In the morning of 04 June 1989, photojournalist Liu Heung Shing received word that the Chinese military had opened fire on protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. After two months of hunger strikes sparked by the death of Hu Yaobang, a former Communist leader who was seen as a champion for liberalisation, the city was under martial law, and the government made a call to quell the rebellion by bloodshed.

Knowing the tanks were heading in his direction, Liu scrambled into his car and drove to the legation quarter, racing up to a nearby rooftop to gain a better view. Rows of military tanks were parading east, and beneath them he spotted a young couple on a bicycle, hiding under the bridge. ‘There was another story to be told there,” says Liu, “a human story.”

This is the approach that would later set Liu’s images apart from other photographers who documented China in the 20th century. Rather than capturing the visual motifs of communism, Liu was more interested in the impact of politics on the everyday lives of Chinese people. Beginning in the aftermath of the death of Mao Zhedong, Liu documented the rapid transformation of the country, from a collectivist state to an individual, capitalist society.

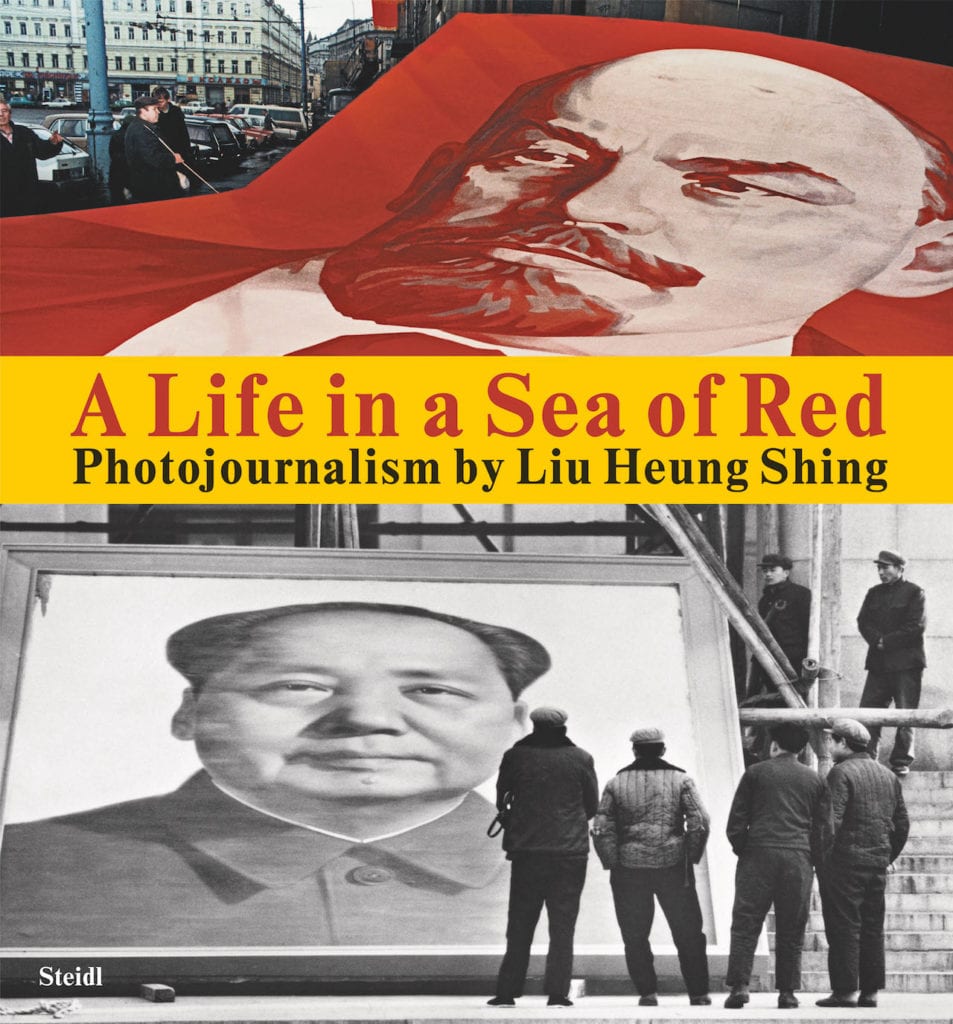

This year not only marks 30 years since the Tiananmen Square massacre, but also 70 years since the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, and century since the anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement in 1919. Liu’s new book, A Life in a Sea of Red, presents two of his most important bodies of work from China and Russia, captured during four pivotal decades for communism, from the death of Mao in 1976, to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and his most recent portraits of figures in contemporary Chinese culture.

Beginnings

Liu was born in Hong Kong in 1951, but was educated on the mainland between the ages of three and nine, before returning to Hong Kong, and then to New York to study politics and journalism.

There are a number of elements about Liu’s upbringing that would eventually lead to his career in photojournalism. Firstly, he studied under three systems of education: in China, Hong Kong – which was modelled on British education during colonial rule – and the US. “These experiences gave me an early start to understanding how different China was to the rest of the world,” he says.

The photographer’s scent for news was also sparked during his teenage years. His father was the editor of a progressive leftist newspaper, and so he spent many summers helping to translate Reuters news stories.

But photographically, his biggest influences came during his final year at university, where he enrolled in a photography class with Gjon Mili, the image-maker known for his portraits of Pablo Picasso painting with light.

“He opened my eyes,” says Liu, explaining how he was taught the distinctions between photography and other forms of art. “I learned that photographers can capture a moment in ways that painters, sculptors and writers could not.”

