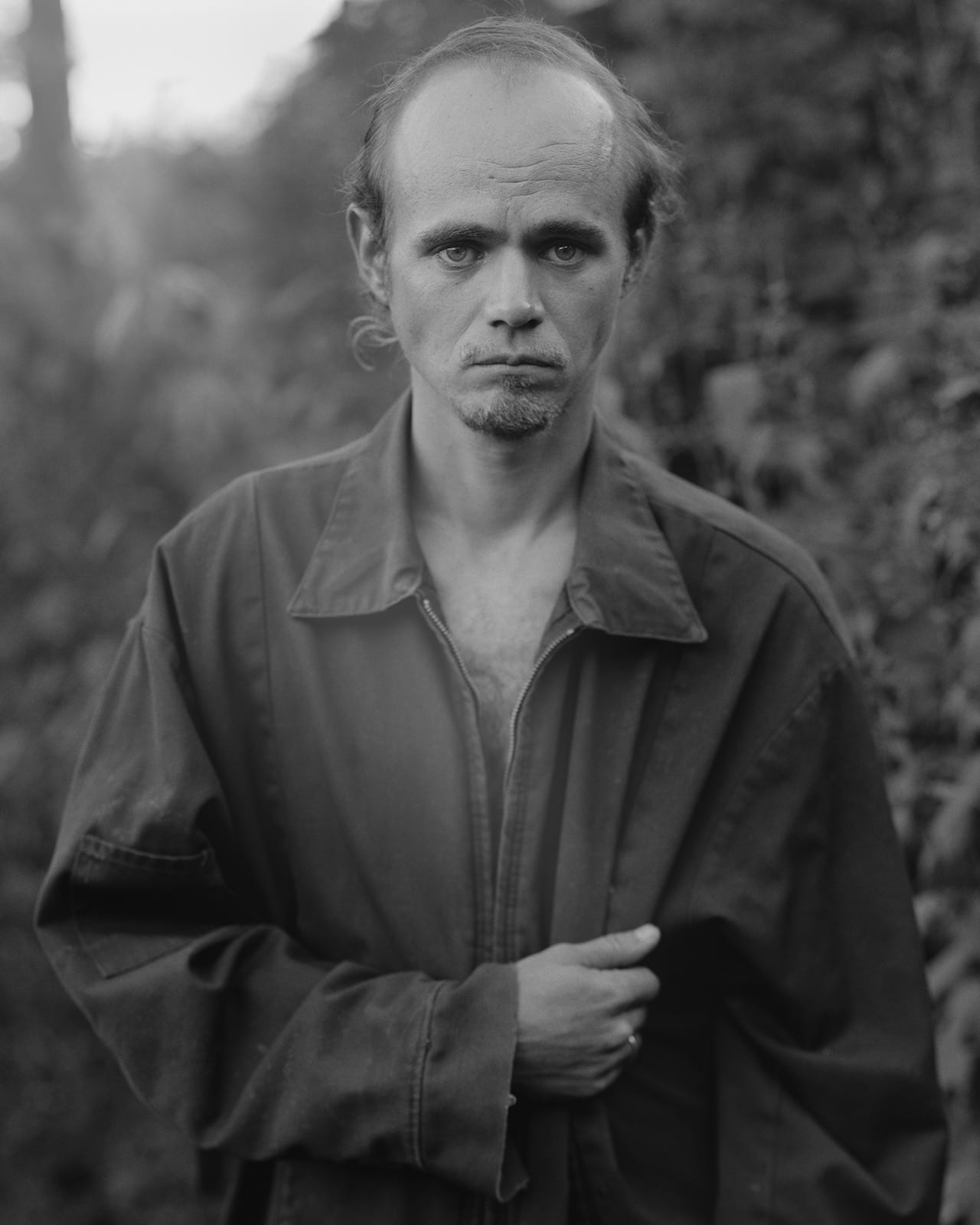

Photographed in the forests and mountains of the Ozarks, Matthew Genitempo’s first book, Jasper, published by Twin Palms, is a poetic exploration of the American landscape and the people who seek peace within its grasp, filled with an emotional range that is hard to pin down. Completed as his graduate thesis for an MFA at the University of Hartford in Connecticut, it’s the first major project he’s fully completed, and a gear shift towards leading from his gut.

