Alzheimer’s is a form of dementia, which results in the slow decline of brain function: memory progressively deteriorates until the sufferer loses touch with reality and control over bodily functions. Over five years, from 2014 to 2019, Anne Moffat charted the slow descent of her maternal grandmother Kong Fung Tsze (1928-2019) into the disease. Over several trips from Australia, where Moffat grew up and currently lives, to her grandmother’s home in Sandakan, Malaysia, she embarked on “a process of trying to understand more of who I am and who she is, while watching her lose her independence and sense of self”.

The resulting project Forget Me Not / 勿忘我 is multi-layered: melancholic and nostalgic, but also replete with colour and life — a homage to Tsze’s final years peppered with references to her life, her culture, and the disease. “Goldfish are stereotypically considered to have a short memory span,” says Moffat, referencing an image of the luminescent orange creatures lurking in the corner of their tank. “Watching the fish circle in their tank, I couldn’t help but think of jia poh [translating to maternal grandmother] confined within her mind, endlessly circling, peering out but unable to communicate. When I returned, years later, the goldfish were gone, replaced by tiny guppies.”

“Goldfish are stereotypically considered to have a short memory span. Watching the fish circle in their tank, I couldn’t help but think of jia poh [translating to maternal grandmother] confined within her mind, endlessly circling, peering out but unable to communicate”

