The Arctic Circle is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, for the past five years Arctic air temperatures have exceeded all records since 1900. If temperatures continue to rise, scientists expect that the North Pole will be ice-free in summer by 2040.

Ice reflects sunlight while water absorbs it, so less ice means even higher temperatures. But the consequences of disappearing sea ice in the Arctic are more complicated than the obvious impact it has on our global climate. Less ice provides new routes for maritime shipping, and opens up new areas for the exploitation of fossil fuels, transforming the region into a strategic battleground for countries with vested interests – not to mention indigenous villages whose livelihoods are threatened by rising sea levels.

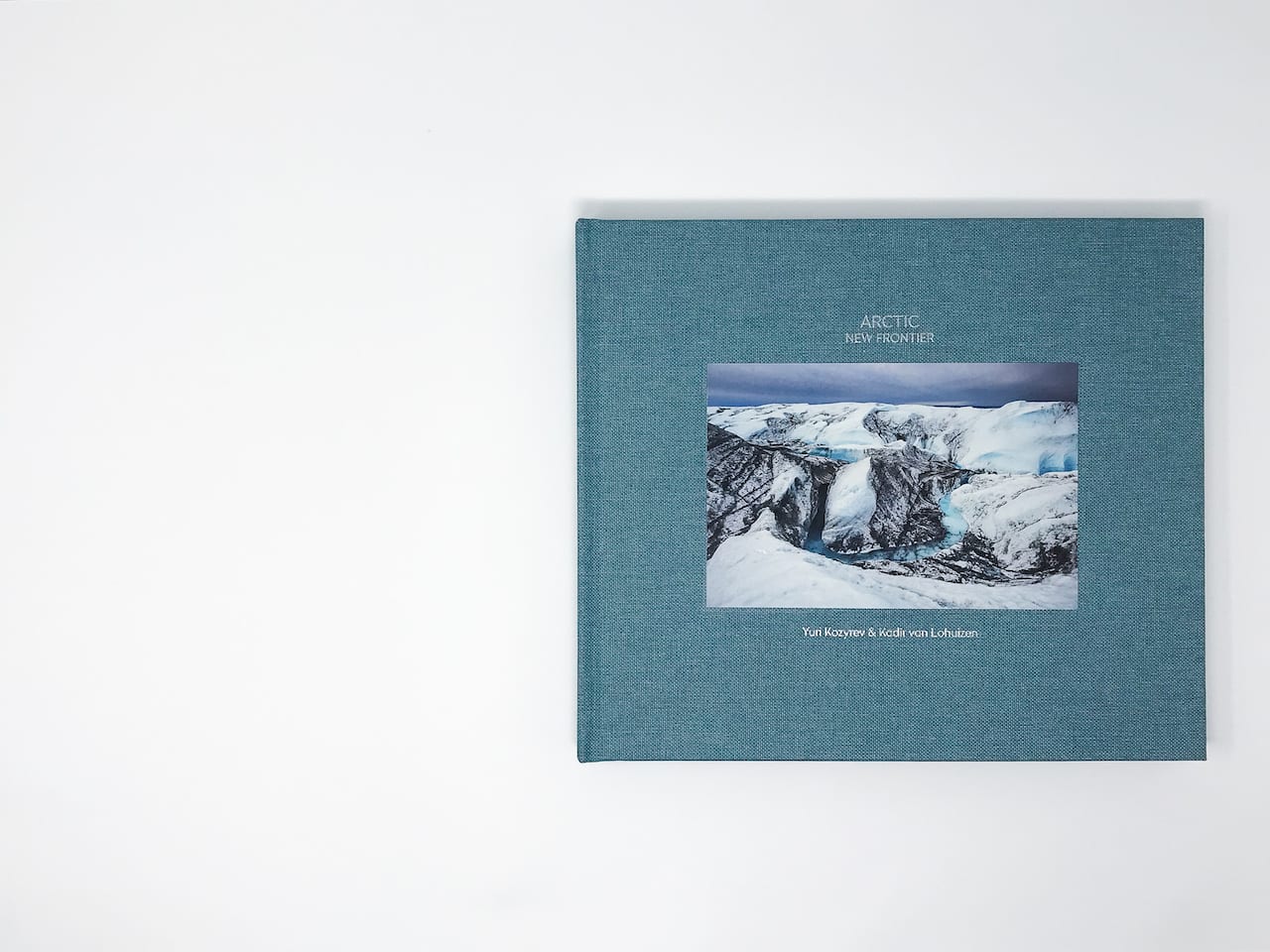

Photojournalists Yuri Kozyrev and Kadir van Lohuizen, who are both represented by NOOR, travelled through the Arctic Circle, documenting the startling, and often complicated, effects of Arctic climate change. Arctic: New Frontier is the product of the ninth edition of the Carmignac Photojournalism Award, which each year funds a new investigative photo reportage on a humanitarian and geopolitical issue. An exhibition of over 40 photographs and six videos will be displayed at London’s Saatchi Gallery from 15 March until 05 May.

