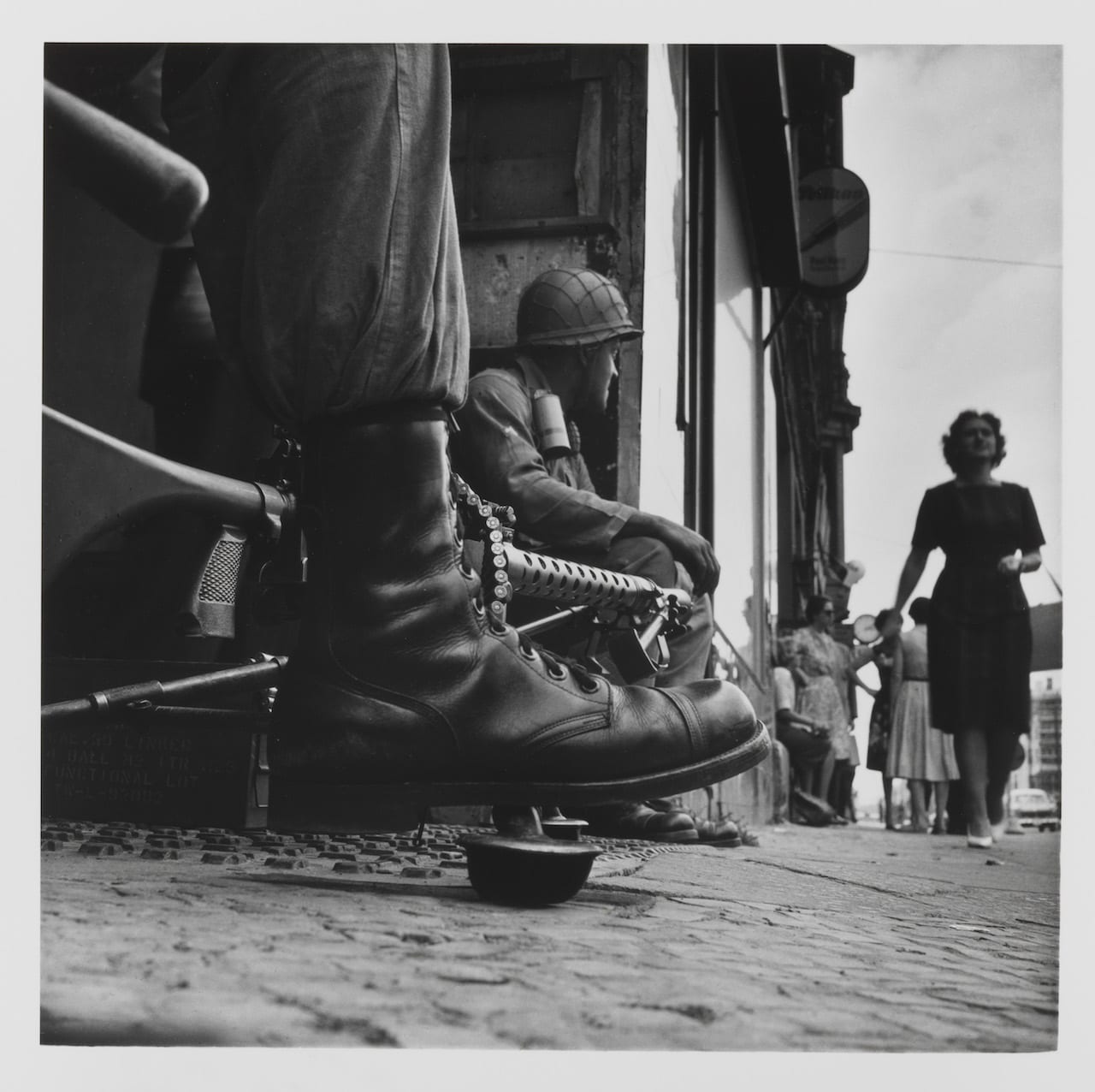

In his late 20s, McCullin developed a taste for foreign stories. Without being commissioned, he took himself off to shoot a story on the Berlin Wall, after seeing the famous news picture of an East German soldier leaping to freedom in the West. In 1964, The Observer asked if he would like to cover the civil war that was hotting up in Cyprus. McCullin was elated. It was his first real foray into a conflict zone and the photographs he produced were remarkable, arguably still some of his finest work. They catapulted him into the international arena of photojournalism.