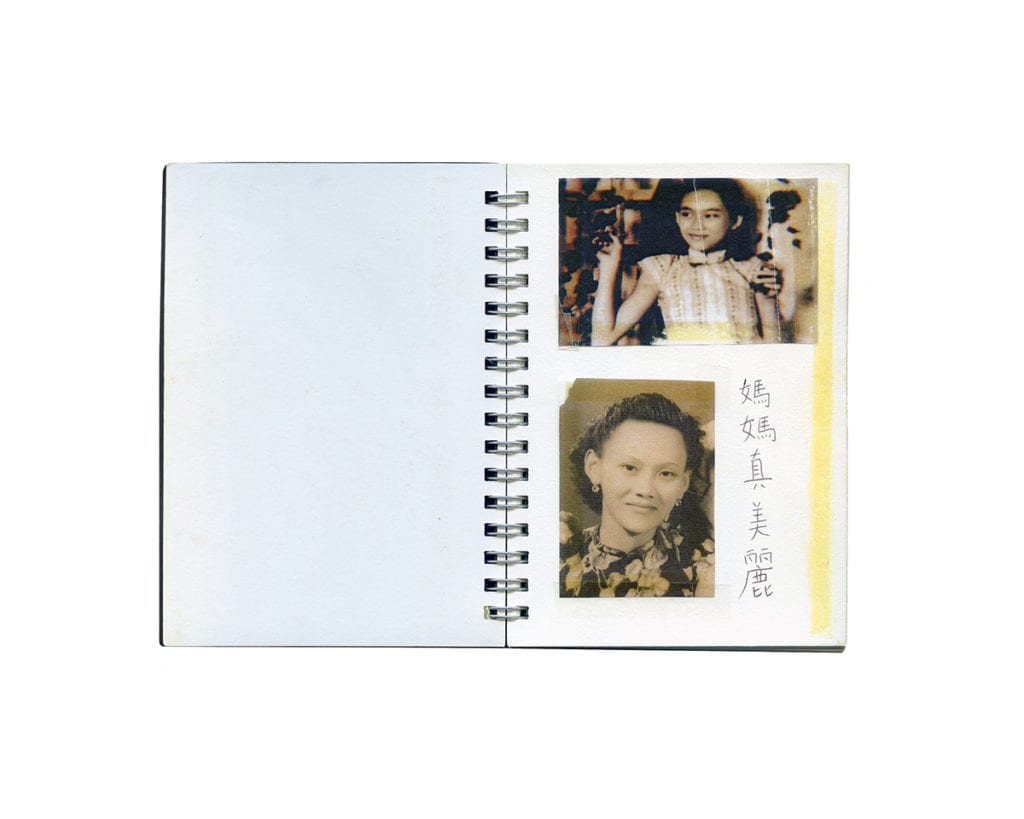

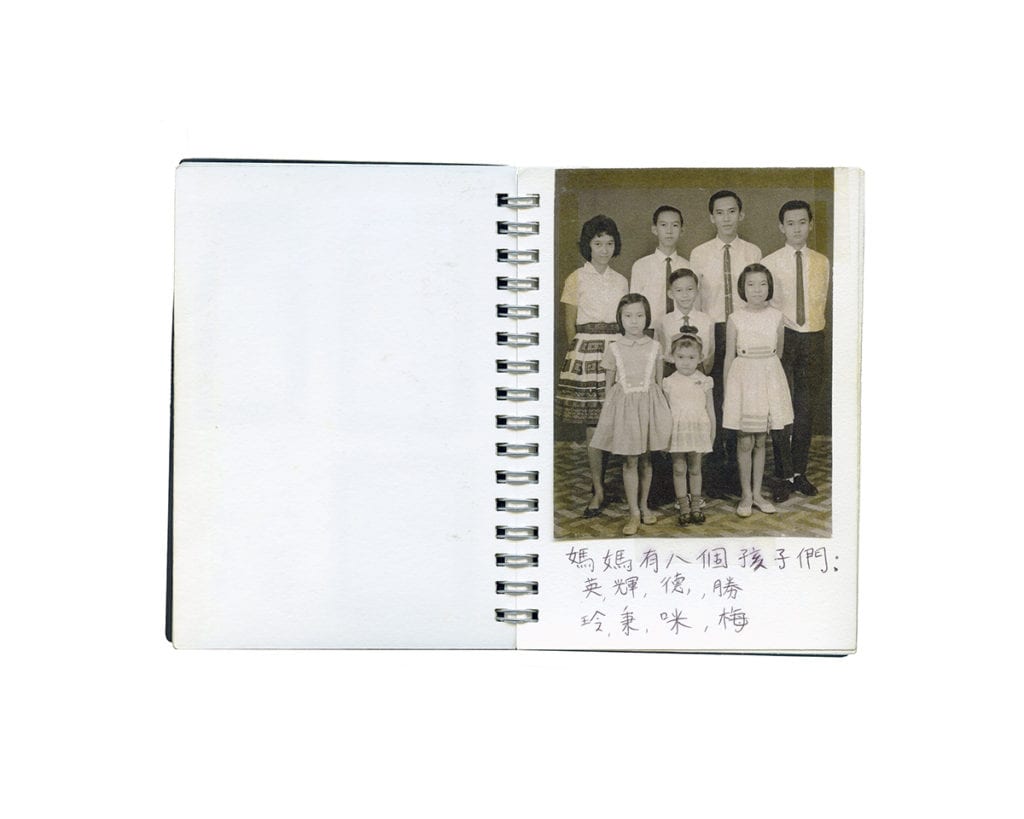

Tsze’s life was long and rich. At 90-years-old, she was a mother to eight, grandmother to 18, and great-grandmother to 10. Moffat’s series captures her cosseted at home surrounded by family. Interspersed among these vivid images are pages from several “life story” notebooks. “When my grandmother first started forgetting, my mother crafted her several small notebooks lovingly filled with images and handwritten memories of their lives together,” explains Moffat. “Ironically and brutally, the more you read your life story, the further along the path of dementia you are, and the less you recognise it as your own.”

Below, Moffat reflects on documenting her grandmother’s disease, and the experience of making such a personal project.

—

Can you tell me about your grandmother and your relationship with her?

My jia poh 家婆 (maternal grandmother) Kong Fung Tsze 江鳳慈 was born in 1928, the Year of the Dragon, in Sabah, Malaysia. Mother to eight, grandmother to 18, great-grandmother to 11 and counting — her presence was pure, calm magic; her love transcended language and distance. As our lucky dragon and gentle (慈) phoenix (鳳) she truly epitomised both her zodiac and her name. A talented chef, craftsperson, dressmaker and gardener, she could turn anything into a masterpiece. Her quick wit and joyful spirit brightened our lives.