In 1975, Liu was invited to intern for Mili on the 28th floor of the Time-Life Building in New York. It was there that he spent hours rooting through the Time-Life picture archive, studying photographs of China by some of Life magazine’s greats, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Marc Riboud, and Dmitri Kessel, among others.

“Seeing their perspective and understanding of the country was helpful for me,” he reflects, “but I felt that they came to photograph China from a little bit of a sympathetic point of view.”

Recognising that it was harder for foreign photographers to get inside the system and its people, Liu saw an opportunity. “I realised I could use my camera to do political reporting in China, like what the writers were doing. A photograph can observe and capture so much of how politics intervenes in people’s daily lives.”

Post-Mao China and the Tiananmen Massacre

When Mao Zedong died on 09 September 1976, aged 82, Liu secured an assignment with TIME, and travelled to China to document the aftermath of the leader’s death.

At the time, there were only a few Western news outlets with Chinese bureaus, so as a Chinese speaker with a Hong Kong passport, Liu had a greater advantage over other foreign journalists. He flew from Paris to Hong Kong, and he managed to board a train to Guangzhou, where he photographed civilians wearing black armbands to mourn the death of Mao. Though he did not achieve his goal of travelling to Beijing to photograph Mao’s funeral, these first images led him onto a trajectory he would follow throughout his career.

In the following years, Liu photographed all over China, making images that captured daily life at schools, local food markets, theatres and on farms. He also photographed the formation of the Democracy Wall in Beijing, where thousands of people posted protests about social and political issues, as well as the march for freedom in the Arts in 1979.

Liu was able to access, observe and capture subtle moments that would later become significant. He saw the importance of documenting the first Coca Cola in China, new advertisements for Sony products, and peasants tossing a harvest of cabbages – the only vegetable available to Northern Chinese in winter – onto a slow moving truck.

These are all images that track a country on the brink of rapid economic and social reform. Under the new leadership of Deng Xiaoping, communist China was transformed beyond recognition into the economic powerhouse that it is known as today – “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. “Many photographers didn’t understand the process and the history behind that speed,” says Liu, “it was not obvious to them where to look.”.

After publishing his landmark book in 1983, China After Mao, which received a review in Newsweek that hailed Liu “the Cartier-Bresson of China,” the photographer gained recognition from the Associated Press, and was posted in California, India, and Korea.