He subsequently spent 18 years with The Sunday Times Magazine, at a time when the publication was one of the world’s most respected outlets for reportage stories. It was a buoyant and successful time for the publication, and McCullin was very much part of its culture. He talks of the magazine’s art department as “the best place in the world, full of genius”, and refers glowingly to the art director, Michael Rand. He recalls, almost incredulously, how the art editor David King (now better-known for his vast collection of Soviet Russian-related imagery) once laid out 18 pages of his work on Cuba.

Rand for his part tells me that McCullin was the perfect colleague. “He didn’t need briefing,” he says. “When he was not away on assignment, he would hang around the office, worrying about where he should go next. If he got interested in a story, I would say, ‘Why don’t you go?’ There was never any question of not sending him where he wanted to go.”

Yet McCullin remained his own man. “I always gave the art department a very tight edit, and they never asked for more,” he says. “They trusted me – after all, I had risked my life on many occasions for them and I’d earned the right to make my own selection.”

Rand confirms that McCullin was an excellent and ruthless editor of his own work, something rarely the case with photojournalists. Even so, McCullin admits to overlooking one of his most famous and iconic Vietnam images – the close-up of a shell-shocked American soldier. Arriving back from Vietnam exhausted, he was in a hurry for a deadline. “I was too busy looking for the action pictures and missed it. It taught me a lesson.”

Harold Evans, editor-in-chief of The Sunday Times while McCullin produced his finest magazine work, places him alongside Robert Capa, Larry Burrows and Philip Jones-Griffiths as one of the greatest war photographers ever. Rand agrees, adding: “He has a particular eye. He worked best in extreme situations, on stories that had a certain edge, social stories about the human condition, like the genocide of the Brazilian Indians. He was not shooting news stories, more a personal view of the conflict. Not what happened, but what it was like.”

Rand feels that the plight of the poor and dispossessed brought out the best in him, and Evans agrees. “He cared about the victims, the ‘collateral damage’,” he tells me. “He couldn’t express it in words but he expressed it in his photography.” McCullin himself attributes his capacity for empathy partly to his own harsh childhood, which included some miserable experiences when he was evacuated during the war.

Nevertheless, McCullin now seems ambivalent and uneasy revisiting those heady magazine days. Talking to the photographer Frank Horvat, he recalled: “When I came back to the office and showed the pictures, they would say, ‘God, that’s terrible – make it a double-page spread’, or ‘That’s awful, it’s a good cover’. And I didn’t mind because it gave me an opportunity to go to the next war.”

In 1982 Evans resigned from The Sunday Times, citing differences over editorial independence. He was replaced by Andrew Neil, who dismissed McCullin the following year after the photographer publicly complained about the newspaper’s lack of serious foreign and social coverage.

McCullin displays a lacerating tendency to be hard on himself. “Must you mess around with other people’s lives for your own career?” he muses. He is much taken with a phrase used about the legendary Magnum photographer, Eugene Smith, who was described as having “nerve ends hanging out of his finger tips”. He worries that he himself lacks an appropriate sense of feeling. “When I see terrible things, I don’t always get upset…It’s an emotional weakness,” he concludes.

His great hero, Henri Cartier-Bresson, once likened his work to Goya, but McCullin dismisses the accolade. “I have a strong creative desire but I’m not trying to be an artist. I don’t need titles. I hate the title, ‘artist’. I just describe myself as a photographer.” He prefers to pride himself on being a professional craftsman. “I have a good nose for news. It’s about knowing your trade. There’s no confusion in my approach. I’m not wide-eyed, I’m precise, direct. I work to a set of rules, ethics. I don’t like wasting film. I have respect for film.”

Unlike the popular image of a war photographer, McCullin was never gung-ho or flash. He went into conflict zones with little equipment in a low-key, unostentatious way. He learnt quickly, as a first priority, how to extricate himself from tricky situations and, just as importantly, how to smuggle his film out if necessary. The writer James Fox said, “Don always knows when to leave, when to stay”, something which McCullin echoed to Horvat.

“A sense of timing is the most important part of the life of a professional photographer,” he said. “I have an uncanny way of being at the right place at the right time. And if the time is not right, I can be patient, stay in that place for hours, willing things to come.”

He shakes his head sadly at the recollection of an inexperienced photojournalist, Gad Gross, who was killed near Kirkuk during the first Gulf War in 1991 when the Iraqis counter-attacked. McCullin decided that it was too dangerous to hang around and moved out, but Gross stayed on and was killed the next day. “He couldn’t read the signs,” says McCullin.