Both photojournalists had visited the Arctic before, but travel there is expensive, making it very difficult to create coverage of this scale. “I don’t know any other media that would have assigned us to do this,” says Lohuizen, who is best-known for his coverage of conflict in Africa, and long-term projects on the seven rivers of the world and rising sea levels. Assuming each photographer would get better access closer to home, Lohuizen, who is Dutch, covered the Arctic regions of Norway, Greenland, Canada and Alaska. Kozyrev, who is Russian, covered areas in his home country. Together, the photographers travelled through over 15,000km of the Arctic circle.

For Kozyrev, who has covered international news for over two decades, “it was the right time to do something different”. He began his career documenting the collapse of the Soviet Union, before basing himself in Iraq for eight years from 2002, then covering the Arab Spring uprisings and their aftermath. Kozyrev wanted to move away from news and conflict, and felt he had found an important story. “I need to be just as committed to this as I was committed to the work in Iraq, that’s for sure,” he says. “It’s been a huge challenge to tell this story about climate change, it’s not easy.”

And money isn’t the only hurdle when working in the Arctic – travel options are limited, and as a journalist, access to ships, mines, and drilling facilities can be tricky. “The time we spent photographing was only a fraction of the time we spent on research and gaining permission,” says Lohuizen. On top of this, Arctic summers are short and late. In order to capture the visual effects of climate change in time for the book deadline, they had only a small window in which to make images.

