This article was originally published in issue #7893 of British Journal of Photography. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

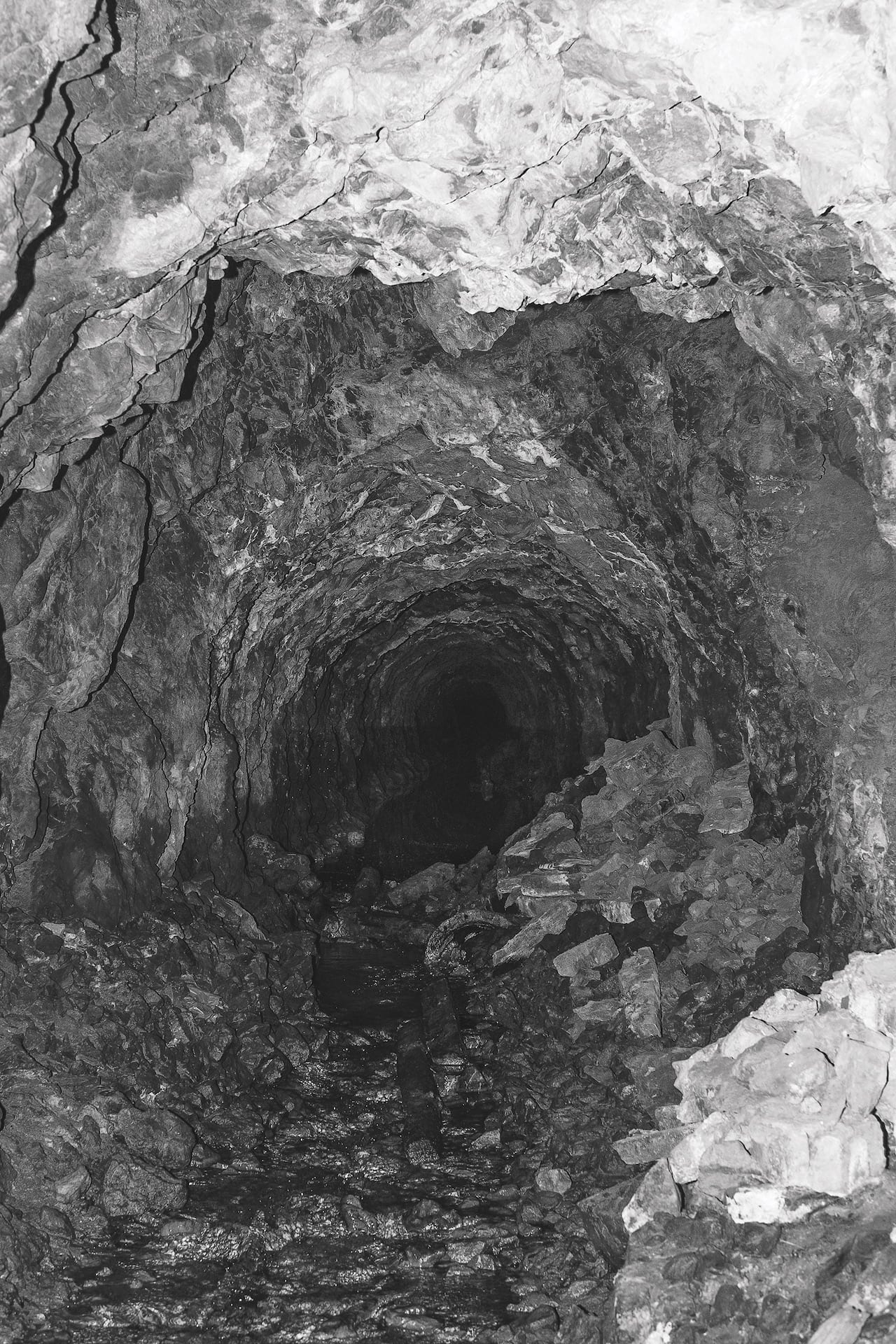

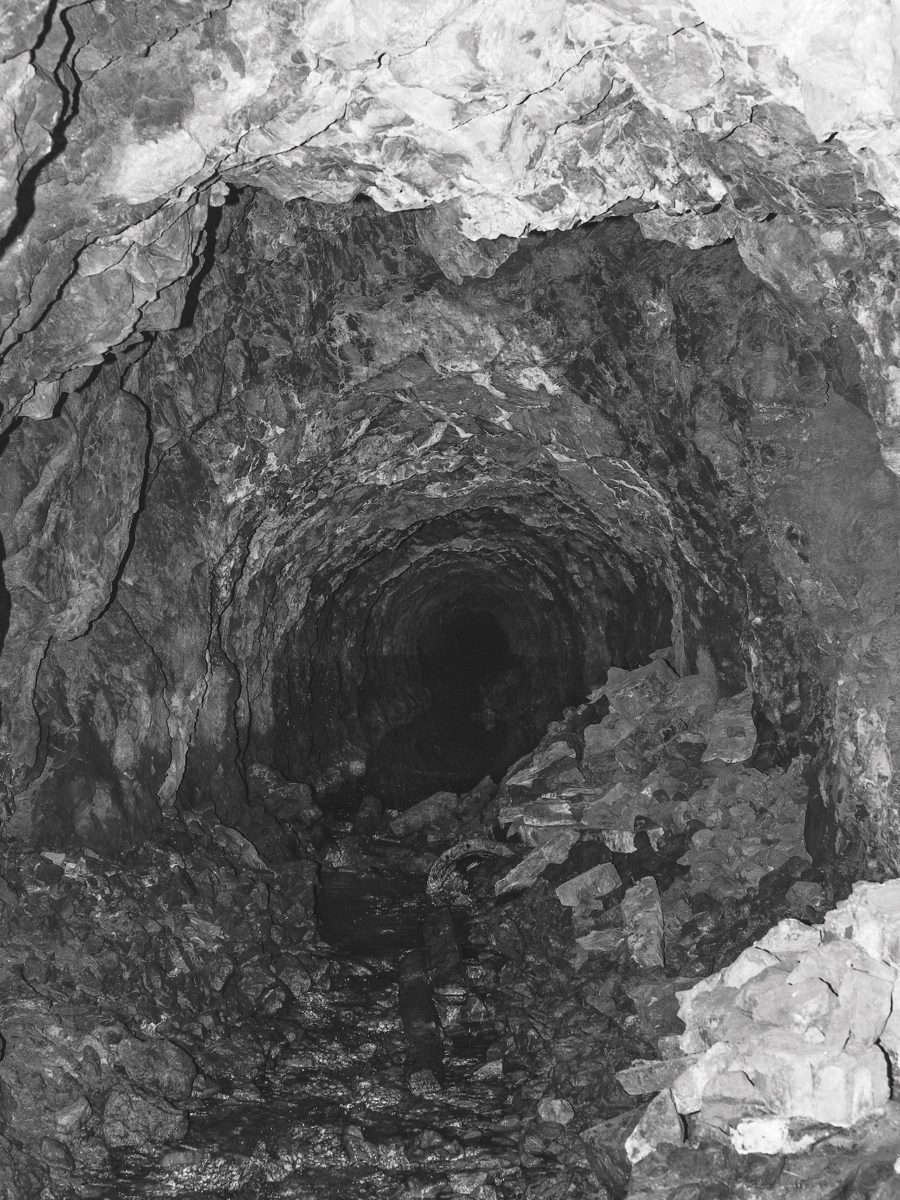

There’s an absence at the core of Silent Canary, a project by the Netherlands- based Italian photographer Filippo Maria Ciriani. It depicts the Belgian town of Kelmis, a place whose raison d’etre has ceased to exist. Straddling the present-day Dutch and German borders, between 1816 and 1920 it was the core of a microstate called Neutral Moresnet. Kelmis lies atop one of the largest zinc spar deposits in Europe. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, it was parcelled off into a shared dominion by, first the Netherlands and Prussia, then Belgium and the German Empire.