He doesn’t have much time for the conceptual approach. “If you try to direct the world with your mind, you won’t come up trumps. Out in the field, it’s all about having the nerve to wait. Most of my conflict photographs are full frame, not cropped. It’s all about discipline.”

Evans recalls a photograph taken in Cyprus, in which McCullin caught a woman at the very point of hearing of the death of her husband, being comforted by her young son. “The elements of that touching photograph lasted a fraction of a second – but McCullin did not shoot it from the hip, he took a light reading.”. “I always do,” the photographer tells me. “Even in battle photography I go over on my back and read the exposure. What’s the point of getting killed if you’ve got the wrong exposure?”

McCullin is searingly honest about the addictive side of war photography. “It gives you excitement, a tingle, a buzz. And fear, too.” He has admitted he “used to chase wars like a drunk chasing a can of lager”. But while he has made occasional forays into war zones during the past 20 years or so, he has concluded with distaste that the ability to work as an independent photojournalist has all but disappeared. He refuses to operate in a pack and is scathing about the embedding of photographers in current conflicts, unable to envisage how he would cope with the controls and restrictions.

After the invasion of Iraq, he was stuck on the northern border with John Simpson of the BBC and hated being there, having to wait for permission to cross over. He never wanted to be chaperoned, even by guerrilla groups. “They steer you away from the truth.” After the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, he spent time with the Mujahideen and it was “useless”. “All they wanted to do was show me bombed-out Russian tanks.” His eyes light up when he discusses how relatively easy it was to work in Vietnam. “You could always hitch a ride with the military and if you weren’t getting what you wanted, it was very easy to move on.”

But, looking back, two lost opportunities in his professional career continue to cause him grief. He was desolate when he was refused press accreditation to cover the Falklands War between Britain and Argentina in 1982, assuming that the-then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had banned him because his photographs might prove too disturbing politically. Very recently he found out that it had been an innocuous administrative decision by the Royal Navy which had already allocated its available press slots. “Bureaucracy is the worst religion,” he growls.

And when the world first heard about the massive famine in Ethiopia in 1984, McCullin was bitterly disappointed that The Sunday Times didn’t send him on the story. “I should have gone on my own, jumped on a plane by myself,” he says. “It showed me up.” He confesses to having been jealous of Sebastião Salgado’s photographs of the famine, which received worldwide acclaim. “I was at my best then. Salgado deserved his praise but this story was made for me. I was left at the bus stop.”

Being a prisoner of Idi Amin was unpleasant. He was in the hotel swimming pool, waiting for a flight out of Uganda when Amin’s goons came for him and some other foreign journalists. “They took us to a notorious prison where hundreds of prisoners were being sledge-hammered to death every day. We were kicked and beaten with sticks. It took four days for the British High Commission to get us out of there.”

Yet his very worst day was not at war but when his first wife Christine died, something he wrote about so painfully in his autobiography, Unreasonable Behaviour. She was found dead on the day of his son’s wedding. “This was a drama bigger than any war,” he says. “Here was a body in my own house, not on some distant battlefield. Christine was taken out in a body bag – it was like some awful stage production. I was not prepared for this on my home patch.”

McCullin has only ever set up one photograph, and that was for a purpose. This was his famous picture of a dead Viet Cong soldier surrounded by his few possessions. “There was a kind of insanity in the air, there had been day after day of bloodletting,” he recalled. “I came across the body of a young Viet Cong soldier. Some American soldiers were abusing him verbally and stealing his things as souvenirs.

“It upset me – if this man was brave enough to fight for the freedom of his country, he should have respect. I posed him with his few possessions for a purpose, for a reason, to make a statement. You see, I’d developed a mind by then, I was my own man and I’d got attitudes. I felt I had a kind of puritanical obligation to give this dead man a voice.”

One picture above all seems to have seared itself into his mind, taken in Beirut in 1976 and showing six right-wing Phalangist fighters, one holding a lute, mockingly serenading the body of a dead Palestinian girl. “It was a very menacing atmosphere. The Phalangists were massacring Palestinian civilians and I had been told to leave the area. But these guys called me over to take a picture. I shot two frames without taking a meter reading and got out of there”. Later, he was stopped at a Muslim checkpoint by left-wing gunmen who threatened to cut his throat when they found he was in possession of a Falangist press pass.