“I was making photographs of the American Southwest, and Jasper [named after the town in Arkansas where many of the pictures were made] began when I abandoned all that work,” he says from his home in the west Texas town of Marfa. “I had been making photographs that were preconceived, but I wanted to make pictures that were leading with my eyes and my instincts.

“I started making photographs in this forest that was about 20 minutes south of Austin, called Lost Pines. I was photographing out there for two months, and then I started to go to other pine islands, and then to the Piney Woods region that feeds into the Ozarks. My initial goal was to break into new habits.”

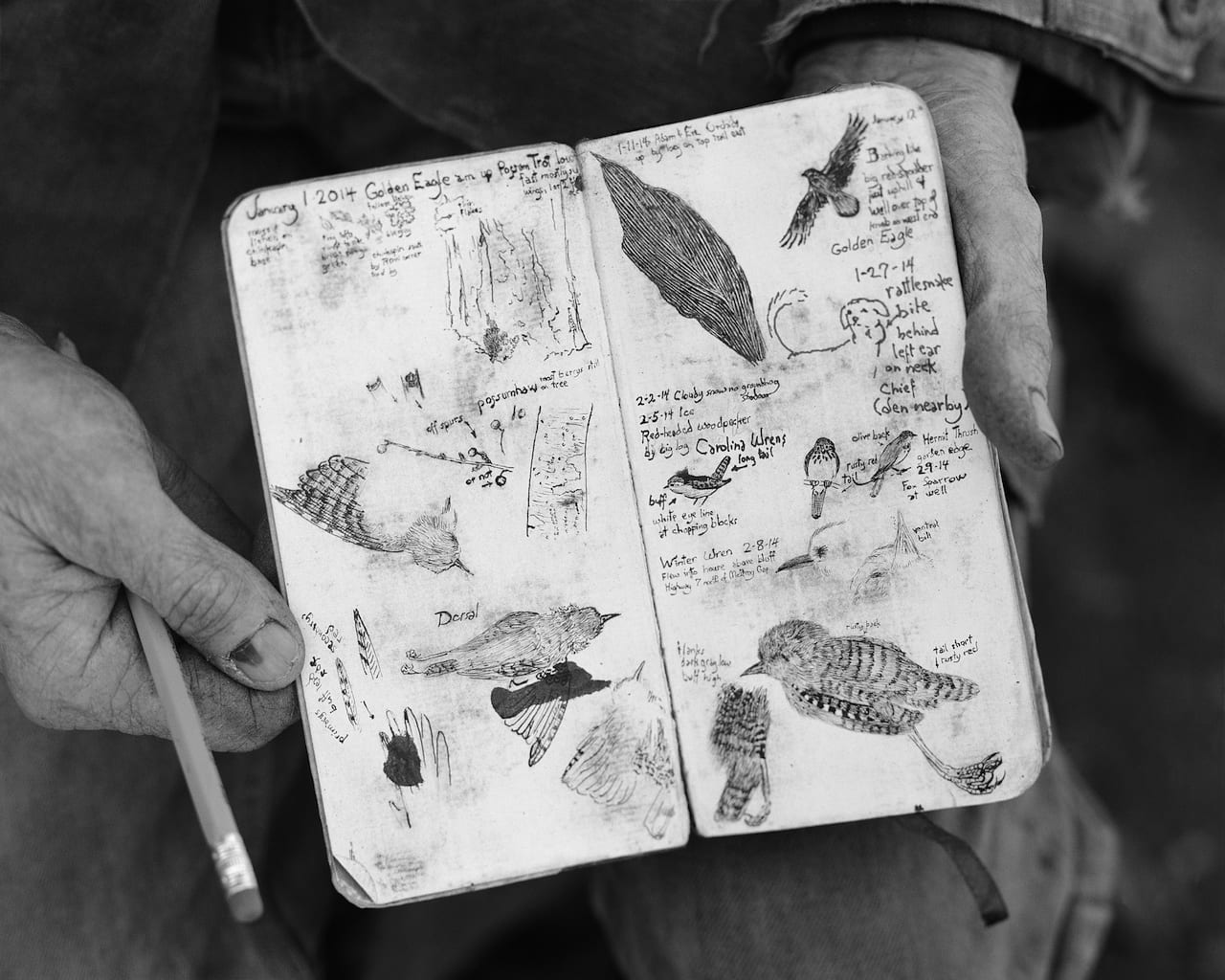

Led by intuition and a feeling for the landscape, Genitempo started looking at how poetry could provide a way of understanding himself, his images and the people and places he photographed. “I had this really obsessive fascination with the poet Frank Stanford,” he says. “He made all his work in the Ozarks, interweaving his own experiences and his own trials with this dream state, and I was really attracted to the success of that. I began to understand that when I arrived in the area – it was difficult to not experience the Ozarks through that lens.”