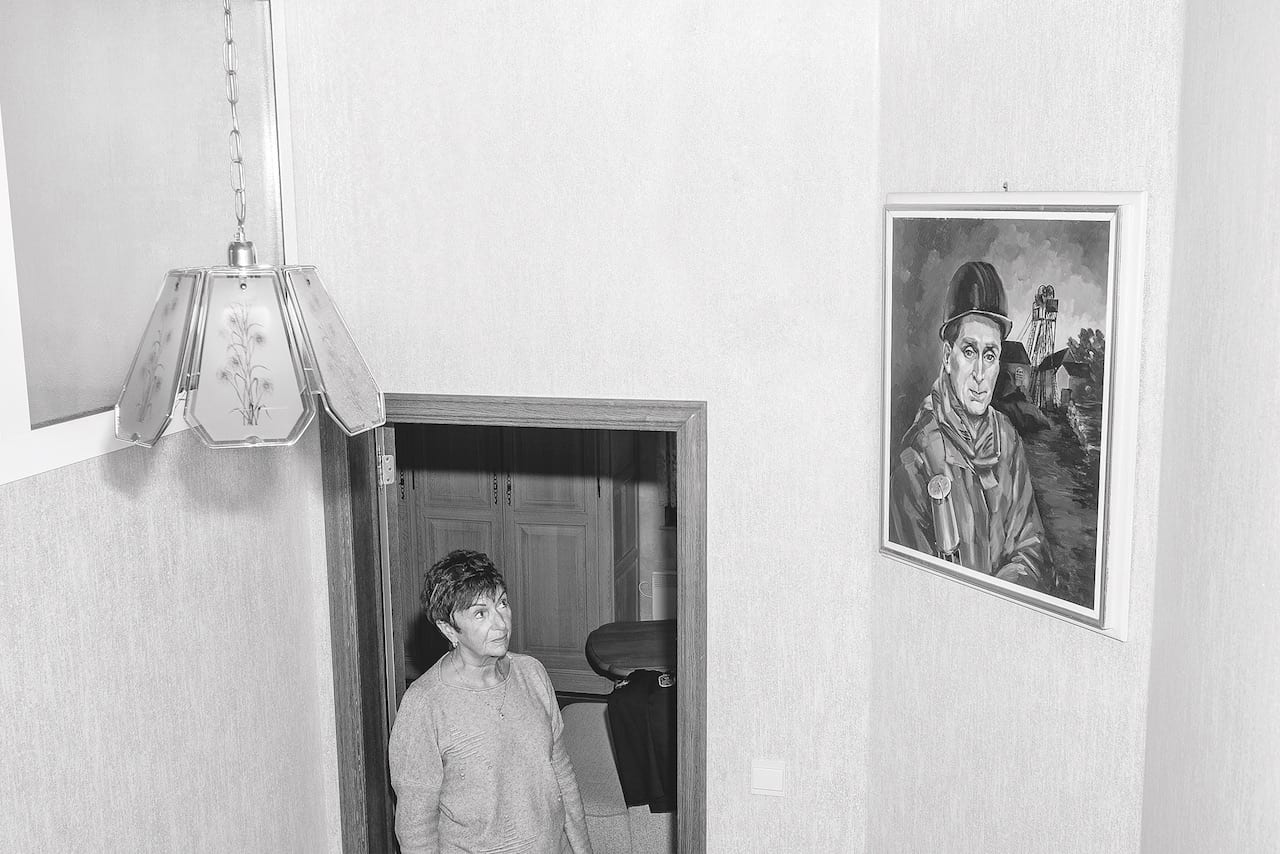

Effectively governed and developed by the Vieille Montagne mining company, Neutral Moresnet flourished, and its population boomed. “The company shaped the landscape and its needs,” explains Ciriani. “They built streets and houses, giving the initial structure of the city. And they founded several clubs that still exist, such as a choir and a shooting club.” Residents were officially stateless. He adds, “What does it mean to be a citizen of an artificial country, a place where a company is in charge?” The mine closed in 1885, and Neutral Moresnet lost its purpose, eventually becoming absorbed into Belgium in the aftermath of the First World War.

Ciriani came across the story in 2018, while rambling up the Vaalserberg, a large hill that stands at the tripoint between Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. “I wasn’t homesick,” recounts Ciriani, who grew up in Italy’s Alpine north-east, “but I wanted to get close to something familiar. There is nothing more so to me than walking up mountains.” He chanced upon an information board expounding the history of Neutral Moresnet, and his interest was piqued.