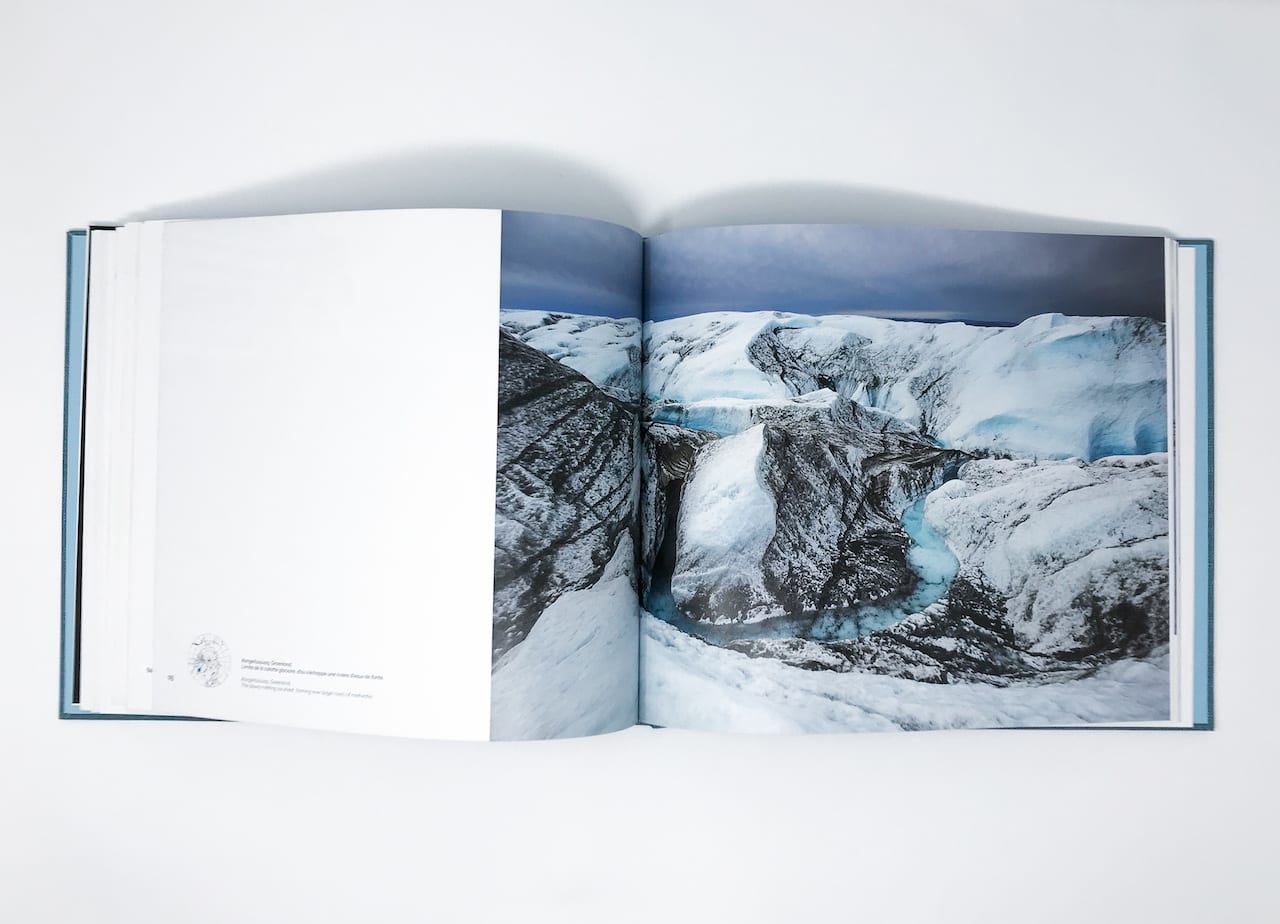

One of the most visible effects of Arctic climate change is the melting permafrost. In the summer months only the top few inches of ground thaws, before freezing again for winter. Beneath this thin layer is hundreds of feet of frozen soil and sediment called permafrost, which covers 25 percent of the northern hemisphere. In some places, it has been frozen for hundreds of thousands of years.

In Norilsk, Russia – home to the world’s largest mining and metallurgical complex, and one of the ten most polluted cities on the planet – Kozyrev photographed the remains of soviet Gulag barracks, which are appearing out of the ground due to the melting permafrost. Further north in the Verkhoyansky district, Kozyrev visited a crater the size of two stadiums, nicknamed “the door to the underworld” by locals. The hole, which continues to grow by up to 30m a year, is caused by soil compaction and ground collapses – a direct result of melting ice.

But vanishing permafrost doesn’t just affect the land that sits directly above it. Permafrost is one of the world’s largest stores of carbon, which in essence is cryogenically frozen within the soil. Scientists worry that if melted, this carbon could escape into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide or methane, accelerating climate change still further.

In both Kozyrev and Lohuizen’s photography, it is startling how much infrastructure has already been built within the Arctic Circle – especially in Russia, where there are factories, mines, roads, and small cities. One major reason why the Arctic has attracted global attention since the mid-2000s is the growing demand for fossil fuels. In 2009, the US Geological Survey estimated that 30% of the planet’s undiscovered natural gas and 13% of its undiscovered oil lies beneath the Arctic ice.

“People have a very romantic idea about the arctic, to do with polar bears and beautiful landscapes. But it’s often quite depressing, which might surprise people,” says Lohuizen, who saw first-hand the effects of offshore drilling on indigenous territory in Alaska. “It’s a pretty bleak picture,” he says.

Even though disappearing ice means easier access to reserves, drilling for oil comes with huge risks. No oil company has ever successfully cleaned up a major spill, let alone attempted to do so somewhere as remote as the Arctic. This is also a major concern with the growing Arctic tourism industry. In Norway, Lohuizen spoke to passengers of a 300-meter-long cruise ship capable of accommodating more than 3000 visitors. They had come to see “the last of the ice”, says Lohuizen, but the increasing demand for these tours is concerning in terms of both emissions and safety.

Still, there is a single positive effect of melting sea ice, which is the possibility for new shipping routes. Global warming is slowly opening up the Northwest Passage, just off the Canadian mainland. For companies transporting goods from Japan or China to Europe or the US, this passage could cut thousands of miles off journeys, with the possibility to reduce transport emissions by nearly half. Still, it is arresting to see Kozyrev’s photographs of mammoth icebreakers ploughing 50m-wide shipping lanes through meter-thick sheets of ice, and continuing disagreement between countries over access and sovereignty of the passage is likely to cause political tensions.