Beirut, too, was the scene of one of the most disturbing things that happened in his life. An Israeli bomb had flattened an apartment block and a Palestinian woman came round the corner hysterical with grief, knowing that all her family were inside. McCullin took a picture of her but she started screaming at him, beating him with her fists. Someone pulled her off him but another Palestinian tried to grab his camera, holding a 9mm pistol to his head. He got away, but was in deep shock.

Rather than fear, what he remembers is the humiliation of the event, witnessed by hundreds of Palestinians. “I had been too quick for my own good, my judgement was wrong. I deserved to be attacked by this woman.” Later that day, someone told him the same woman had just been killed. “At that moment, the pleasure of photography was stolen from me.”

In spite of fame and all the plaudits, McCullin displays palpable anxieties and self-doubts. His biggest fear remains that he might fail on an assignment. He even dreams of this failure, worrying about the loss of face, the gossip among his fellow photographers. Michael Rand confirms this insecurity. “He was constantly worried about whether he had got the story. He had no fear of going into danger zones but had this terrible fear of failure. He told me once that he would sometimes vomit with anxiety flying to a difficult assignment.”

Whenever he gives talks about his work, he is always asked, “Have you ever stopped being a photographer, put down the camera and helped people in trouble or danger?” He recalls the best photograph he never took, while working on an AIDS story in Zambia. “I went into a hut, the conditions were terrible. A woman was lying on a stinking mattress cared for by her sister. We’d just come from a hospice where there were empty beds and so we suggested she should be moved there.”

McCullin went up the road to hire a van from the local market. While he and the driver were arranging the back of the van, he saw the woman struggling out of the hut carrying her sick sister on her shoulders. “My camera was in my bag, so I missed a great shot because I was doing something more important. I could have asked her to do it again but I didn’t because I would have felt no pride in such a reconstruction.”

In these later days of his life, McCullin is preoccupied with the landscape and nature around him in Somerset, in the West of England. He has described his love of landscape as “herbal medicine for my mind”. He is scornful about fame, comparing it, tellingly, to a “smelling body”, but is honest enough to admit he enjoyed it when it came to him in the past. He says he has not become rich out of photography, but is rich in lifestyle, taking spiritual energy from his life in the countryside.

“Who wants a house full of dying people, 6,000 prints of dying people amidst all this tranquillity?” he asks rhetorically. He mentions in passing that he has been made a substantial offer for his archives from the US, so perhaps these residual ghosts will be spirited away.

His body is in pain now from arthritis and he has eye trouble, a curse for a photographer. Worse, he suffered a stroke in March 2009, and this restricts the energy he can devote to photography. A recent two-year project on Roman relics took a lot out of him. He had a bad fall and discovered four weeks later that he had punctured his lung. “I don’t dwell on it, I try to ward it off,” he says, talking of his health. “All I want is another five good years with my son, Max.”

Escaping from Finsbury Park was undoubtedly a strong motivational force in McCullin’s life, but he refutes the suggestion that his career was a product of the class war. “I don’t want to wave that flag for the rest of my life,” he says. “I got rid of my inferiority complex 20 years ago. I want to be recognised for my own achievements.”

He talks of the world of his childhood as one of violence, bigotry, pain, and a complete absence of books. “I haven’t squandered the privilege of being taken out of my background. Growing up, I was an urchin, but I stopped being a blind boy from Finsbury Park without culture and music.” He now has a passion for classical music, listening to it in his darkroom, and he can hum his favourite pieces by heart. “I feel at the edge of my journey with photography now. I’m older, more knowledgeable, but I’m never satisfied, never arriving, always looking for something better to come. I’m a lost soul without photography.”

McCullin once described the darkest side of his work as “a contamination of my mind that will never leave me”. His life in Somerset is a kind of exorcism of this mental pollution but it is as if he cannot quite believe his luck. He still seems to be looking over his shoulder from time to time, watching out for danger, wondering whether this life that he has worked so hard to create will all fall apart, and he’ll find himself back on the streets of north London, scrabbling for survival.

A retrospective of Don McCullin’s work is currently on show at Tate Britain in London till 06 May 2019. Admission is priced at £18 (Advance booking £16) / £17 Concessions (Advance booking £15) / £5 Family child 12-18 years www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullin

This interview was first published in the March 2010 issue of BJP.