This article was originally published in issue #7893 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

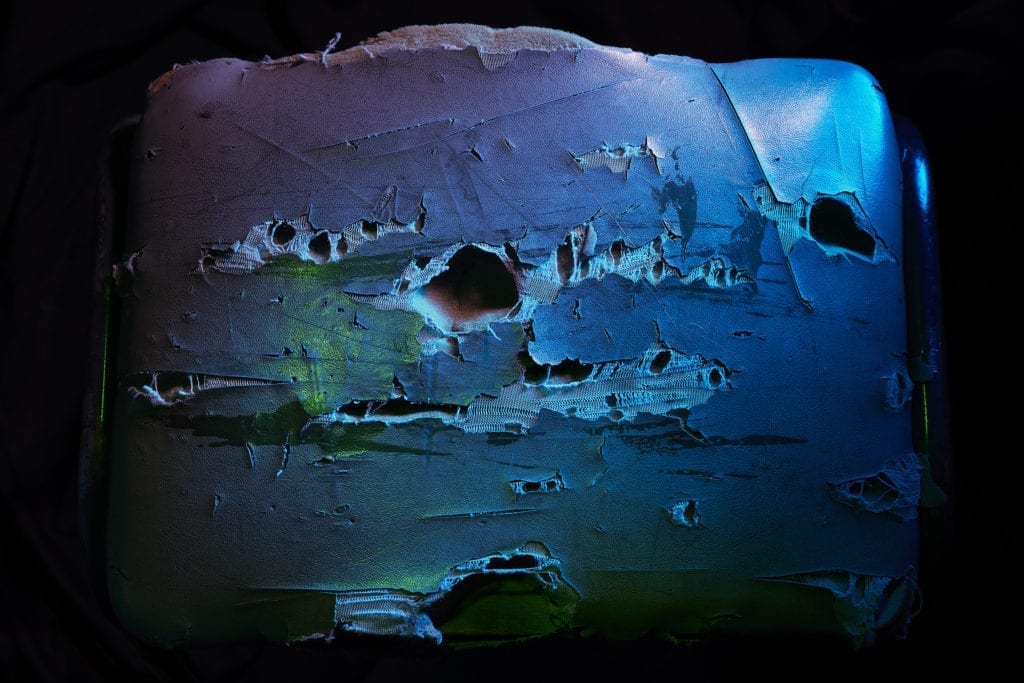

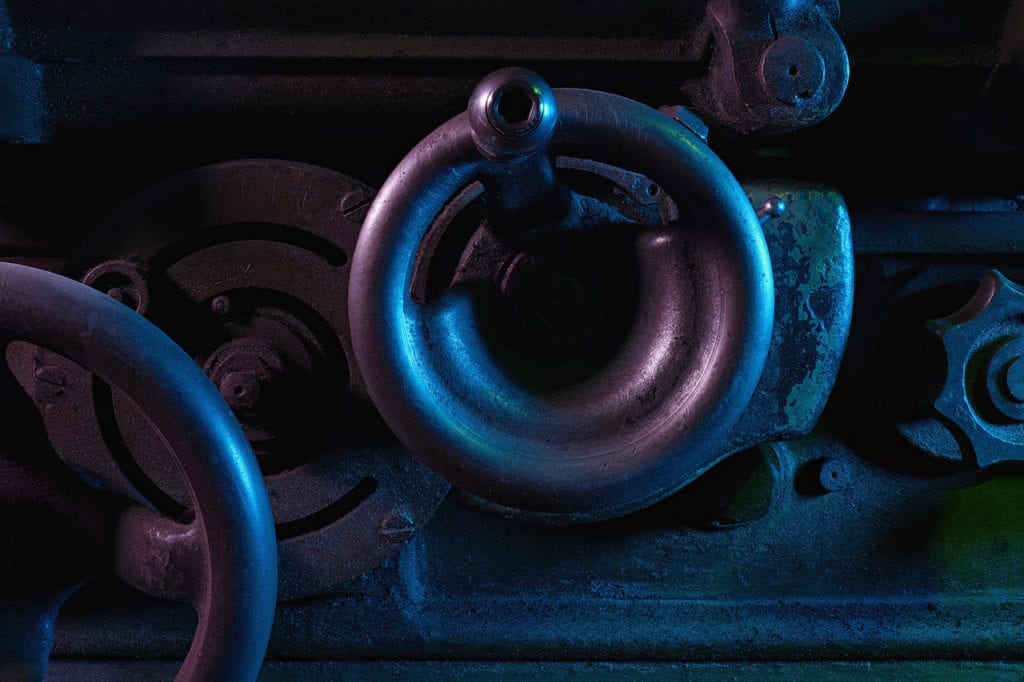

A single image epitomises Theo Deproost’s approach in his latest project, Still Works, depicting the empty silhouettes of knives surrounded by coloured light. The picture comprises part of a series created in knife-maker Stuart Mitchell’s workshop, but the results of his labour are invisible throughout. Instead the series consists of surreal still lifes that monumentalise the studio’s machinery and the materials of Mitchell’s trade: tangles of wiry metal shavings explode from a container; the rugged surface of a stool is covered in slashes and rips.

“I am drawn to the details and the things that you would often pass by,” explains Deproost. The photographer met Mitchell two-and-a-half years prior to making the work, while assisting on another shoot, and Portland Works in Sheffield, in which Mitchell’s workshop sits, enthralled him.

One of the only remaining operative metal trades factories in the UK, it opened in 1879 at the height of steel manufacturing in the city. To begin with, the factory housed the workshops of the many tradesmen involved in the cutlery industry; today, a variety of craftspeople inhabit it. Deproost was fascinated by this history of the factory, and that of Mitchell’s workshop, which originally belonged to his parents, who relocated their family business, Pat Mitchell Cutlers, to Portland Works in 1980.

Stuart Mitchell Knives continues there today, one of the few remaining artisan metalworkers in a city that has been renowned for its cutlery for more than 700 years. “It is like being dropped 140 years back in time,” says Deproost who, on returning to the workshop, decided it was the aged environment on which he wanted to focus, drawn to the physical signs of wear that have gradually engulfed it.

“It was a way of avoiding being too literal,” continues Deproost, whose images capture the history of the place, while simultaneously transforming the objects within it. The photographs appear futuristic: the shots’ close-up angles abstracting their subject matter, which Deproost bathes in neon light.

“All the objects are broken down using blue, green and pink, or blue, green and orange,” he explains, “which allows me to illuminate different details.” The photographer has a background in still life and produced each image as though he was working in a studio, building up the compositions with carefully positioned lights – “moving things by degrees and knowing when it felt right”.

Mitchell’s disposition is also materialised in the subjects captured. “They say something about him; that he has chosen to keep these objects rather than replacing them,” says the photographer, referencing the lacerated covering of Mitchell’s stool. The rich backstory is central to the series, which Deproost is adamant should ground the visually surreal work.

But the ambiguity is also important, making for images that force us to contemplate what is shown – imbuing a straightforward subject with a sense of intrigue and the unknown: “It transforms something that could seem everyday, which people might pass by and ignore; the work transcends that and creates something that people will have not seen before.”

—