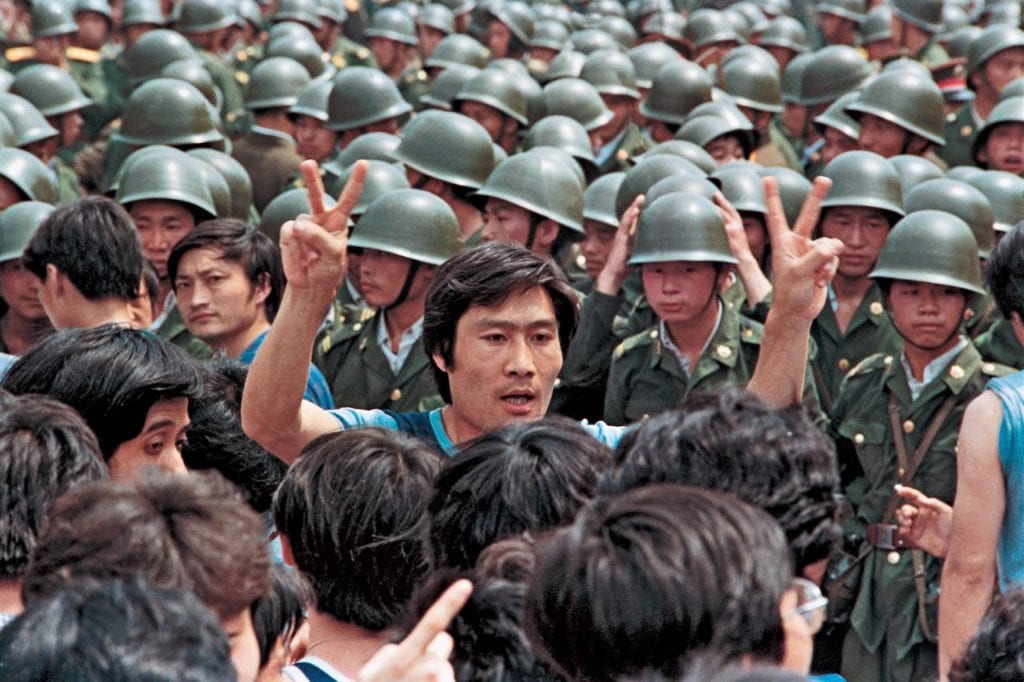

During his time covering the uprisings in Seoul, where he documented student protesters hurling stones at Police, who in turn responded with swarms of tear gas, news broke about the students who were occupying Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

In mid-May 1989, Liu was sent to Beijing to cover the protests, by which time many foreign journalists were leaving, assuming the protests would soon start dwindling. On 30 May, a group of students transported a 10-metre-tall styrofoam structure, the Goddess of Democracy, placing it in the middle of the square to face the portrait of Mao.

“This did not go down well with the communists,” says Liu. “Looking back on those photographs before 04 June, you can feel the tension. To me, the statue was like an omen.”

Four days later, armed troops entered the square, where gunshots were heard for the following two days. Exact death tolls have never been released, but estimates range from hundreds to tens-of-thousands.

“When you look back, it brings back memories,” says Liu, about the process of making A Life in a Sea of Red. None of Liu’s images have ever been officially published in China, bar one photograph from Tiananmen that was accidentally printed in the Beijing News. By midday the issue was pulled from newsstands, and the duty editor in charge of the issue was demoted.. In China, all mentions of the protests are still censored, with all traces of the massacre is omitted from the press, education, and online communication.

Two days ago, in a rare acknowledgement of events, China’s defence minister defended the crackdown on Tiananmen Square as the “correct policy”. The fight for justice is far from over, but after four decades of reporting, Liu, now 68, spends most of his time working for the Shanghai Centre of Photography, which he founded in 2015. He also continues to make portraits of figures in Contemporary Chinese culture, some of which are included in the book,

“Documenting the transformation of China has been really quite an experience. I’m grateful to have had that opportunity,” says Liu. But, he says, “China’s story is far from over – it’s still happening.”

A Life in a Sea of Red is published by Steidl.