Stanford created poems rich in the imagery of land and death, filled with the random thoughts of the everyday. His poems are sensory, carnal and deeply Southern. “I started to make these instinctual pictures that had an internal necessity to them,” says Genitempo. “I didn’t really know what I was doing until I started noticing a pattern that began to emerge in those photographs.”

The pattern is one that has some echoes of Stanford’s poetry. Jasper is rooted in the landscapes of the Ozarks, environments that are layered with psychological, geographical and organic histories. They are landscapes that for all their wilderness like qualities, Genitempo imbues with a personality that merges with his photographs of the people who have sought escape in those woods. What that escape entails we are left to intuit from Genitempo’s poetic, caption-free sequencing. Nothing is spelled out.

“It’s definitely not a document of the Ozarks. I was exploring that area to explore a state of mind, to explore my fascination with running away. The work was made during the election of 2016 and the rise of Donald Trump, so I was really feeling that. There’s a great quote in my journal from that time from [US author] Chris Hedges: ‘The more we retreat from the culture at large, the more room we will have to carve out lives of meaning, the more we will be able to wall off the flood of illusions disseminated by mass culture, and the more we will retain sanity in an insane world. The goal will become the ability to endure’.”

Jasper is an escape then; from the world around you, from politics, from people, from the noise of the city, from the noise of your mind. At the same time, it’s a seeking of sanctuary in the wilderness of the Ozark Mountains, a quest for some kind of personal and psychological peace. “It’s almost like you have to go inward to escape, and that’s what Jasper is; it’s an exploration of that inward escape to examine your spirit,” says Genitempo. “It’s the same with photography. Photography is a thing when you can only use the outside world to describe what’s going on inside.”

There is minimal text in Jasper. You read the landscapes, the interiors of the lean-tos and shacks, and they feed into the images of the people portrayed in the book. It’s a lyrical back and forth between imagined psyches, imagined histories and imagined landscapes. There are no captions to pin things down, to render impotent the ambiguity of the images; the viewer is instead drawn into the resonances between one image and the next. The theme of escape, and the partner idea of the woods as a place of refuge, a place to escape to, is apparent throughout the book, but the danger here is of romanticising the landscape and the people living within it.

“That’s the thing I have to come to terms with,” says the 35-year-old. “The earlier photographs I took are a lot more romantic, a lot more idealistic, and the later photographs are more the reality of what living in the forest entails. There’s one photograph that captures that idea of the romantic side and the harsh reality – the photograph towards the end of the book of the man in the lean-to structure built against the side of a rock that encapsulates both the idealistic side and the reality.

“You’re presented with the idea of escape and building your own fort, and you see the man surrounded by belongings. It’s hard to look at, but I feel that dream – that fantasy – is still in that photograph.”

That image is preceded by a landscape which has a touch of the sublime, but also an organic heaviness that falls over the page into the rock lean-to picture, so that mortality is made apparent and things are clearly described both visually and emotionally. It’s a wordless description. Mark Steinmetz, Susan Lipper and Andrea Modica were influences for Genitempo, who wanted to avoid having an expository documentary style. So there are no biographical, geographical or personal details in the book.

“The thing is, people want answers. Who is this, what is that, where is this? But it doesn’t really add any value to the work. I’m not interested in books like that and never have been. What I was looking for with Jasper was to skirt that line between fiction and reality. I used a view camera, so there’s a lot of visual description in the book. I think of the Garry Winogrand quote: ‘There is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described.’ I knew I could still clearly evoke mystery in the photographs by clearly describing them.”

In Jasper, that mystery comes from the human relationship with the landscape. It’s a place to try and escape to and become part of. But the feeling in the book (and it is one of feelings, and stronger and more intelligent because of that) is that the land is not somewhere you escape to, it’s something you can escape from yourself in. There’s that immersive element to the work, where the land is not something we survey and control, but is something that we are part of.

“There’s always that potential hope of gaining enlightenment through a meaningful relationship with the natural world,” says Genitempo. “That’s something that everybody feels. That’s inherent to being human.”

matthewgenitempo.com Jasper is published by Twin Palms, priced $85 twinpalms.com