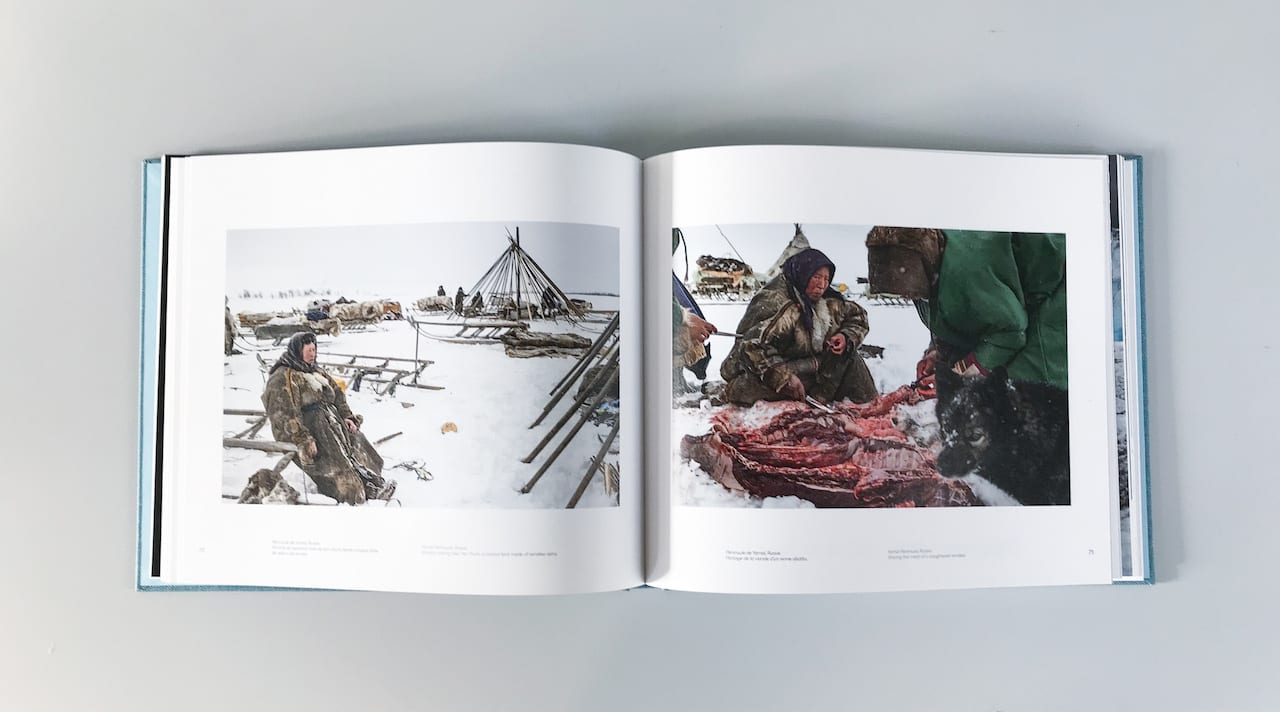

Arguably, the most troubling effect of climate change presented in Arctic: New Frontier, is its impact on indigenous communities, especially when we consider how much developed nations have contributed to global warming. In Russia, Kozyrev travelled with the Nenets, the last remaining Nomadic people of the Russian Arctic, who each year shepherd their reindeer more than 1000km across the Arctic tundra. In 2018, for the first time in history, their annual seasonal movement was interrupted, because of melting permafrost.

Similarly, in Point Hope in Alaska, melting ice poses a problem for the Inuit, an indigenous community who live off hunting bowhead whales – a tradition they have upheld for over 4000 years. Whale-hunting is an integral part of their nutritional and cultural values; the International Whaling Commission allows the Inuits to catch up to 10 whales a year. Lohuizen was with them during hunting season last May. The Inuits use cracks in the sea ice to track the whales as they come up for air. Less ice means the whales can swim around with more ease, which makes them harder to hunt, threatening the Inuits’ main means to survival.

“We all grew up with a white dot on the top and bottom of the world. Soon, there will be no white dots,” says Lohuizen. “If we look at it from a climate perspective, it’s very worrying.” The problem with the North Pole is that no country owns it, so there are no real regulations or laws to govern it. If we continue at our current rate, in two decades there may be no ice left on the North Pole. It will be open ocean.

www.fondationcarmignac.com Carmignac Photojournalism Award: ‘Arctic: New Frontier’ by Yuri Kozyrev and Kadir van Lohuizen will be on show at the Saatchi Gallery in London from 15 March till 05 May 2019 www.saatchigallery.com