While my grandmother lived in Sandakan, Malaysia, I grew up in Australia. I have many fond memories of family visits to Malaysia and my grandparents’ visits to Australia over the years. I have not mastered her mother tongue of Hakka, Chinese and she didn’t speak much English, but this somehow added to her wisdom, humour, and enchanting nature.

Can you explain the experience of documenting her descent into Alzheimer’s? What was it like visiting and photographing her on several different trips?

They call Alzheimer’s “the long goodbye” and it’s true — it’s a painfully gradual loss. My grandmother’s personality was slowly worn away, along with her cognitive skills and memory. She put on a brave front with incredible strength and patience even when she realised that her mind was failing. Near the end, she couldn’t speak, eat or move, and she needed full-time assistance with every aspect of daily life.

Visiting sometimes left me feeling helpless. Each visit was a discrete point in a continuous decline of health. There was nothing anyone could do to stop things progressing further. From a photography perspective, it’s always difficult to know whether to scramble to record a moment or to put the camera down and be fully present, but this feeling was exacerbated hundredfold because it was clear each moment would never recur again.

Even through the most difficult periods, each time there were visitors, especially her grandchildren, jia poh’s face would light up — she would hold our hands and pat our shoulders even if she didn’t know who we were. It became more and more heartbreaking to leave her as the years passed. Each time I hugged her goodbye I wasn’t sure whether it would be the last.

“From a photography perspective, it’s always difficult to know whether to scramble to record a moment or to put the camera down and be fully present, but this feeling was exacerbated hundredfold because it was clear each moment would never recur again”

What were you looking to express through your images — did you have specific ideas in mind, or did the various images evolve organically?

For personal projects, things usually unfold before me, and I know what I want to capture only once I see it. I didn’t set out to document my grandmother in particular or her decline in health. I think I began this series for the joy of recording moments with family, and to understand more about my connection with my mother and grandmother’s homeland. Only years later could I really start to piece together this story, and understand what I had been trying to capture all along.

The project feels full of colour and life despite its melancholy subject-matter. Was this intentional, and if so why?

When I think of Malaysia, I picture the wonderful mix of garish and faded colours that can be seen everywhere from the plastic restaurant chairs and tableware to my grandmother’s wardrobe of vibrantly patterned shirts and batik materials.

Each visit back was both heartbreaking and heartwarming — my grandmother was slowly fading, but there were relatives to see, delicious meals to eat, markets and rainforests to visit — and as much as you don’t want it to, life goes on. I am grateful to my uncles, aunties and cousins in Malaysia who always looked after us really well during each visit. With each trip, I gained a new understanding of my family’s homeland, while at the same time losing an integral part of this connection.

Why did you decide to include excerpts from the ‘life story’ notebooks alongside the images?

Alzheimer’s Disease tragically and unfairly strips its sufferer of all memory and context. I didn’t want to do the same to my grandmother in my portrayal of her life. It was important to me that if I was going to share her suffering, I would also provide glimpses into the vibrant and full life she had once lived — the memories she had held tight and ultimately lost.

Jia poh had looked through these books in an attempt to remember, and as a way of passing the time. The double-sided tape that mum had used to stick the photos in had yellowed and bled through each page — I found this oddly beautiful, paired with my mum’s handwritten messages of encouragement.

Although it is a cheap notebook with laser printed images, the pages hold great value to me. Ironically and brutally, the more you read your life story, the further along the path of dementia you are, and the less you recognise it as your own.

How did you endeavour to communicate the period following your grandmother’s passing through your images?

For those suffering from Alzheimer’s, they have often left long before their bodies fail. This bright person, full of life, fades gradually before your eyes. A few people have commented that for a series about my grandmother, a lot of the scenes are quite still and devoid of people — and perhaps this stems from the feeling that we had already lost her years earlier, and were either anticipating or already dealing with our grief. This ambiguous loss plays throughout the work, as it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact moment Alzheimer’s takes a life. My understanding of my grandmother’s passing is still evolving every day; I’m still living it. But I know I’ll forever remember and carry her wherever I go.

See the series in full and more of Anne Moffat’s work here.